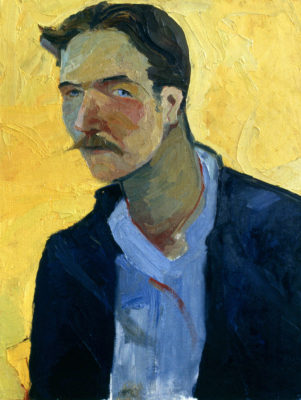

I was recently introduced to the work of artist, Christopher Benson while visiting his gallery, EVOKE Contemporary in Santa Fe, NM. I was intrigued by the strength of his compositions and execution as well as the wide range of styles he has worked in over his many years of painting, embracing traditional painterly realism to abstraction. I was also shown a video of his artist talk and was taken by his many thought-provoking ideas about painting and his willingness to “question authority” by art world rule makers.

In a short essay on the artist’s website, Benson states;

…”I’ve always had a “painterly” approach, with brush and knife marks clearly evident in my surfaces. It’s challenging though to find a physical abstraction which doesn’t just recycle the big gestures of the New York School, or call up the ubiquitous handmade vocabularies of Bay Area painters like Park and Diebenkorn. Even so, I have no interest whatsoever in the slick abstraction that proliferates today across the internet. So much of contemporary painting has become too neurotic about novelty — too determined to distance itself from any reference to its own origins. Manet was able to be startlingly modern while still openly tipping his hat to the masters who preceded him. For me too, an art that cannot comfortably retain some of the hoary residue of its own history is no art at all.”

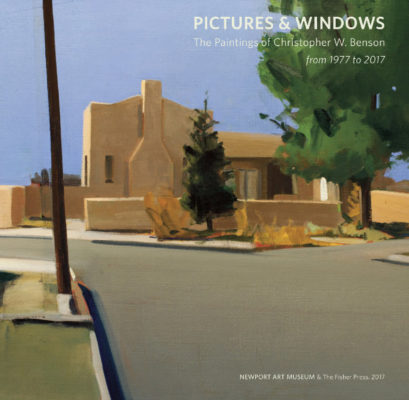

He agreed to an interview over email and a Zoom conversation and generously sent me his retrospective catalog from his 2017 Retrospective at The Newport Art Museum, Newport, RI, Pictures and Windows, The Paintings of Christopher W. Benson. This gorgeous book was printed by the Fisher Press, a company run by the artist that specializes in printing high-quality, limited edition artist books.

Christopher Benson is currently showing his work at the North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks, ND, through August 2022 in a Two Person Exhibition with Sue McNally.

He has twice been the recipient of The Pollock-Krasner Foundation Painting Fellowship, has shown his work in many venues nationally and has his work in MoMA (The Museum of Modern Art), New York, NY, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks, ND, The Newport Art Museum, Newport, RI and several others. He has a BFA in painting from the Rhode Island School of Design. More info can be found on his website I thank Christopher Benson for putting the time and effort into our combined Zoom and email interview.

Red White and Blue Collage #1, 2021, oil painted on linen fragments collaged on panel, 12 by 12 inches

Larry Groff: How did you learn to paint and draw?

Christopher Benson:

I began drawing as a little kid and never stopped. In grade school I was the guy in class who drew all the time. I began taking more formal drawing lessons at about age thirteen, and at about fourteen I began teaching myself how to paint in oils. I was lucky later to get a comprehensive three-year painting course at my high school in Vermont with this terrific painter named Peter Devine who came to teach there. That’s when I really began to learn how to paint.

LG: You went to the Rhode Island School for Design; what was that like for you?

The first year and a half were great, and I got a lot out of that time, but the painting program began shifting in my second year from a sort of modernist/pure painting approach to something more market-driven and trend-conscious. SoHo in New York was the hot scene at the moment and so was the Cal Arts school in LA, and several new teachers came in from both those worlds who were following the trends. They didn’t like me much, and I didn’t like them, so it all soured from there.

But when I got to RISD in 1979, the teachers there were mostly old guys in paint-spattered chinos and ratty sweaters with patches on the elbows, chain-smoking Camels or Lucky Strikes and swilling battery acid diner coffee out of Styrofoam cups. They didn’t seem interested in fame or money so much as how to make good paintings. They wanted to teach us how to see what good paintings looked like, so maybe we could learn to make ’em too.

The new teachers were much more focused on what was happening in the market. Who was big at Castelli’s or Mary Boone’s began to be as important as the work itself. Who was making the big money? Who were the hot new commodities, and WHY were they hot? Warhol coined his now ubiquitous bon mot about everybody becoming famous for fifteen minutes. I thought it was just a typically deadpan bit of Warholian irony, but my classmates took it seriously. All of a sudden, guys like David Salle, Jean Michel Basquiat, and Julian Schnabel were becoming seemingly overnight sensations in New York. Big money was being made off of the hip-looking stuff they were making. Around the same time, Jasper Johns, the first living artist to do so, broke a million at auction.

The Grand View Dairy Farm (first major commission – restored in 2017),

1985, oil on linen, 48 by 60 inches

I wouldn’t call any of those people a particularly great artist (including the much-celebrated Johns). But it didn’t matter. The market success and that larger-than-life art world persona were what the kids wanted, so that’s what the schools started to cater to: bundling all this self-consciously fashionable art together with a load of pretentious “artspeak” designed to stroke the egos of the Reagan-era “Masters of the Universe” who were lining up to buy this stuff because some joker in designer frames told them it was “important”. The prices skyrocketed and I think the quality of much of the work declined. The young superstar painters who came out of famous MFA programs like Yale’s or RISD’s or Columbia’s from about the mid-1970s on — Chuck Close, Lisa Yuskevage, Dana Schutz, John Currin, etc. — were what I think of as Art World Artists. To me they’re like illustrators with lofty pretensions. Like the Bouguereaus and Gerômes of the 19th century, they’re products of the academy. And that, to me, is the crux of everything I take issue with about contemporary American art and its market: It’s pretty academic.

LG:

Your writings about paintings show a great understanding and wisdom about painting. Why didn’t you pursue teaching?

Christopher Benson:

There are several answers to that question.

1. I never wanted to teach in a school because it’s all too organized and regimented for me. I’m too infernally independent for that.

2. I have a family to support, and I literally can’t afford to work as a teacher. I have a young painter friend who has to have a second job to supplement his college teaching job because it actually costs him more money than he makes to do it. That’s absurd!

3. The art colleges, and even the high schools now, have become completely beholden to the degree-program credentialing mill, so that no matter how good an artist you are, you can’t get hired to teach art without an MFA. The accrediting organizations, like the CAA (College Art Association), have a vice-grip on the whole process by demanding that anybody hired to teach art at almost any level must hold that degree. This, to me, is ridiculous, and an almost iron-clad guarantee that the people teaching art are going to be a pretty mediocre crop, who then just keep turning out ever more mediocre artists and teachers. It’s the fabled bird that flies up its own ass till it disappears completely.

LG: You sometimes come across as someone not afraid to question authority. You stated, “The minute we submit to any form of group-think, we also risk giving up our ability to respond honestly to the world’s surprises.” Can you tell us something to illustrate both how this played out in your life and the ways you’ve been able to cope with this? What would you recommend to students today?

Christopher Benson:

If you want to be an artist, walk away from school as soon as you can. By all means, go there and get the foundational skills from somebody who actually knows how to do whatever it is that you want to learn how to do. You can get all of that in a decent undergraduate program or privately with a knowledgeable practitioner. I did both things multiple times. But I also spent thousands of hours, all by myself, in major museums and galleries on both coasts of the US and in Europe when I traveled there in my twenties. Looking deeply at, and learning to understand, other artists’ work is the most important schooling you’ll ever get after learning the practical foundation.

But I’d also say, do the risky thing and skip grad school. Going there might make you a canny art world operator, but it can also kill your art dead. Robert Storr, the former director of MoMa in New York who later served as Dean of the Yale Art School, said when he was there that the most important contemporary art was being made in graduate programs like Yale’s. I don’t think that’s true at all. To me, some of the least substantial art being made today actually comes out of those places. The “top” MFA programs are more like MBA programs. They polish the student’s ideas and practice in order to prepare them to enter the workforce of the contemporary art market as solid earners. Some galleries, consultants, and collectors even go to grad school exhibitions and crits looking for the next sensation, the next young hotshot who is going to hit it big in the scene and whose work will prove a valuable commodity worthy of investment. The operating presumption here is that it’s even possible to teach a young person how to make good or important art — that there’s a formula for all of that which can be delivered by instruction. My uncle taught in the MFA program at Yale and he was very proud of how they would “tear the student down and then build them back up again.” All you get when you do that is a bunch of students whose work looks the same and has the same vibe and values of that school.

LG: That’s a pretty strong statement! Don’t you think there are at least a few MFA programs left that still teach painting in a positive manner?

Christopher Benson:

Of course there are. There’ve always been outstanding teachers hiding in plain sight all over the place — men and women who light young minds up and turn them on. I had a couple of wonderful painting teachers at RISD who also taught grad students there, and my uncle who taught at Yale was a fantastic teacher, just a natural. He taught me a hell of a lot. But I completely rejected the tough-love, boot camp, tear em down to build em up approach to art education and I never let anybody do that to me.

But really, it isn’t the individual instructors who I have a problem with. It’s the whole careerist mission on which the MFA programs have been based, ever since their founding in the 1950s. It was the very idea of creating a professional school in which an artist might be trained to practice in the market — not just in the commerce of the gallery, but in the market of ideas and movements, and in the ongoing instruction of other artists within that system. There is always a presumption within any academic system that there is some codified guide to practice which can be stored and authoritatively delivered by it. That, to me, is completely antithetical to the life-force of art, which is profoundly individual, exploratory and, if successful, revelatory.

LG: If a student wants to succeed in today’s art world, get a plumb teaching job and show in the venues that will advance their careers, won’t they need to learn how to intelligently maneuver themselves through our art schools and art world, however imperfect?

Christopher Benson:

You just put your finger on the problem with that phrase: “… succeed in today’s art world, get a plumb teaching job and show in the venues that will advance their careers” I don’t believe that a single one of those aspirations you just listed have a damn thing to do with making good art, and THAT is the problem! You know — not everybody is cut out to be an artist, and this idea which the schools trade on, that anybody can go in there, pay the fee and get “trained up” for the profession is just wrong. It isn’t a profession; it’s a vocation.

You have to be a very particular kind of weirdo to let this life take you on, and it just isn’t for everybody. A school can certainly craft a formula for success, but not for art itself; at least, I don’t think so. I think real art is the product of a far longer and far less predictable path that just can’t be dependably mapped at the outset. Being an artist has never been a “career” in the same way that other livelihoods are. It has a mystical component — sounds hokey, but I don’t know what else to call it — which is in direct conflict with all the things that guarantee career success. The problem with the Academies is that they are all about careerism.

LG: The transition after leaving school when young artists are finding their unique voices, separate from their teachers, can be difficult, especially when an aesthetic is tied to the perspectives and craft learned from a teacher(s).

Christopher Benson:

I think that happens when we believe that the teacher knows more than we do. It’s okay to believe that when you’re a kid and you don’t know anything. And we need to do that in order to learn and grow — to digest truly constructive criticism when it comes our way. But even then, the key to being an artist is to know inside that you see something nobody else sees, including your teachers. If you don’t have that sort of confidence, you’ll never make it. One of my favorite teachers at RISD once asked our class: “Who (other than yourself) is the greatest living painter?”

LG: Do you think becoming a great painter is likely due to nature or nurture?

Christopher Benson:

Ha! I’ll let you know if I ever get there. Seriously though, I think truly great art is something that can incorporate a lot of factors that then later become mistaken for its causes. Personal confidence and drive, talent, hard work and persistence are all required to become a good artist. But greatness — if it comes at all — is more complicated than all of that. I think it only comes when the artist surrenders to something bigger than themselves, which then ends up speaking through them.

LG: What, if anything, is more important to you now compared to what you were doing 10 or 20 years ago?

Christopher Benson:

All the same things are important to me now that always have been. When I was twenty-two, I was standing around in a group of painting students on the street at RISD; they were all talking about how soon they were going to make it in New York; how they were gonna get successful. One was going to work for this artist as an intern; another was going to take their stuff that gallery, and so on. It was all about the career track to Andy Warhol’s promised fifteen minutes of fame. I just listened in silence. finally, when there was a lull in the conversation, I said “it’s going to take me forty years to get to what I’m after.” That was exactly forty years ago last month. My show at the North Dakota Museum of Art, which just opened last month, marks an important milestone on that forty-year journey. I wouldn’t say that I’ve accomplished exactly what I was aspiring to when I originally set that timeline, but I’m closer to it now than I ever have been. This body of work is the first one that feels to me like my truly grown-up painting. It may not be great art — that’s not for me to say in any case. But it’s the most complicated and interesting art I’ve ever made, and I couldn’t have gotten to it without that long, forty-year journey.

LG: What can you say about what happens when painters change things up dramatically, like what you’ve been doing with your painting in both a realist and abstract style?

Christopher Benson:

There’re no rules in art once you become an adult, no matter how much folks want to tell you that there are. Nothing annoys me more than when some artistic colleague comes up to me and starts to give me an art school crit about what I’m doing. To which my almost universal response is (and should be) “Fuck off!” Rules are for students; we use them to learn how to make things well and then also to learn why and when we should break them. One of my favorite art quotes is from Beethoven, who said of another musical theorist: “Albrechtsberger forbids parallel fifths? Well, I allow them!!”

LG: How do you start a new painting? Do you make a lot of preparatory drawings and studies first, or do you tend to dive right in with a loaded brush?

Christopher Benson:

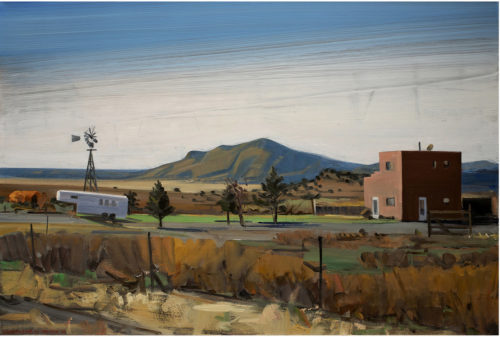

I learned to paint by working from direct observation, from on-site drawing, and painting from life. But I also have often used photography in my process. I don’t copy photographs exactly, but I use them (photographs I took myself, mind you) as a framework for composing. I pull out all the extraneous detail and move things around till I get a composition I like. Over the past ten years though, I’ve worked almost exclusively from my memory and from my head. My seascapes and landscapes, and also my recent abstracted landscapes, are often completely invented and there is no other reference material beyond a kind of free-associative building of the picture on the canvas. Ironically, I often make drawings after completing a painting, so that the painting becomes like a preliminary sketch for the drawing.

LG: What is your average workday?

Christopher Benson:

I’ve never been a strict nine-to-five, standing at the easel worker. I put in eight to ten hours a day doing all sorts of related things, and I do that at least six days a week, if not more. But I actually paint — with a brush in hand — in concentrated bursts of three or four months at a clip with breaks in between to write and do book work. When I’m in one of those periods, I work pretty fast and only for about four or five hours in a session, but then the sessions get longer as a painting progresses so that towards the end, I’ll find myself putting in anywhere from ten to twelve hours.

LG: What do you think about color and tonality with regard to light and space in your landscapes and interiors? Would you say that you are likely to think about the tonal orchestration of a painting before color?

Christopher Benson:

I’m not wild about color theory. I like to say that Josef Albers worked out a marvelous formula for putting horrible colors together and then justifying them intellectually. That’s an exaggeration of course; there are people who work that way and do wonderful things. But I just don’t think of art in scientific terms like that. Yes, there are rules of chemistry you have to learn, and color has its own set of rules that it’s useful to know. But I’m more intuitive than scientific and I generally admire those artists who work the same way.

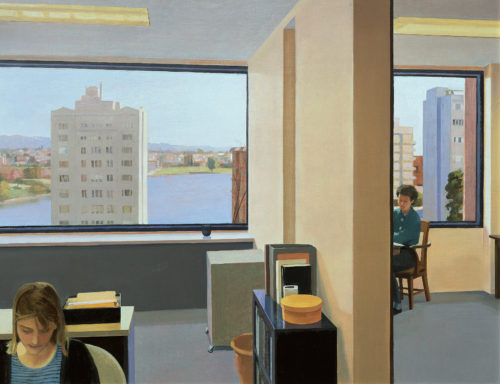

Don’t get me wrong: color is very important to me, as is tonality, though I do tend to use color more than value to create depth and space in my pictures. But the colors I use grow directly from one another as I paint, in a sort of call and response process. I rarely map anything out ahead of time, though I did make elaborate preliminary studies for many of my earlier architectural and figurative paintings.

LG: Do you use black on your palette? Any thoughts about using black?

Christopher Benson:

I love black. I use it a lot. You have to be careful though to balance its intensity and presence with pure colors that compliment and are not overpowered by it.

I also often use a mixture of deep ultramarine blue and burnt umber to make a black when I want a space that recedes into deep shadow. It’s in the more illusionistic representational pieces that this approach is warranted, I think. The chroma of the pure colors gives them spatial position, where black tends to sit up on the surface.

One thing I will say about black is that I only rarely mix it with other colors, and only then when the color I’m mixing it with has an extremely high chroma or intensity (saturation) so that it can withstand the dulling effect of the black. There are also many different black pigments with radically different personalities, so you want to pick the right one for the job.

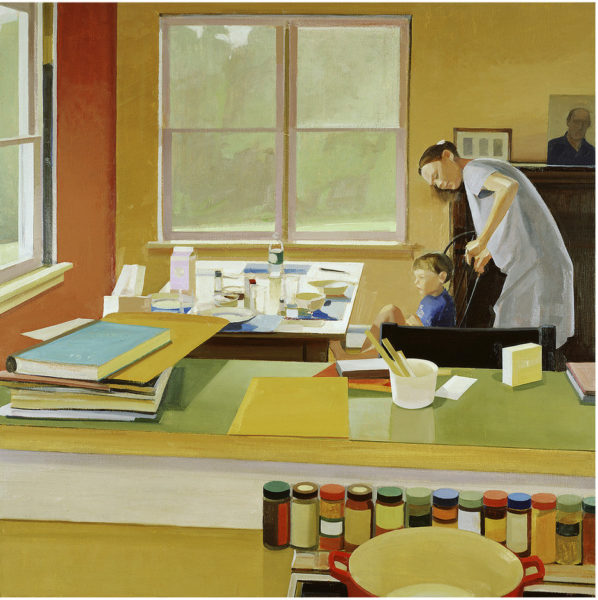

LG: In your books, you’ve talked about the calligraphic nature of your brushwork and how that comes from your long experience painting but also your family’s history. Can you tell us something about that?

Christopher Benson:

I have no control over the calligraphic thing. It’s just the world I grew up in, so it’s an inevitable part of my visual makeup. There’s nothing too deliberate about it. In fact, I think it’s what comes through when I’m NOT being deliberate. For years I tried to push it into the background in these rather stiffly formal architectural realist pieces, but it always finds a way out. Lately I’ve given up trying to hide it and I just let it rip. It’s especially apparent in my imaginary seascapes and landscapes.

LG: Can you talk more about the relationship between your representational and abstract works? What led you to make such significant changes in your work?

Christopher Benson:

Abstraction has always come very naturally to me, but I grew up in a family of hardcore traditionalists and realists, so I spent years shoving that innate abstracting inclination under the rug. As I’ve moved from my fifties into my sixties, I’ve been trying to stop controlling all of that. Coming out of a background of pretty committed traditional craftspeople, and also artists, I had a monkey on my back about the realism for a long time. There was a strong message in our tribe about the “right” way to do art. And the right way tended to be realistically.

My grandfather and dad (and now my younger brother) were all well-known letter-carvers and calligraphers, and my dad was a dedicated figurative sculptor as well. I also had a pair of artist uncles I was close to; both now passed. My youngest uncle, Richard (we called him “Chip”), was an influential photographer and photographic printmaker. He’s the one who taught for many years at the Yale School of Art and he even ended up as Dean of that school towards the end of his career there. He and my father both had strong opinions about the naturally occurring reality of the world, which they thought of as being superior to the messy emotional stuff inside our heads. Because of that, they were pretty dismissive of any art that wanted to address the interior life, especially if it was made in anything other than a strictly controlled and realistic manner.

Coming from that family art dynamic, my natural attraction to expressionism and abstraction — and even to the sorts of representation that speak through those languages— felt like it wasn’t okay; like I might “get in trouble” for doing it. I believed I had to buckle down and make realist work to show that I had the chops. So for years I made those rather severe representational paintings. But it was never where my heart was, so I finally just took the shackles off and have been trying lately to let the thing I enjoy come out.

I was lucky to have another uncle, Tom, whose talents and aesthetics were much more like my own. He was a natural abstractionist and an important ally all through my teens and twenties. Sadly, he died very young at fifty-one of a heart attack when I was just twenty-seven.

I will say though that the whole family were essentially supportive of my art, and it was a great place to come from despite some occasionally difficult ideological differences. I love them all and am grateful to have had them.

LG: What might you say about the ways your abstract paintings have similarities with your realist work? Do you ever worry that bravura brushwork ventures into being overly stylized?

Christopher Benson:

Stylization is something I’ve fought with all my life, but it frequently happens anyway. It’s just where I came from with such a graphic and design-oriented background in the family. My grandfather, who was the first member of our tribe to do the letter and sculptural relief carving, had a very stylized approach to design, and he and my dad were both calligraphers; so “Bravura” mark-making is just in my DNA.

LG: Do you worry that connoisseurship in painting is becoming increasingly rare? That fewer people can look at paintings critically compared to previous generations? Will people in the future still be able to appreciate the subtleties that make one artist great and another average?

Christopher Benson:

The number of people who really see what’s going on at the highest level of art, and of painting especially, is vanishingly few and always has been. But there were folks in the past who worked hard to understand it. That sort of Connoisseurship began to disappear when we got so much more interested in ideas in the conceptual era. The teachers, curators, historians and critics who were educated in those years (between the late 1970s and early 2000s) often don’t see paintings at all. All their attention is taken up with concepts, politics, contextualization and fashion. The people who really SAW painting’s magic disappeared for quite a while, but I think it’s been coming back in this century.

The people who see it best of course are the painters themselves. Anybody who is serious about painting for painting’s sake, can’t get good at it without becoming a connoisseur of their own medium. So at this point, I believe that it’s actually the artists who know vastly more about painting especially than the non-practicing professional experts.

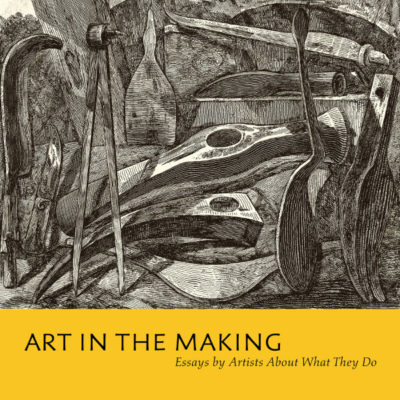

This idea of the artist’s first-hand, experiential expertise is actually what is behind a new book I’m publishing this year titled ART IN THE MAKING, Essays by Artists about What They Do. This is a collection of essays by ninety-one artists and artisans in which they talk directly to the reader about what they know and do. The book was intended to re-kindle a kind of personal connoisseurship that isn’t based on either critical or academic opinions or on the fashionable art world trends. We’ll see how that goes!

LG: In some of your paintings, I see a strong affinity with the Bay Area Figurative painters like James Weeks and Diebenkorn and painterly realists like Fairfield Porter. Did you ever meet James Weeks when he taught a BU?

Christopher Benson:

I never met Weeks, but one of the treasured books in my library is a little Hirschl and Adler catalog of his paintings that my first, and favorite, oil painting teacher, Peter Devine, gave me. That little book had a huge impact on me and still does. I love Weeks. I also loved Diebenkorn. His mid-1970s retrospective at the Whitney Museum was the first important retrospective of a painter’s work that I ever saw. In retrospect, I like Park a lot too, and when I lived in the Bay Area I visited and later had a long correspondence with Wayne Thiebaud, another much admired California painter. So yeah, the Bay Area crowd are also part of my DNA.

LG: What contemporary painters have you recently found interesting?

Christopher Benson:

I like the less celebrated American ones best – Sue McNally, Jennifer Pochinski, Janice Nowinski, Brian Rego, Leslie Parke, Gage Opdenbrouw, John Beerman (John and I went to the same schools in both Vermont and at RISD and we’ve shown together a few times. Sue McNally and I are also doing the North Dakota museum show together). Peter Devine was my teacher and mentor who is terrific,odd and wonderful. I think very highly of Vija Celmins as well. I also love the Leipzig painter Neo Rausch. I think Rausch and Celmins are two of the best painters working today, now that Lucian Freud has passed on. But I feel similarly about Anselm Kiefer – though he’s something beyond a painter to me. I’m not sure what the hell he is. But he’s a great artist! Peter Doig is pretty good too; I just wish he hadn’t gotten to be such a market celebrity.

LG: You’ve made several significant changes in your work over the years, abstract, realist, tight and loose. How has that helped or hindered you concerning these changes? Is there some aspect of your work that remains constant despite the manner or style you’re working in?

Christopher Benson:

I often compare what I do to what a classical or jazz musician does. If you listen to a great violinist play, they may vary between Baroque and Classical or even more modern music — all of which are dramatically different forms. But the artist is the same person with the same voice in all those cases. All my paintings come from the same place and are based on the same values and aspirations. I change the game up frequently in order to stay fresh and stretch my voice. But it’s always my voice.

LG: You talked about making a living as a painter and the whole notion of art as a commodity. You quoted from Oscar Wilde’s 1891 essay “The Soul of Man Under Socialism.”

“Indeed, the moment that an artist takes notice of what other people want, and tries to supply the demand, he ceases to be an artist, and becomes a dull or an amusing craftsman, an honest or a dishonest tradesman. He has no further claim to be considered as an artist.” I’m curious to hear more about what you might have to say about painters who don’t teach and need to make a living by selling paintings?

Christopher Benson:

This is a pretty complex topic, but I think a very important one. One of the things I propose in my new book of artist’s essays is that many people who make what once would have been considered less sophisticated or more commercial “applied” arts (i.e. craftspeople, illustrators, etc.) are actually no less fine artists than many who self-consciously try to avoid the appearance of being commercial.

As Bob Dylan said, we all “gotta serve somebody,” and the edgy art world artist is no less of a sellout than anybody else and maybe even more so due to the rather stunning hypocrisy of their pretense at purity. They engineer what they do to please an audience and conform to a set of standards that are no less constraining than the standards of a client. It just happens that for them, the “client” is the expectation of the art school that hires them to be an exemplar of the current cutting-edge trends, or it’s the gallery, curator or critic who exhibits, markets or writes about them in the same spirit.

Jeff Koons is no less crass and commercial than Thomas Kincaid (and only slightly less tacky), but he swaths everything he makes in an aura of cannily intentional irony which has, at least for the past few decades, been accepted by the art world as an expression of high art.

All of this is intimately tied up in the necessary commerce of the arts. The artist’s highest aspirations are inevitably bound up in her or his need to make a living— so we all end up doing our own version of what is necessary to survive. Some artists have family money, and that can make them quite free to experiment. But many don’t, so they have to find other ways to stay at work and pay the bills.

I never had a trust fund that would support me and allow me to paint all the time. As we’ve discussed already, I also turned away from the teaching track. I began in my teens to work as a tradesman, first as a carpenter and then later in the fine-art editions printing trade. But I was never willing to give up the need to spend at least half my time painting, so I had to learn early on how to make at least half my living from it. There were about twenty years — between my mid-twenties and mid-forties — when I did a lot of commissioned work. I painted portraits for private clients, and also for universities like Stanford and later for Duke (painting Dean’s portraits). I painted people’s houses, and the landscapes they liked; all sorts of stuff like that. That work was very clearly a form of craftsmanship which built my skills.

But in the background, I’ve always done another kind of work that was aspiring to something different from what the money-earning pictures were about. The commissioned work was always pretty hard-edged and realistic (and very stylized). But a more expressive and formally abstracted language was growing in the work I did for my own satisfaction and experimentation. In my late thirties I finally began to show those paintings in galleries in the Bay Area, and that was when I began to reduce the commissioned projects (though I still do them occasionally). The current abstraction grew right out of that Bay Area figurative style I’d developed while living in Berkeley in the 1990s.

LG: So what difference do you see between commoditized art and the art you are more moved by?

Christopher Benson:

I just remember how I felt in the early 1980s when I first saw Alice Neel’s paintings. That was when Neel got “discovered” after painting for a lifetime right there in New York in relative obscurity and poverty. I was seeing the hot young painters of that era in the New York Galleries, and they were mostly leaving me cold. Then this little old lady turns up, and she’s blowing every single one of them out of the water, at least according to my values.

Why? What was she doing? It isn’t that those guys didn’t do some okay work. They did. It’s not that they weren’t smart or talented; they were. But back then, none of them had anything on Alice. She was major, and they were minor, despite all the hype and buzz and fancy gallery affiliations and money that was lavished on them at the time.

I feel pretty strongly that when you go out as a young person, fresh out of art school, looking to manufacture a look and make a splash before you’ve made the big journey of discovery within the art itself — before you’ve lived the artist’s life, which is pretty hard — you’ve put the cart before the horse. I’m not talking about building the skills to make you a living; that’s different; you have to start in on that right away. But fame, accolades, critical approbation: these are all things that should result from truly transcendent accomplishments, not just canny production and marketing. A master is a person who’s spent a lifetime engaged in a profoundly difficult process, not somebody who went to school and got a piece of paper at age twenty-five that says “Master” on it. Alice Neel was a master. Those young painters in the fancy SoHo galleries were just kids.

If you really want to make ART – with a capital A – you have to let go of your hunger for praise. You’re have to reach into this search for something where you don’t even know what you’re looking for. You’re looking and looking and finally, maybe, something comes through. And yes, you facilitated it, but you didn’t exactly make it, you were just a kind of a conduit.

Joseph Campbell talked about this. I wish I could remember the exact quote, but there’s a great little vignette in that PBS series of interviews between Campbell and Bill Moyers from the 1980s. Do you remember that – where he talks about how art works?

LG: I do, but it’s been a while so I don’t remember too much.

Christopher Benson:

There’s a moment there where Campbell is talking about the role of the Shaman in pre-agricultural, hunter-gatherer societies. These were oddballs and mystics — men and women both — who went out into the woods or the desert and tapped into the big woo: to nature, the universe, the Brahman, God, the Tao, whatever you want to call it. Then they’d come back to the tribe and share what they’d seen. They didn’t invent what they found out there, they were just an amp and a set of speakers for it. Campbell equated the Shamanism of the hunter-gatherer cultures to the modern art he’d known in the first half of the 20th century. In effect, what he said was that the artist is this person who opens themselves up to that bigger thing — call it whatever you want — and that thing then “speaks through them.”

That, to me is where art comes from. It can take a million different shapes and styles; it can use any media; it can talk about spirituality or philosophy or politics, or just pure aesthetics. But if it doesn’t go through the struggle to find that bigger non-egocentric voice, then it just isn’t art as far as I’m concerned. It’s something else. And I think we are drowning in a sea of “something else” right now.

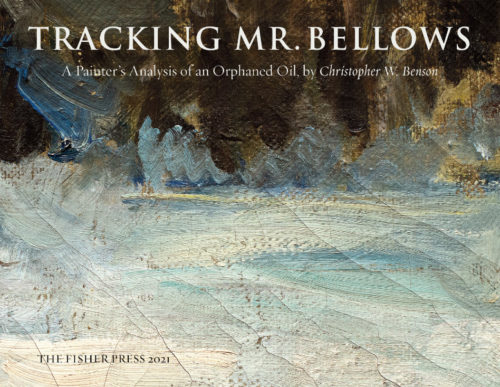

LG: You wrote the book Tracking Mr. Bellows: A Painter’s Analysis of an Orphaned Oil.

Can you tell us something about this book and where it’s available?

Christopher Benson:

Tracking Mr. Bellows is no longer available for sale. I’ve pretty much sold out that little edition. A couple of years ago I saw an old oil painting hanging on a friend’s wall in Vermont; it was in a photo he’d posted on Facebook. I recognized it immediately as an early 20th-century American piece, and probably by one of the “Ashcan School” painters. It just had that distinctive signature and style that was so unique to that group. It was also clearly made by somebody good, not just a derivative thing made “in the style of” by some student or Sunday painting amateur. It had all the confidence and the raw, original gesture of a “Real McCoy.” I wrote and asked my friend what it was and where he’d found it. He didn’t know much. His dad had bought it at an art and antique gallery in Pennsylvania near Chadds Ford in the 1970s or 80s. There was no signature on the thing and no recorded provenance prior to the antique guy who had long since closed up shop and passed on.

My friend sent me photos of the painting and I started examining them carefully to try and figure out who might have made it. Once I saw some hi-res images of it, I started to feel pretty strongly that George Bellows had probably painted it. I made some forays out to dealers and scholars and curators who knew Bellows work, but none would talk to me — they were all pretty dismissive and wouldn’t even agree to look at the thing. I realized pretty quickly that however much they might think they know about that painter, they couldn’t possibly know about him in the same way that another serious painter — working in a related style — could know and see. I ended up trading one of my seascapes for the putative “Bellows,” and once I had it in my studio, I became even more convinced that he had made it. So I wrote a book about that: about what exactly I was seeing that persuaded me that George Bellows made this picture. It was a fun project, and the book is actually much more about oil painting itself than it is about that particular painter. We didn’t print too many copies initially, just 100. But I plan to do a bigger second edition at some point.

LG: Can you tell us a little about the book you mentioned earlier – Art in the Making?

Christopher Benson:

That one is a much bigger and more complex publication than the little Bellows book. It’s a project that I put together and designed, and which my brother Nick Benson and I initially conceived and are co-publishing. Nick is the current owner/director of our family’s 300+-year-old stone carving shop in Rhode Island. He’s a 2010 MacArthur fellow, and an outstanding artisan and artist. So this is a joint Fisher Press and John Stevens Shop project.

We have a large and very diverse group of contributing essayists in the collection: there are performers, painters, sculptors, wood engravers, craftspeople, photographers, poets, ceramicists, blacksmiths, woodworkers, illustrators, chefs – you name it. We even have a chapter devoted to Conceptual art. The essays are short and personal, and pretty non-academic, non art-speaky narratives. We really wanted to give the reader an opportunity to hear from makers and the artists themselves.

Look – I’m something of a notorious crank among the family members, friends and colleagues who know me. I’ll cop to that comfortably enough. It’s pretty clear, I’m sure, from this interview that I’ve spent much of my life looking askance at what’s been going on in art all through the years I’ve been involved with it. Over the past twenty years, I’ve also been writing a lot of critical essays and other articles about all of that. My friends roll their eyes and say “There he goes.” But I think somebody needs to do this, to question habits that become accepted and ingrained too easily. Besides, At the end of the day, I genuinely love my fellow artists. It’s the institutions I’m not so crazy about. The words art and institution just don’t belong in the same sentence as far as I’m concerned.

I actually like, and am open to, most of the things that artists are trying to do these days, and I really have no prejudice about the different kinds of art that people want to make. I’m just very particular about who does and doesn’t do a given thing well. I’m also — as I’ve said above — quite skeptical about the motives behind a lot of contemporary art that seems deliberately made to win fame and riches in the market. That’s not the same as getting respect and making a living. We all have to make a living, but I think you gotta figure out how to make the good stuff — and to live the artist’s life, the challenges of which foster real exploration and growth — before you start calculating how to win critical acclaim. If you do do that, from that point on, it’s always going to be a struggle between success and comfort on the one hand, and the positive evolution of your art on the other, and those things aren’t necessarily compatible.

It’s weird being an artist, you know? It’s such a strange thing to do. You kind of have to be out of your mind to take it on, so I appreciate and am prepared to be supportive of anybody who takes that on sincerely and in their own way.

LG: As you’ve said, part of your income is made as an editions printer, and you also write, design and publish books about art. Your Pictures and Windows book was amazing — the quality of the prints and writing everything about it was excellent.

The book can be obtained here. https://www.thefisherpress.com/books-for-sale

Christopher Benson:

Thanks! The books and the painting are all of a piece to me. They’re different disciplines that nonetheless talk to and inform one another. Each also provides some respite from the other when I need it. They also both make me a decent living. As I’ve said, there’s no way I could survive financially as a high school or college art teacher. Even with my wife working full time as an educator with a doctorate — which she does — we still couldn’t get by.

Besides, as I said earlier, I can’t stand having other people tell me what to do, and I really don’t like it when it’s an institution doing the telling. I’ve been self-employed now since 1985, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I think a lot of my skepticism about and resistance to the art world is about that. As I’ve discussed already at length, art has become very institutionalized and proscriptive in my lifetime. The academic institutions and experts have gradually reasserted their presumed right to tell us artists what we should and shouldn’t do. But I’ve always found it pretty ironic that the avant-garde movements of Modernism, which were launched as a rejection of the old French Academie and Salon, finally led to the establishment of a new avant-garde-oriented academy system in American colleges and universities.

I prefer the world I was born into as the son of a couple of RISD undergrads in 1960, before the big market takeover. That community was just this a ragtag crowd, living in lofts or barns, eating beans and rice, and basically living to make this weird art stuff. They were actually turning their backs on the careerism and money-obsessions of the corporate Mad Men era, and the art colleges of that period were just places you went to in order to acquire your tools and skills. There was no crazy speculative art market luring young artists with Warhol’s promise of fame, and NOBODY expected to make money at it! It was just a bunch of weirdos making all this cool stuff that hardly anybody understood, and which even fewer people paid any attention to.

I still kinda live in that world, and it suits me just fine.

A wonderful and very readable talk. A rant at times, but why not? The rant reminds me of wonderful rants I remember from an artworld long ago and far away; those artists from the seventies and earlier in New York and elsewhere who did love to carry on. This is the world of nonacademic and noncommercial art and artists Christopher refers to with admiration. Paul Georges comes to mind. Sidney Tillim. And of course, Alice Neel. Fairfield Porter was certainly no academic, and he was initially scorned by the critical and museum world Christopher excoriates. I love the more figurative paintings especially. Great stuff. Thanks.

This interview covered so much personal and professional information, I needed to read in in chapter format. Thanks to C.B. for being so accessible and for your insightful questions.

The assessment of Albers made me laugh out loud- I completely agree..

I’ll be looking for Art In the Making.

Thanks for presenting this post.

Brilliant.

Wonderful paintings, Christopher, and it’s also refreshing to hear your critique of the contemporary “academy” and careerism that control painting today. Big art institutions want to be be both the powers-that-be that dictate value in culture AND the creative rebels, and you can’t have it both ways. Like you, I’m grateful that I went to art school before elitism took over, and we could still be taught by painters who focussed on observation, experimentation, and learning from the masters of our craft.