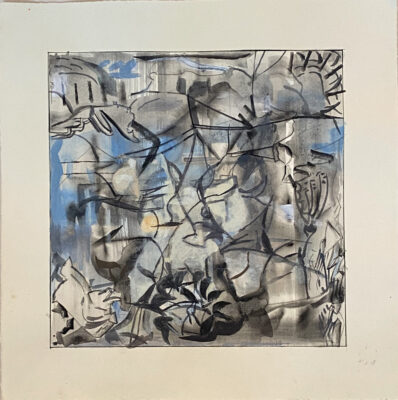

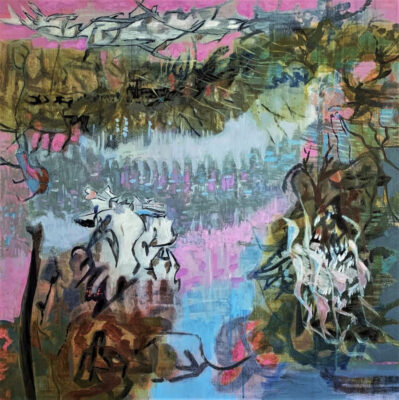

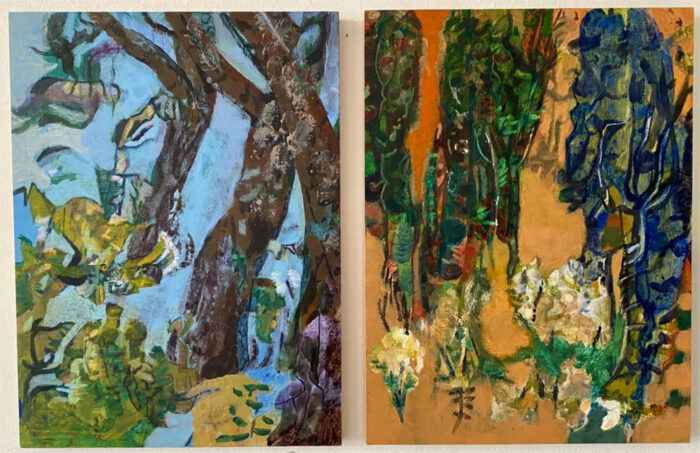

I’m pleased to present an interview with Cathy Diamond, an NYC-based painter whose abstract paintings have evolved from a long involvement in responding to nature. Her work offers a unique narrative that draws from the fluidity and interconnectedness of shapes and sensations found in nature. “The sounds of wind and birds have always utterly entranced me.” Diamond shares in this interview, “Add to this the almost cellular feeling that the scene is all in a state of growth. These connective tissues open up the space for me to become a part of this through automatic and rhythmic drawing. The machinations of the trees, insects, and birds lend themselves to metaphors for aliveness, movement, fragility, endurance, and connectivity.”

Jorge S. Arango wrote in a review in The Portland Press Herald,

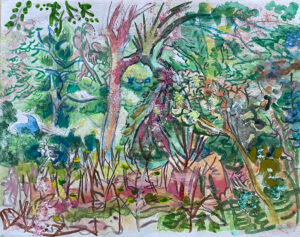

Diamond’s works “are really a hybrid of drawing and painting, and their surfaces buzz, sizzle and quiver with a feverish energy. They are clearly landscapes, but abstracted in ways that capture nature’s ability to constantly morph and evolve. In this way, they viscerally convey a kind of aggressive fecundity of nature…Diamond’s works are breathtakingly gorgeous and just a little scary in their suggestion of nature’s uncontrollable, untamable power.”

Cathy Diamond’s prolific career spans three decades exhibiting primarily in New York City. Recent highlights include exhibitions at Lockwood Gallery in Kingston, NY, Radiator Arts, NYC, Alice Gauvin Gallery in Portland, Maine, and curated shows at Green Door Gallery in Brooklyn. Her work has been featured in solo and two-person shows at Sideshow Gallery, Andre Zarre, Farrell Pollock Fine Art, Valentine Gallery, and The Painting Center, among others. Diamond’s works on paper have been showcased at international print fairs including Miami Basel, Cleveland Museum of Art, Park Avenue Armory, and Boston Print Fair, represented by Van-Straaten Gallery and Oehme Graphics. She has curated exhibitions at Joyce Goldstein Gallery and Supermoon Art Space and has been featured in publications such as Artspiel, Two Coats of Paint, and more. Diamond teaches Painting and Drawing at Borough of Manhattan Community College and received her art education at The University of Michigan and The New York Studio School.

Larry Groff: What were your early years like, and when did you decide to become a painter?

Cathy Diamond: I started making crafts in middle school at after-school art lessons in the basement studio of a local teacher whom I liked. The various projects, from firing glass bead jewelry to copying national geographic covers in watercolor to building and painting papier-mache animals, kept us busy and fired up our imaginations. In high school, I had a strong artistic outlet in the art department, with a dedicated teacher encouraging us to aim high. It was a natural decision to apply to colleges for fine arts.

LG: Please share something about your art school experience, particularly how it influenced your artistic development.

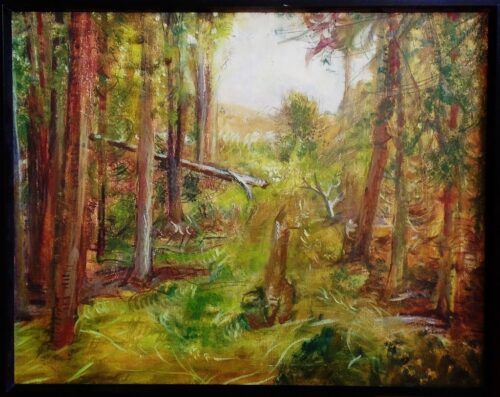

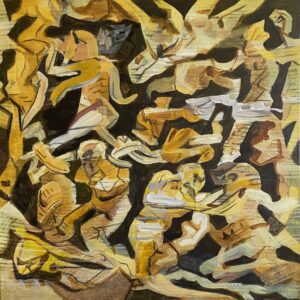

Cathy Diamond: At The University of Michigan, I gained three years of practice in building abstract paintings from relationships of color areas while experimenting with various brushwork approaches. Artists looked at were Diebenkorn, Karel Appel, Nicolas de Staal, Cezanne, and the Post-Impressionists. I continued my studies a few years later at the New York Studio School, where I attacked figure drawing. This was a challenge, but it paid off. I started there by painting figure compositions influenced by Vuillard and Lautrec, working from oil pastels made in bars, cafes, and coffee shops. While working with Nick Carone, this evolved into a more muscular, rhythmic drawing and painting from Michelangelo to De Kooning. I was also introduced to the abstract surrealist drawings of Gorky as well as Matta, who was a close friend of Nick’s. There was an immediate history of modernism there, and so many alumni stayed in NYC, so there’s a strong connection there. I think influences from the University of Michigan and New York Studio School worked on me throughout my twenties and early thirties. I continued studying independently by returning to figuration for a while – I loved portrait drawing and painting and did commissions professionally for years. Later, I spent summers working directly from nature in oils (out in pastures with a French easel). This led to residencies and to a deeper and deeper connection to nature. Ultimately, going from plein-air to invention and back is an essential duality.

LG: Did your identical twin, Carol Diamond, influence your artistic journey?

Cathy Diamond: Carol and I were willing duos for these early lessons and continued to be so in a natural flow into the arts. She always encouraged, and in many cases led the way toward, art-making as a way of life. Where we’ve come from and how we relate now has allowed us to share our aesthetic growth—our sensibilities connect while being utterly specific to our own paths.

LG: Did you navigate this journey together with your twin sister?

Cathy Diamond: In the earlier years after school, we dove into developing these separate paths; my works centered around larger figurative and abstract compositions, while Carol’s work homed in on highly personal portraits, still lifes, and cityscapes. After moving to Williamsburg, my paintings started to reflect my urban city view, so I took a break from line and figuration to work on color and geometry. Interestingly, though, Carol and I finally made a cross-over in our late 30s and early 40s when she evolved away from perceptual work toward abstraction, and I moved toward more directly perceptual works from city views (the Williamsburg Bridge over the East River) and from nature scenes at rural retreats. I worked this way and then moved back toward abstraction. Carol and I have organically settled into the connection to nature (me) vs the urban world (her), which has been a focus in our works for years.

LG: Nature is pivotal in your abstract works, serving as inspiration and subject matter. How do you translate something unseen into something visual? When you think about the ‘unseen energies’ or ‘erratic flight trails’ of birds and insects that you discussed previously, how does that enter the visual language of your paintings?

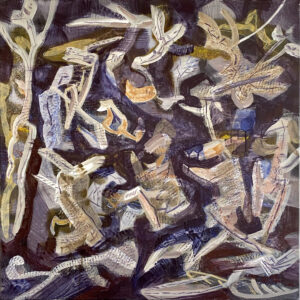

Cathy Diamond: The sounds of wind and birds have always utterly entranced me. Add to this the almost cellular feeling that the scene is all in a state of growth. These connective tissues open up the space for me to become a part of this through automatic and rhythmic drawing. The machinations of the trees, insects, and birds lend themselves to metaphors for aliveness, movement, fragility, endurance, and connectivity. There’s some metaphor in the tiny unseen sparrow’s throat amplifying an enormous Sycamore. I paint small works on paper in nature with the goal of capturing as many bits of these multiple movements as I can. I bring these studies back to NYC, and it is through reliving these ‘woods encounters’ that they evolve or morph into private animations. I’m trying to weave together pieces of it to make a picture that can come alive on its own terms.

LG: Memory seems important to your creative process, especially regarding landscapes. What kind of memories best translate into abstract forms for you?

Cathy Diamond: The more I feel inside the woods, the more all the overlapping elements tend toward abstract space and form. The times I’ve spent in the deeper woods live in my imagination as these embracing, soaring, ominous, yet entrancing places that I can only capture a tiny piece of. I also naturally see abstractly; that is, I’m more interested in creating new tree-bird hybrids than in depicting recognizable, identifiable, known forms.

Some recurring themes make up my internal pictures, most of which involve a slightly dangerous swath of woods, either caught up in the undergrowth or on a borderline looking in. Another is that quintessential feeling of being on a path narrowing into the woods, this metaphor for time, movement, choices, and self. The works are meant to draw you into a mysterious place yet also have a sense of safe return, finding an opening to the light. Another early source for this relates to childhood experiences at overnight camp, including mythical bonfires surrounded by dark trees and also the strips of woods in the neighborhood where I grew up that had their way of beckoning us from our landscaped lawns to meet within their small topographies. Childhood was not without a darker side, though, as I had recurring nightmares about hiding in those woods from a bogeyman and Little Red Riding Hood’s wolf attacking my best friend!

LG: Your artist statement mentions being inspired by ‘forms and sensations derived in Nature.’ Could you share how non-visual sensations, such as smells, textures, or emotions evoked by the natural environment, influence your work’s color, texture, and form choice? Could you provide examples of how a specific sensation or emotional response to nature has directly inspired a piece or series of your art?

Cathy Diamond: I came to ‘texture’ later in life – I think I felt it was this extraneous effect. To think that the grandness of nature is created by a seemingly infinite number of very small occurrences layered on top of each other is like life in society or any complex system of relationships. The repeating rhythms allow for these musical riffs of lines and forms, as well as dance rhythms/arabesques. Texture can also create the enveloping feeling of air itself, which I try to achieve through many layers of transparent paint. As for sound, when it’s supremely quiet in nature, it’s the wind tunneling through paths that speaks for all of it, the whole breadth of it all, or a rainstorm pattering through the night that allows all of the woods as one to bathe and receive it. For me, being in nature is so much more than depicting light and dark forms; it is about depth, continuity, and belonging.

LG: What other painters have you looked to for inspiration about painting the non-visual?

Cathy Diamond: Abstraction connected to Kandinsky, Andre Masson, Miro, and Gorky is my wheelhouse. In each case, traditional form painting led to more weightlessness while retaining a real specificity of the drawing elements. The space between their forms, which holds them at bay while simultaneously drawing them together, usually composed without a horizon, gives the linear forms a rhythmic connectivity. There’s a lyrical animation and imagery that draws from the subconscious that speaks to me. I also came to Burchfield later in life – he comes from my home state of Ohio- and brings that spiritual echoing around his trees that I respond to, as well as his expansive use of watercolor. Picasso, on the more figurative side, has been an influence from the beginning. I also love all the great landscape painters – Constable, Theodore Rousseau, George Inness, Thomas Cole, Brueghel, and many others give me deep pleasure.

LG: The transformation of botanical into biomorphic and abstract forms seems important to your work. What attracts you to this concern?

Cathy Diamond: In college, I minored in textile design and worked in this field for a while in my twenties. Flat, quirky shapes that were part insect/plant became a referential abstraction I pursued even then when making patterns. Later, after I moved away from the figure, I saw trees and bushes as figurative stand-ins. I find them as animated as people are – upright and proud, frail and hunched, reaching out, starting simple and becoming increasingly complex. While it’s important to create ‘middle-ground’ space in a more traditional landscape space, I came from a tradition of seeing the picture plane as a kind of up-close lattice against a suspended background, skipping the space of the middle-ground, or coming to it, anyway, via a kind of ‘metaphysical’ suspended plane. I also worked to combine the two approaches, that is to suggest a middle-ground while also maintaining a compressed frontality.

LG: You’ve described the line as ‘the essential ingredient that inhabits my imagination,’ leading to the creation of branch-like figures, crazy-figurative hybrids, and representations of unseen energy. Considering this pivotal role of the line, could you walk us through your process of drawing these lines? Since you’re not ‘mapping’ a seen place or thing, how do you decide the veracity of your line?

Cathy Diamond: I often work in the landscape, so it is those interactions in the drawings or paintings on paper that I get inspiration from for larger paintings. They do feel like a kind of map of these places, which get transposed further by working from memory into a new arena. As for the line, works done from winter’s bare trees, for instance, comprise this moody study of linear gestures of incredible structures in contrast to the repetitive, smaller mark-making of summer textures. Later in the studio, I paint into the negative areas to push forward, creating new shapes while developing the atmosphere. It goes back and forth from what the line is becoming to how the layers of paint are suggesting or becoming an atmospheric place. I do feel that line, by which I mean drawing, is such a personal means of inventing forms and is such a carrier of rhythm that I’ve been guided for years to weave it more primally into painting.

LG: Given your exploration of non-visual sensations and the abstract representation of nature’s forms and emotions, how do you feel about viewers who approach your work with a focus on identifying specific forms and judge the painting based on how well these forms align with their own perceptions of reality?

Cathy Diamond: I want my works to suggest a place – any place – that a viewer can move through and see more and more paths to take. Some people see the abstract elements and are less interested in finding a narrative or figure to place. Either way, I’m very happy for multiple readings as my works are suggestive and open to various associations. I’m part abstract surrealist and part nature-based – readings of my paintings can span either territory. But, everyone has SOME connection to nature, so they associate through that raw connection to living animation.

LG: Please say something about how you start a painting and what is generally involved in your process.

Cathy Diamond: I generally start by looking through my works on paper, plus many photos I take of places I’ve been, as well as details of plants and flowers on my local walks in Queens. I use them as references, jumping off points. Often, when starting paintings, I tone the white canvas or panel a color, then start drawing with paint in an open calligraphic way. As we all do, we have brushes that do different things, and for me, the quality of the gesture is important and intuitive. I’m working with water-based paints, so sometimes, after I’ve got an active drawing, I’ll mix a negative space color, either lighter or darker, and start cutting in shapes. Then I sit with it, as what the ‘story’ is about is something I will see over time.

LG: You enjoy experimenting with new methods, materials, pigments, and collages. What do these experiments do for you, and how do they affect your work?

Cathy Diamond: One of the biggest bonuses of switching from oil paint to water-based paint (though I have since returned to oils) was that my works on paper and canvas were becoming intertwined – I started mounting my paper works to panels to become paintings in their own right. Paper is ultimately my favorite surface. When you spray water into the paper and to the marks themselves, the paint and line do wonderful things. I use Guerra pigments with gel mediums, Golden and Lukas acrylics, and different modeling pastes.

I do make some collages from ripped pieces of past paintings on paper – I work on the collages during different transitional periods – they let me focus on shape, composition and chance.

LG: What books have you read recently that significantly impacted you?

Cathy Diamond: I’ve mostly been reading and listening to journalism related to the war in Israel-Gaza, as I’m Jewish, and this has been quite a reckoning. There are so many voices and interpretations about history that it’s been a deep learning curve and entirely overtook my ‘reading’ time. This said, I’m starting 9th St. Women, which I’m already savoring.

LG: We’re all living in very crazy, unstable times. How does this impact your artmaking process and the themes you explore? How do you balance personal expression and artistic sensibilities with the urge to respond to or reflect on these global concerns?

Cathy Diamond: The crisis in Israel impacted my work in a way I never would have expected, as generally, my internal imaginative world is connected to changing seasons more than changing events. Immediately after 10/7, I began a series of figurative works for several months, with no trees or botanicals and no autumn palette, just gold tones and black. I needed to feel what was going on regarding loss and displacement in this pictorial way. In part, I revisited earlier figurative works while inventing new spaces and figures. I concluded this group around April, having segued back to the landscape, but I hope I’m not done with these.

During the pandemic, my work changed too – I worked on paintings on paper that seemed to be expressions of our societal and personal fragility. They were concerned just with linear movements of brushwork, somewhat figurative, and all about fragility and time, as they were slow and involved. They came from a grouping of unfinished paintings on paper, where I kept editing down dark forms with a light, mutable ground color until the forms got thinner and frailer, then added other gestural marks. In both cases, the communal loss strongly filtered into my works. It’s hard to say how future events might affect me creatively, but I suspect they will. In the short term, I’ve already enjoyed two visits this summer to rural locations to paint and plan on more to come. I’m actually in the midst of a project of working in to several unresolved works on paper and canvas to find their deeper voices. This has been a beneficial and interesting process.

I would like to thank you, Larry, for this terrific opportunity to reflect and take stock of threads and themes over my career from its very beginnings. I’m thankful for your interest in my work.

Leave a Reply