By Tina Engels

A couple of summer’s ago Tina Engels and I had the great pleasure of meeting and interviewing Dan Gustin in his incredible home and studio in Italy. A number of delays prevented us from finishing and publishing this wonderful interview that Tina Engels wrote until now. I would like to thank Dan Gustin and Tina Engels both for their time and energy in putting together this insightful look at his background, process and thoughts on painting. – Larry Groff

Dan Gustin has been a Associate Professor of Art (tenured) at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago since 1984. He has been a visiting artist for many years at the International School of Art in Umbria Italy. He received his M.F.A. at the Yale University in 1974 and his B.F.A. at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1972. He has had numerous solo shows at the ISA Gallery, Umbria, Italy, Geschiedle Gallery, J. Rosenthal Gallery, and the Lyons Weir Packer Gallery in Chicago, Forum Gallery in NYC and Alpha Gallery in Boston, the Paul Mellon Arts Center, and the Rockford Art Museum. and many others. He has shown in over fifty group exhibitions throughout the United States.

Gustin’s work is in the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington D.C., Art Institute of Chicago, The Huntington Museum of Art, West Virginia, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA and in private collections in New York and Chicago. Mr. Gustin is a recipient of the Purchase Award at the annual Arts & Letters Show in NYC and is a member of the National Academy of Design. He has also won grants from the Illinois Arts Council, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago Faculty Enrichment Grants and the National Endowment for the Arts.

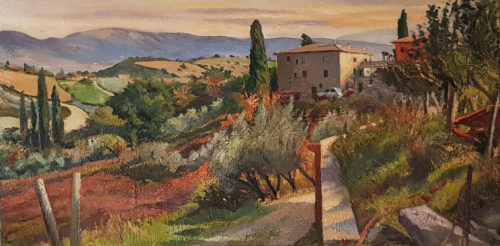

Dan Sheridan Gustin spends his summers painting and teaching near his home in Umbria, Italy. While there Gustin paints the landscape often working on three or four paintings a day. During the rest of the year Gustin is an associate professor of art at the Art Institute of Chicago. While home in Chicago the artist focuses on his large scale narratives.

William Bailey wrote about Dan Gustin and Langdon Quin in September 2017: “…Each has found challenge and meaning in this Landscape so often painted throughout history. They bring their own histories, as did Claude and Corot in their time. They paint with conviction and imagination, shunning the mannerisms which conventionally assure contemporaneity. Gustin and Quin share a subject but find completely different content….Dan Gustin’s landscapes are typically large-scale, and executed entirely within the setting portrayed in his paintings. Using a full range of vigorously applied color and tone, he fills his canvases with the space, light and atmosphere which characterize each particular place. Gustin’s painterly presence and mastery are his own, but one can sense the extravagant Courbet lurking nearby – urging him on.”- William Bailey

Larry Groff: Please tell us how you came to be to Italy?

Dan Gustin: Initially I was hired by Helaine Trietman, Mark Servin and Nick Carone to teach at the International School in Italy during the summer. The first month I was there, I just stayed in my room and could not paint. I had never painted landscape and I had no ideas or desire to do it. I thought I had to paint large narrative paintings here and I just couldn’t. I was depressed and completely blocked. I didn’t know what to do. One day I just kind of peeked out and started doodling away. One thing led to another and I was soon out in the landscape and totally fell in love with the place.

I think people who paint landscapes are looking for a home. I know I was. I found my painting home was here in Italy. The light the spaces, the land and sky all became familiar in some strange way and it was what I wanted to paint about. Then I had to do hundreds of terrible paintings. But, everyday I am here I learn more.

Tina: You certainly found the perfect place to do this work. These enormous vistas appear cinematic, spectacular. Your translation seems fitting.

Dan: It took me years to do paintings here in Italy, meaning paintings that I could look at or exhibit. I believe you work from where you are. I had many ideas about how I should paint, and while co-teaching in Italy with many terrific painters. One starts to believe in certain rules and devise certain ways of working. You want to fit in. One wants the work to stand up to other painter’s ways of working and painting from the landscape. You get into this thing of what can you do vs. what do you want to do. It took me years to try to even get away from what do I want to do as opposed to what I can do.

Tina: When you go back into the studio, do you imagine or recall the landscape to paint back into your paintings?

Dan: You know how we all tweak things. You pull things out; push things around, little things, but not a lot. I don’t work a lot away from the landscape and I’ve learned only do this in natural light. When I use electric light, the color shifts are all off and I end up with two different paintings.

Tina: I’ve heard you say before that being capable of creating scale is more important to you than the physical size of the painting. For example, a small painting can look big.

Dan: The idea of scale became so apparent to me in Italy. Landscape painting for me is so much about seeing from here to there and about how one creates relationships that work or fit together in this vast space.

Larry: So a miniaturist could do it?

Dan: Right. A lot of people think scale means the size of the picture but it doesn’t at all. It’s the relationships to the parts. If you look at a Van Eyck, the painting looks immense, but it’s physically it is really very small. I’m not that good, so I can’t do that. In a way, I use size to get scale. Which maybe is a problem, but I’m okay with it.

It’s that battle between your intuition and what your mind tells you to do. For years I kept doing these smaller pieces and then I realized it’s like an ocean out there. How do I paint the sea? Do I want to paint a little part of the water? It started to extend the painting both horizontally and vertically. The wider it got, the deeper it got. Again, it’s that thing, a lot of people paint shelves and others paint distances.

Tina: That’s a great way of talking about painting the landscape. Thinking of the landscape/ sky as a sea. It’s a wonderful metaphor.

Dan: There is a kind of arrogance too. There’s a kind of extreme narcissism to try to take in all of this. And the more I would distance myself from other painters to see how they saw and painted Italy, the better my paintings became. That was hard for me because I had to find a way I could believe in making a painting from a landscape, yet, still feel I was making my own paintings.

Larry: Why do you perceive of it as arrogance?

Dan: Maybe it’s not arrogance, but the hope that you can do something so difficult and still get it somewhat right in relationship to what you are seeing.

Tina: How does one of your paintings near completion? I’ve heard you say you don’t make drawings, or preliminary studies.

Dan: If I look at something and there’s kind of wholeness to the experience, and I know that I don’t want to reopen the whole painting and/or I stop having ideas about it, things don’t jump out. I wouldn’t say it is finished, but I would probably say the painting is resolved. I think for me, drawing sets up the finish idea, the completion, and I think more about the color idea and the disposition of masses on a plane set up a different expectation. In a way, I can never finish a painting. I stop working on it, but they always seem open-ended to me. That’s why I work on paintings for years sometimes. Constantly changing them to the conditions present, yet hoping and believing in the resolution in the end.

Tina: We asked you about composition and abstraction. I’m wondering if the organization or if the abstraction reveals itself as you are initially looking at a vista or as you paint it?

Dan: Because I am so involved with seeing this world, I don’t believe there is anything really abstract out there, its all real to me. I think that’s pulling in an idea of painting into the landscape. Again, I don’t see anything in the world as being abstract. I mean they’re formulations of an image based on seeing. Obviously it’s not the thing I’m seeing. It’s a re-presentation of the thing I’m seeing, and of all the decisions and changes that I make while “seeing” what I am painting.

Larry: Isn’t that just another way of saying abstraction?

Dan: Yes, possibly, but abstraction is not the way I think about making a painting. What I am trying to do is to visually link together successive moments in what I see in front of me. Or, you might say a specific piece of the world as it is in that moment. Each moment is based on trying to find that equivalent in paint while always fighting assumptions to what I am looking at. The painting is built, then, from that succession of decisions and corrections until I find a kind of unified resolution of the whole painting. This is why the weather is so important to my landscape paintings, because that determines in the most specific sense what is happening in front of me, yet is constantly changing. That is the chase I am on.

Tina: Your paintings require a slow read, or a process of getting to know them. I also find the periphery of your paintings charged. Are they seem to be meant to see not from one point of view, but from all sides.

Dan: I like to move the canvas so that you come in from the edge on different angles, so that you don’t get a static vanishing point. I don’t create a space where everything leads in to one point and try to take different points of view from varied angles of the painting to get different things happening, from different sides and different angles of vision. Lester Johnson talked to me about this.

It also shakes up your idea that you know what you’re doing. When you get out there, it’s beyond any sense of your comprehension. The more I get into it, the less I know what I’m doing, the less I compose, the less I think about say Corot or other landscape painters, that’s when I paint better. Whereas, if I want to compose, I am lost and spend the rest of the time painting, fighting against that very idea of composition, that I imposed on the painting in the first place. I don’t want to think about making a certain painting, or psychologically align myself with other paintings. Better to ignore all that gets in the way of what I am seeing now.

I think that’s the hard thing, knowing you’re not a great painter, but going out there and painting. We’re all taught to be great painters. When, in reality, hardly any of us are. That’s a very difficult idea for the ego to digest. As students all we hear about and see is great painting. I think, for me, I have to be able to accept this idea that rather than try to be a great painter, you do the best you can and that’s got to be good enough. I go for progress not perfection.

Tina: The impossibility of painting?

Dan: No, I’m just not good enough. Other people can do it. That’s the hard thing for me is to go out there. That’s the hard thing for me, is to go out there knowing full well you’re just doing your best and it’s not going to measure up to great painting. That’s the tough truth about painting.

Larry: What about just saying, “Oh, well I’m unhappy with this particular aspect of my painting, therefore I want to concentrate on bringing that to a higher level”? It’s not like you just sort of accept the idea that this is all I can do. Don’t you keep moving it forward?

Dan: Oh no. I’m talking about the big picture. In the little picture there are the nuts and bolts of painting. There is the moving of things, constantly repainting, not protecting your assumptions regarding what you see and paint. Of course we address what does the painting need, there is that. But that’s different than what I’m talking about. Yeah, that’s all I do. All I do is look at what’s wrong.

Larry: Is there something about a painter’s innate abilities or character that limits how far they can go with their painting? That painters like Corot or Antonio Lopez Garcia are impossibly rare?

Dan: I never think about it. That just gets me into a whole world of problems because there are so many good painters out there. I think this is an incredibly strong time for representational painting. They are so many people who really believe in it, and are doing fantastic work. You start looking at it and you just start to see how good it all is. Yet, for my own psychology it is a double-edged sword. Constantly seeing all this terrific work inspires me in many ways, but it also wears me down a little. And myself trying to control how my painting “looks” in comparison to other artists.

You know, we can all relate to Corot’s paintings. We see the world a little like that and we can all paint a little. And there is a commonality there that we can all share. No one can do that with Cezanne.

Cezanne led me more to the intuitive as opposed to the intellectual. This is why I love Cezanne so much. He is such an intuitive painter. Nobody speaks about Cezanne anymore. He doesn’t conform to people’s ideas about painting at all. You never hear people talk about him because you can’t find a hook into the painting. We are all looking for how to paint and Cezanne does not reveal that.

It is more difficult because there is no hook, because it’s about the way this amazing artist changed painting. He just drains it of any type of humanness so there is no cliché in his work. He was an incredibly intuitive artist who painted the world as if seen for the first time.

Tina: That’s a great way to put it.

Dan: That’s the hardest thing for me to do. We all have memories, we all know how to paint, and we all think we’re good, we all talk to people, and we all look at art. For me feeds into a think-tank of the clichés that you carry with you every time you paint. Cezanne was able to just break through all of that, which has to be the hardest thing to do, I would think.

Tina: You worked with Wilbur Niewald at the Kansas City Art Institute. What do recall about Wilbur’s teaching?

Dan: Wilbur changed my life. He introduced me to this whole idea of painting from observation, directly from nature. He gave me a sense that it was possible and worthwhile to work from observation as opposed to painting conceptually and I started to find myself in that idea. I was very close to him. He was the guy that got me started painting in a very committed way, so that my life revolved around painting. Through Wilbur I began to understand the difference between looking and seeing. This is the foundational idea and thrust of my work to this day. I don’t know that I would have been a painter if it weren’t for him. I had never thought about being a painter. But somehow it resonated deeply with me and I thought it might offer a new direction to my life. Somehow it seemed appropriate and immanent. I met Wilbur and he just took me under his wing. I trusted what he said and allowed him to help me find myself as someone who is a painter. He brought me to this whole idea of observational painting.

Larry: And was Stanley Lewis at KCAI then?

Dan: Wilbur was my main mentor. He talked a lot about Cezanne and about this idea of seeing. Stanley was teaching next door, but Stanley was too much for me then. I loved his work, but I just didn’t have that sensibility, I don’t have that energy and intensity. I’m much more of a slow, ponderous kind of guy. Stanley’s all about painting with an extreme kind of energy, so at KCAI I really gravitated towards Wilbur.

Tina: Then you studied in the MFA program at Yale in the ’70s. What was it like as a student working with William Bailey, Andrew Forge, Bernard Chaet, and Al Held?

Dan: I studied with Al Held a little, but he was very tough and probably not that interested in what I was doing. He came from a very different position. Mostly, I worked with William Bailey, Bernie Chaet and Lester Johnson. They were all very supportive and talked to me about very different issues regarding my work. It was pretty much the formal stuff we worked on.

Larry: What kind of painting were you doing?

Dan: I was working on large paintings looking out from my studio window at the street and cityscapes below. I would paint from the light and life on the street, watching how it changed from moment to moment, painting in and painting out of situations as they occurred throughout the day. My canvases corresponded directly to the size of the large windows I was looking through. At that time the work was big for representational painting.

Larry: Why did they encourage big paintings so much back then?

Dan: I don’t know if they did encourage it. I just felt it was necessary for my work. I recall one day Al Held came into my studio to look at what I was working on. I was painting these small still life’s of apples, fruit, pots and stuff. He looked and said, “You can’t do that anymore. It’s over. You just can’t do still life any more.” These were really heavyweight painters and they were saying, “You’ve got to find something else to paint.” Held said, “Look out your window. That’s better than these paintings.” So I did.

At first I started doing small paintings looking out my window, but then I got into the same problem of size and distance and the idea of including whatever I wanted to paint. I began painting the whole window and the paintings kept getting bigger and bigger. The paintings became more narrative and I started to get interested in what was happening down the street. I’d sit there all morning and hunt for these little episodes.

Tina: And that became the narrative?

Dan: Yes, the cars, trucks, people interacting and the narrative of the color and people walking by as well as the constant process of seeing “change” and then repainting what I saw. I would paint whatever I wanted and then I’d paint it out. I got into this mode of painting the flow of things as they happened. And that’s when I began repainting a lot. I think there was only one other figurative painter at Yale when I was there, so there was a heightened sense of feeling kind of alone and isolated regarding the direction my work was going. So many other things were happening in New York and the kind of painting I was interested in was not at the forefront of what was being shown or discussed.

Dan: Once Fairfield Porter visited Yale to give a talk. I remember he was practically booed off the stage. People attacked him for being an elitist, living on his own island and for having a position that stood for the sake of artistic perception.

Larry: That’s ironic because he was leftist politically.

Dan: He wrote the art and technology essays. But students saw him as an elitist and criticized him. “You have no right because you just live on a little island in your secluded world, and you just make little pictures of your house”. I saw him as more a poet/painter than as someone who wanted to re-invent art. That concept seemed lost on the audience.

After the lecture I went up and talked with him, I thanked him for speaking and told him I thought he gave a great talk. He asked me if he might take a rest in my studio, and commented on the tough audience. He walked into my studio and looked around. I asked him if there was anything he could tell me. He replied, “The only thing I can tell you is paint what you love.” At the time, it really helped me and gave me a kind of support. I have tried to take his advice to heart ever since.

William Bailey was really helpful. He would come and talk to me and would show me paintings. We would look together and he would ask questions like, “Why do you think this is here? Why is that there?” This helped me to start thinking formally about a lot of different issues in paintings. Bailey is very much about the stillness in a work, how forms and color relationships pulse and don’t really move. William Bailey and Stanley Lewis are my favorite painters and the two people who have influenced me above all.

I also worked with Lester Johnson, who got me into this whole idea of directions, as opposed to moving in and out, moving across the surface, side to side and up and down. He was very much interested in activating the space with diagonals and packing the space so that everything stays up front on the picture plane.

Bernie Chaet was a wonderful teacher and later a great friend. He was supportive of everyone and there to talk about the problems we were having in our work. Bernie loved looking at paintings and transmitted to us this love of art and how paintings are developed from the point of view of the artist. We stayed friends and he was a constant source of support to me and many other young painters.

Tina: What was your association was with Andrew Forge; did he play a part in your study?

Dan: Yes, I met him, he wasn’t at Yale when I was there, but I was a friend of his wife Ruth Miller, and we would talk a lot about painting. I met Andrew through Ruth. He spent about six weeks here in Italy, for two summers I think. I would sit in his studio and watch him paint, and we’d talk, but so many of the things he talked about were beyond any understanding I had at the time about art and aesthetics. I think he was kind of a genius. He would look at something then look out the window, he’d be smoking his pipe, I’d be sitting in the back and he would just look at something and put down a mark, and then walk back and sit for two minutes looking at the spot or mark he just made seeing its relationship to the other marks as well as what he might have been looking at out the window. That’s a long time to look at one mark, and then walk up and do another one. It reminded me of stories about how Cezanne painted and the gap in time between what piece of nature he saw and what piece of paint he put down.

Dan: Andrew was very supportive and positive about my work and at the end of the summer we traded paintings. He said to me, “I really believe in you Dan, you keep going, don’t let people talk you out of it, stay strong and committed to your vision”. Really, all these people I met, I never really wanted to paint like them. I never felt I could, I couldn’t paint or draw well enough. But I had a kind of willed ambition, not so much for the career but for my work. My ambition tended to go always towards my work, and how to be a more truthful painting. I was showing at Forum gallery then and Fischbach really took an interest in me and helped me.

Yale was great, the final thing Bill said to me at the group show, “Well, I don’t know what to say. Now what?” And that was it. It was kind of like, “Go little fish”. I always wanted these guys’ approval. They would give it to me but never in the ways I really wanted. It took me a long time to be able to understand what they saying in their own way, and not the way I felt I wanted, which is really the last thing I needed. They never wanted painters to paint like them. They never wanted your work to be like theirs, but were always trying to help you make your own paintings.

Tina: Do you try to do that with your students now?

Dan: Oh yeah, I think the worst thing is if the student feels they need you or if they feel they must paint a kind of work that reflects back to you as “their” teacher. I am not interested in students painting like I do. I try to teach much more about seeing and how to understand the decisions, changes and assumptions one makes seeing and how that is brought to drawing and painting. I really try to create an experience so that students are always thrown back on themselves. For example, if they ask me something about how to paint or something like that, I respond by asking why they posed a particular question. And suggest that they might find out more by trying to “see” what it is they are looking at and try to see it in different terms than they are at that particular time.

I want them to be able to answer their own questions and follow their own intuitions when they are out of school working on their own. You want students to get strong and independent so they can be on their own. That’s hard! A hard thing for them to swallow I think.

I really wish the best for students. I really love them and I love working with them. It’s just a hard gig. I can see they all have to have jobs and one day will have kids and significant others and they have to support themselves. How do you do all that and yet paint? It’s hard today. I worry for them, I do.

Larry: You’ve had times in your career where you have had these hugely important shows.

Dan: It’s not like I’m trying to put myself down, I’m just saying it’s not this stellar career. It’s a kind of steady career… I think people respect my work, whether they really like it or not. As I said, I have this kind of willed ambition to make my work truthful and that is what I think about.

Tina: It’s interesting to me that you’ve created a world for yourself that really does reflect your ambitions as a painter. And you recognize the length and breadth of the journey and serendipity required to continue working. It is a grand struggle requiring momentary and often monumental ups and downs. Doesn’t that describe the life of a great writer or painter? There are no guarantees…

Dan: Gabriel Laderman said, “Be ambitious about your work, not about the career.” Today that’s completely reversed. You tend to measure yourself against that. We all do, I think.

Larry: These things you’re saying are great. Good painting teachers help people realize it’s a lifestyle choice with a set of values about what’s truly valuable in life. Being a good painter is its own reward.

Dan: That is the reward. But, only if you don’t feel badly about not getting the level of success you feel you might deserve. And if you do, never take that outside with you or in your studio when you are painting.

Larry: The career should be less important than knowing that you have integrity as a painter and that you’re doing what you love. Nothing could be more rewarding. But then again, it’s obviously nice to have money and not worry about food or rent, etc.

Dan: Doesn’t it nag away at you? It nags at me, the whole fame thing.

Larry: It seems like it’s almost over. Like it’s not really possible, except for a very small minority of people. It’s time to figure out a new paradigm.

Dan: I totally agree with that. The other thing is that I don’t think it’s so much that I chose to be a painter; I think it chooses you, actually. I think when you’re a child, you’re a maker, you imagine. Then how do you create a life for yourself? Students ask me, “What do you think is the one prerequisite for being a painter?” I say, and I kind of mean this, “You can’t be good at anything else. You can’t want to do anything else.” They perceive that as terrible because now you’re supposed to be able to do all these different things and are supposed to wear many hats. It’s making a world. I think that’s the thing, in terms of when do the world and your vision start to come together? That’s the real thing, I think, for me. How do you start to make your vision and the world coincide? The painters I respect, the painters I really like, couldn’t do anything else. I’m sort of like that. I couldn’t do anything else. You’re able to re-imagine and re-invent your world. What a great thing.

Larry: I think it’s in the boundaries of your definition of painting. For instance, Piero was not only a great painter but he dabbled in architecture.

Dan: He was a great mathematician. But, you are talking about the top of the pyramid here. So that the inside is painting, the outside is informing the inside. For the greatest painters it just becomes one. That’s the hard thing. That’s kind of why this, whatever you call it, has became this overpowering obsession with me. How do I absorb this that I see and use it? How does it make me paint it? I try to give myself over to it. Again, the painters I like, come to painting with an incredible sense … they come on their knees. They are humble people in a way and great visual listeners. I think great painters take a referential attitude towards nature, time and space. I try to align myself more with those people, as opposed to Jeff Koons or Andy Warhol and that direction of making art that they come out of.

I’m down here. I just do what I can do. You’re talking about the ten geniuses in western art. They can do anything.

Larry: Right, I agree.

Dan: That’s where everything has gone. I met Warhol once and I’m telling you, I felt I was around evil. There was something incredibly pernicious about him. It was a bit scary.

Tina: You also met Picasso once, can you say something about that?

Dan: Oh I did, yeah, as a kid. My mom once said to me, when she was alive, she said, I was having a bad day, this was maybe 15 years ago, 18 years ago, and I said, “I feel just like a little Chicagoan.” She asked, “Why’d you just say that?” I replied, “I don’t know, it just popped into my head.” “This reminds me of something I haven’t thought about in 50 years.” When I was a kid, we had a friend who was a dealer and we used to travel in Europe. The dealer said, ‘Why don’t you go visit Picasso?’ We had lunch with Picasso and Jacqueline. The minute he met me he just took me into his studio, he said, “Let me take the little boy.” He put me on his shoulders. I guess he loved carrying kids on his shoulders. I spent all day there.

Larry: Wow.

Dan: Yes, I don’t really remember it, but he gave them a pot and he gave them a drawing, which they lost. As we were leaving, he took me on his shoulders and handed me to my parents and said, “You’re my little Chicagoan. ” Somehow I think I remembered the phrase… I don’t know, because I would never have used that phrase.

Tina: Earlier you referred to ‘outside painters’ and you spoke about how painters look for a home. Can you explain what you meant?

Dan: Yes, but I am referring to those painters I like, those painters who seem to look for a home. I am not sure Duchamp looked for a home.

Tina: Alex Katz spoke about the landscape as being a question of how much light a painting can hold. When I see your landscapes I feel like they are bursting with light from corner to corner.

Dan: Well the light is everything for me. You turn the lights off and it’s a dark room. Everything I see is light. For me there is a kind of light that works with and captures my imagination and makes me feel like I am home. I long for this light, for this recognition; it’s what I search for in every painting, although it is seldom realized. That’s what I am after and what Italy held for me. Italy made me see a kind of light that was both light and a painting simultaneously. When these two elements coalesce there is no division between the light and the landscape. Perhaps it is because I lived in the Middle East, Europe, and lived in California in my early years. There the light is similar to Italy. I think so many painters whom I love and look at are all in search of their light. They just recognize it when they find their landscape. When the inside and outside line up, my search ignites and it is the intensity of this search that is something I find in those painters that I admire.

There is this idea of sunlight that infuses everything I think about, as opposed to the darkness, like we would find in a Ryder painting. Ryder is someone whom I really love, but that is not what I see as a painter. One can try to change that or try to deny it, but for me the best thing is that I go with it as much as I can.

Tina: You mentioned your dreams; can you tell us something about how dreams play a role in the large narrative paintings?

Dan: Some years ago, I was living alone and painting without interruption, both in Chicago and Italy. My imagination was so active. I found a way to stop a dream, then enter into the dream so that I became part of the story as if I in a movie. I could control things and travel around in the dream and see things. Then, I would come out of the dream, wake up and do a small painting of what I’d experienced. The next morning, I would gather all these little paintings and recall the context of the dreams. I used to be able to do this, but I really can’t do this anymore.

Larry: How big were the paintings?

Dan: Around 6” by 6”. They were tiny. I would use them as triggering mechanisms and as imagery. They became something I could use to create the larger narrative paintings, which weren’t really about the dreams, but instead were about the collective of the smaller paintings. Before that, I used to paint from models, and would set up domestic situations, women getting out of bed or cooking or you know, things like that, sort of a housewife. But it just didn’t resonate with me at all. I realized, I had to find stories that I believed in, and I really didn’t believe in my domestic paintings.

When I started to jump into this dream imagery, I was for the first time able to believe in the stories I was creating. They made linkages from imagery that I felt was real. I didn’t understand them. But rather, the understanding came through the process of painting.

I don’t think about composition anymore. I don’t pre-draw things. I used to think it about it a lot. Now, I sort of accept what I see as a given. And my job is to really see it. So I let the scene make the composition. I probably know pretty much about painting and painting ideas. But once I go out to paint, I try to keep all this out.

Tina: Can you describe the relationship between your large narratives and the landscapes?

Dan: For me the narratives are very related to my landscape paintings, in that I completely believe in what I am seeing. Be it in the actual landscape or in the imaginative sense of making a world that is real to me both psychologically as well as visually. Each form helps me to paint and to see the other. The gap between the two is what interests me.

Larry: And how do the demands of the landscape paintings fit into the narratives and visa versa?

Dan: The landscapes help me paint the narratives and the narratives help me paint the landscape. The hard part is how do you believe in them. When I am in Chicago I have to fill in this gap. But, once I get into the large narrative paintings I fall back into the language of painting. The hardest part is figuring out how to believe in the paintings, so you don’t have this gap.

While the painting language is the same, the intent is different. In the narratives, I try to find what is underneath, what is submerged in my imagination and how through the process of painting and repainting, I can bring it to light to remake the imagination into a painting form that is material and real in the same terms that I would pursue when painting from the landscape. I am working from pieces of dreams, fleeting thoughts, and buried impulses, that through the act of painting come to the surface. All this is then reconfigured into the painting so it works and lives together, but in a new form, one that I could never anticipate or coax out. Perhaps one that comes from the struggle of images that must be remade into a new whole, which is the sum of countless changes and revisions, each fighting to stay in the painting.

This is also the process I experience when painting in the landscape. I work on paintings outside in many different light situations and weather conditions until a whole form emerges that makes sense as the painting comes to light. This is the gap I work best in, I try to slip away from what I know or think I see into this other way of working where doubt becomes the fuel and the intelligence in making the painting. That’s when I feel most alive as an artist.

Such an insightful interview. For many years I was Laura Sheridan’s (Dan Gustin’s first cousin) close friend, and of course I remember his parents and their Brentwood home very well. Yvonne never mentioned the Picasso story. Love that. And I miss Laura every single day.

Always was interested in Dan & Chris’ careers. Such a creative family. B

I never heard of this guy, so thanks for the introduction to his work. I think he undersells his work. Not crazy about the narratives, but he captures the light in those landscapes effectively without the garish use of color so prevalent in a lot of landscape painting today. I think he’s a better painter than he gives himself credit for, and his comments about Cezanne are spot on. People often say Cezanne deliberately distorted this or that, deliberately tilted the table top, but I agree with Mr. Gustin. Cezanne did those things intuitively. If he didn’t, his work would come off as mannered. So Mr. Gustin is a perceptive painter on that level as well.

Wonderful interview! Really amazing artist and very insightful on all levels!

Massive love for this incredible man – a brilliant painter and a truly gifted teacher. I know first hand that he has changed the way a great many people think about painting.

Great interview. I studied with Dan many years ago. He is a great teacher. His Ideas still resonate with me today. His values – deep engagement in the process, humility before the work and nature, constant learning, comparing your own paintings to the best work out there, and teaching students to ask their own questions.

What a splendid interview!!! Dan’s humanity and humility come clearly through in his responses to probing questions. I am now as fond of his thinking as I have been of his painting. Superb!

Fantastic and insightful interview. I studied with Dan at the Art institute of Chicago and he was one of the best teachers I’ve ever had.

In the summer of 2009, I spent six weeks at the International School of Art studying painting with Dan Gustin. He was an incredibly direct teacher, articulate with a minimum of words, supportive without the sugar coating. I asked him: “Teach me what are the rules of painting?” Dan replied,” There are no rules. You must first learn how to see.”

Lennie Mullaney

Portsmouth NH

I studied with Dan in the mid-nineties as a graduate student at SAIC. Through our discussions about Morandi and Matisse he helped me understand that paintings are in a way artifacts of your daily routine. He had me count the number of colors in the Matisse’s in the museum, and we laughed about how Morandi lived with his mother and spent his evenings. So much serious mythology surrounding simple people who loved to paint. Keep it simple and be happy. That’s what I took away from my meetings with Dan. He will always be one of my favorite teachers.

I studied with Dan in the 1990’s at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Best painting and drawing teacher I’ve ever had. Incredibly direct and honest. Makes one think a lot. I still use some of his teachings in my work today. Thoroughly like and respect his work and his work as a teacher.

I studied with Wilbur along Dan at KCAI. Wilbur was a life changing teacher and Dan was the best if the best student!