I’ve long been intrigued by Carol Heft’s drawings and paintings that she frequently posts to Facebook. Many of her landscape drawings are spontaneous creations that begin from rapid observations of tree configurations seen out a bus window on her long ride to work from NYC to Allentown, PA. I’m particularly intrigued by the relaxed way she traverses the borderlines of abstraction and representation–observation and imagination; it feels as natural as breathing in and out. Her abstractions are imaginary worlds lyrically filled with light, atmosphere and life.

Heft has several solo shows at Blue Mountain Gallery in NYC where she is a gallery artist. She has had solo exhibitions at Dakota State University, Mattera, Italy, University of South Carolina and LaCuca Gallery in Easton, PA. and Fairleigh Dickinson University among others. She has also been represented by the First Gallery Grassina in Florence, Italy. She attended the Madison Art School where she studied with Robert Brackman, N.A., studied at the Rhode Island School of Design where she received her B.F.A and Hunter College for her M.Ed. She teaches at the Muhlenberg College, and Cedar Crest College, in Allentown PA, and St. Joseph’s College in Brooklyn, New York. She currently lives and works in New York.

Her recently launched website can be viewed at carolheft.com

I’m delighted that she agreed to this email interview and want to thank her for her time and generosity in sharing her story.

Larry Groff: What was art school like for you?

Carol Heft: I started studying when I was about 12 years old. My first painting teacher, Anne Tuttle, brought me to a school in Madison Connecticut where Robert Brackman did a summer residency program. Brackman was an American master of traditional academic painting, who taught at the Art Students League in New York. I was his studio monitor for the next three summers, and made lunches for the students, mostly adults from his New York class. I was very lucky to have had that experience at such a young age. A follower of Eakins and Bellows, Brackman’s teaching style included demonstrations. Watching him paint was like watching a great dancer, inspiring and beautiful. My high school had a lithography press and an intaglio press, and my teacher and mentor, Gary Stanton, encouraged me. I always loved to draw and paint, and when I started learning about printmaking, I thought I had found my calling. I was a printmaker. I loved it. Later, when I went to the Rhode Island School of Design, I returned to painting under the tutelage of Leland Bell, Louisa Chase, Lorna Ritz, Victor Lara and other great teachers and classmates. In spite of my difficult passage from adolescence to adulthood, which included some personal trauma, I liked school very much. I have always loved being in an environment dedicated to learning and study.

LG: What were your first few years like after getting out of school?

CH: I moved to New York in 1976 after I graduated from RISD. I moved into a loft on the Bowery and went to meetings of a group of artists known as the “Alliance of Figurative Artists” or the “figgies” as Lisa Chase called them. I painted and drank a lot as I clumsily negotiated my way through a failed marriage, and various survival jobs. Finally, when I was about thirty, I came to a turning point in my life; a spiritual awakening. It seemed to me that I had been in a daze for most of the past decade, and now, with eyes open, I was able to look at my work with some sense of humility and understanding of what was (and was not) important to me.

LG: What artists do you most often draw inspiration from in your work?

CH: Too many to mention here. The Paleolithic cave artists, Paul Klee, Pieter Breughel, Rembrandt, Kandinsky, Caravaggio, Tiepolo, Berthe Morisol, Mary Cassatt, deKooning, and some contemporaries: Karen Kappke, Ginny Greyson, Heidi Rosin, Vered Gerstenkorn, Francois Dupris, Jean Pierre Bourquin, and Martin Campos, to name a few.

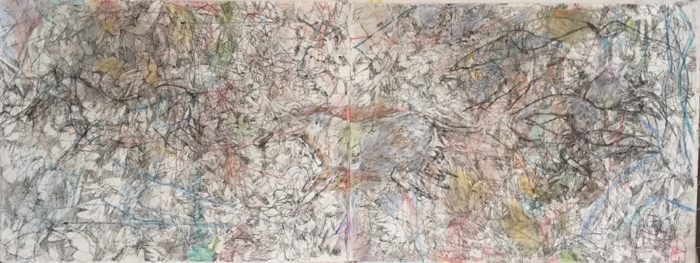

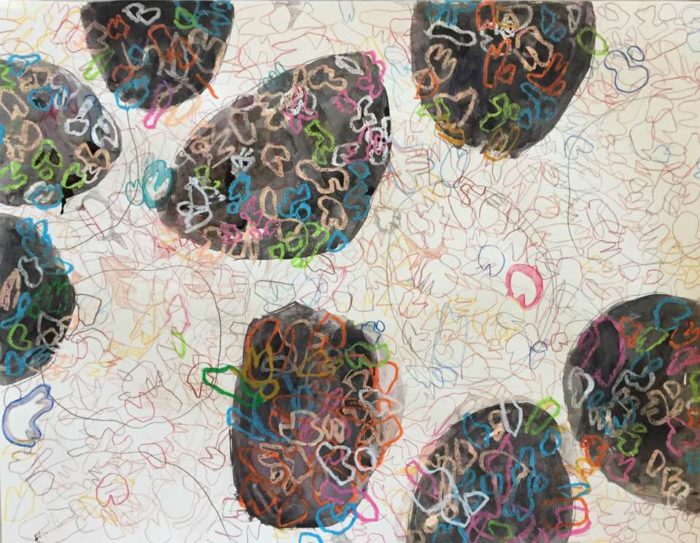

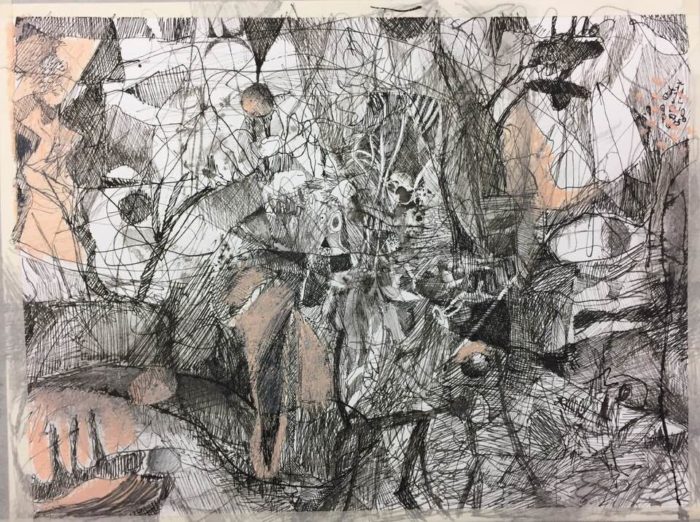

Incident #19, Homage to the Masters of Lascaux, Altamira and Pech-Merle,

ink and wash, chalk, and colored pencil on paper Diptych, two sheets, full size 18 x 48 inches,

5.28.18

LG: How do you start a new painting? Please tell us something about how you go about making your art?

CH: When working from observation, I usually follow the traditional approach of working out a composition with charcoal (Brackman used to say that composition was the most important part of the painting; “no matter how badly it’s painted, if the composition is good it will be worth looking at, and no matter how ‘well’ it is painted, if the composition falls apart, the painting falls apart.” Next I work up a chiaroscuro underpainting with yellow ochre, still composing, establishing shadow patterns and tonal descriptions. I think that is my favorite part. You can see the painting, its essence, its orchestration of shapes and movement in this phase. It is the most beautiful to me. The drawing disappears, and there is a tonal impression of what is possible left on the canvas.

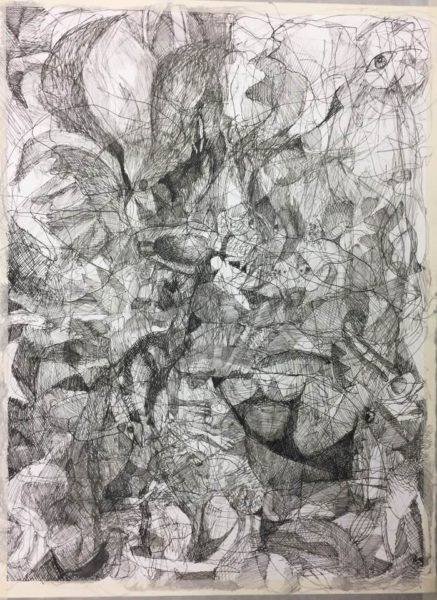

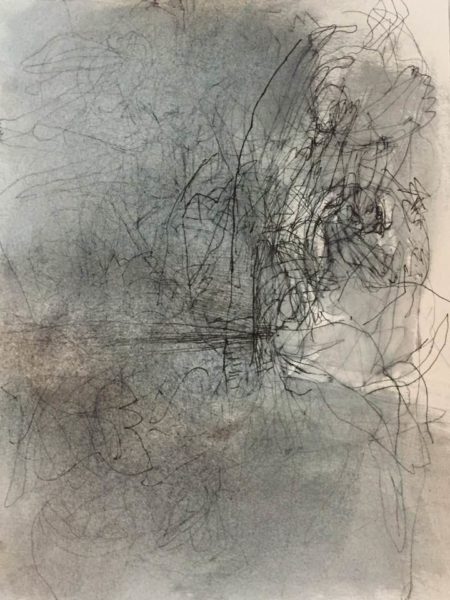

When I am not working from observation, the first step of looking at the subject is replaced by making marks. The subject is either on the paper already, and I have to find it, or it is in my head or heart, trying to get onto the paper through my hands. I usually make a few marks and then look at them, and go back and forth like this until I feel I can’t learn any more from the work. Then I stop. It’s very different than finishing a portrait, for example, where it is often clear when the last stroke is applied, that no more need be done, and any more would be counterproductive.

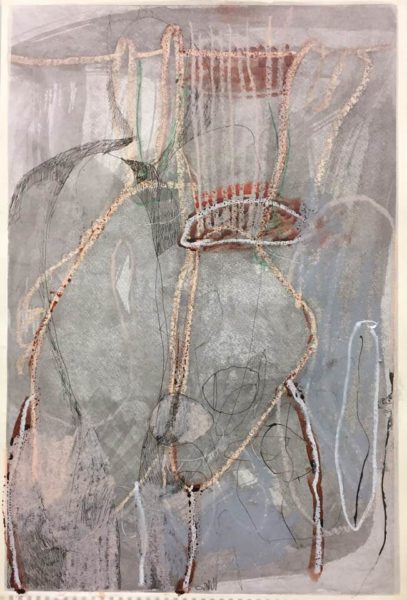

Incident #21 or On the Surface, pencil, pen and ink, oil pastel and watercolor on watercolor paper, 8 1/2 x 11 inches 5.23.18

LG: What role does your mark-making play with your work? Is this a way to access or deny your mood or is it more exploratory investigations of formal art concerns – are there connections between these two things?

CH: I don’t really think my mood plays much of a role in my work. Self-expression is not necessarily connected to a person’s affect. As a professional artist, I think of my work as an ongoing organic series of events in which I participate, but do not entirely direct. The decisions I make while painting or drawing are intuitive. It is only afterward, during reflection, that I begin to understand what those decisions mean, how marks, tone, value, texture, color, how they all work together to create a world, a universe really, with its own parameters.

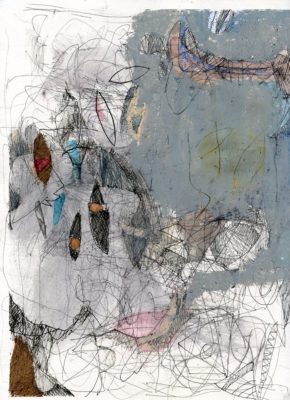

Automatic Drawing #11, watercolor, pen and ink, and oil pastel on watercolor paper, 9 x 12 inches, 5.7.18

LG: I’ve read where you’ve talked about your work being an interactive process. What helps you to better listen to what your work might be saying?

CH: Spending time reflecting on the impact of what I am doing has had or will have on the work. It’s such an enigma, two dimensional art. It’s flat, and you see it in an instant, but it exists in time. It is made in time, can be looked at over a period of time and has visual space and movement, all with temporal analogies. Sometimes I try to visualize a specific change or revision in a piece, but often I need to physically make the change in order to really understand the impact it has on the total. The whole is different than the sum of its parts. Photographing a drawing or painting and putting it in a program like Photoshop is helpful, you can change colors and move things around instantly. It speeds up the thinking process, but to me, it is not a substitute for the physical pleasure of getting paint and glue on your hands and feeling it move from the brush to the paper or canvas.

LG: What things might you consider when you start re-working a piece you hadn’t looked at for some time?

CH: When I go back to a piece after many weeks or months, I see it differently, it gives me a chance to integrate ideas that span a period of time, creating temporal layers, while keeping my eye on the unity that is intrinsic to the world of that particular work.

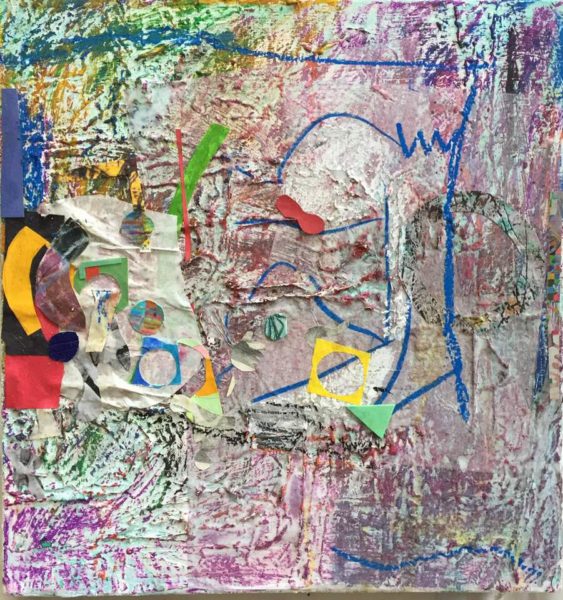

Visit to the the Veterinary Physician’s Office, pen and ink and watercolor and oil pastel on watercolor paper, 11 x 15 inches, 4.29.18

LG: Many people, especially those with limited art backgrounds, tend to judge representational art by its fidelity to what they think something appears to look like, its photographic likeness or if it follows expected visual conventions. What are some similar ways people wrongly judge abstract works and how would you try to dissuade them?

CH: I think helping people develop an open mind about art is a critical aspect of art education. One of the things I am grateful for having had the opportunity to teach art history is that it forced me to look at and study work that I may have overlooked or dismissed otherwise. This is compatible with having good taste and good judgement. With my traditional academic background (Brackman) it was hard for me to look at non-representational art. For years I could not see Matisse or Leger, or even Picasso. It wasn’t until I had teachers like Lisa Chase, Judy Pfaff and Lorna Ritz, who helped me see beyond the limited scope of what I had been taught. I never judged work by its fidelity to the subject though. In fact, I always thought “realism” was silly. It was painting the surface of something, rather than finding its essential qualities. A great photographer knows the difference between “taking pictures” and composing with the camera. A painter has the same kind of aesthetic choices to make with his or her eye, brush, and heart.

I think of most of my work as figurative and nonobjective at the same time. The figure ground relationship fascinates me in and of itself, but also as it serves the subject. Relationships between shapes, colors, line, all play a role in how the work is experienced. It takes an open mind and engaged viewer to appreciate any work of art, and often these qualities are a function of education and willingness to see things from diverse perspectives.

LG: Your drawings of nature, especially trees and such, often seem to have a Rembrandt-esque tonal naturalistic manner. Many of your other drawings seem more abstracted, intuitive and free-form. What can you say about these different approaches to drawing?

CH: I’m not sure the approach is so different as the intent. Drawing from observation, even the landscape drawings I have done looking out the window of a moving bus, are conduits that allow me to appreciate the beauty of nature, the magnificent myriad of line that exists in a group of trees, translated into and from the marks themselves, which are also beautiful. That is the connection. The whole is different than the sum of its parts, but the parts are vital to the cohesive meaning of the whole. This is true regardless of subject matter, at least in my work.

LG: You clearly enjoy exploring many modes and means of working. How important to you is having a consistent or unified body of work in a show?

CH: Consistency and point of view is critical to a successfully designed exhibition. Whenever my work is exhibited, I am conscious of this and it is a primary concern. I often ask Nancy Prusinowski, one of my favorite artists and colleagues to help me hang a show. You need someone who can help you resist hanging your favorite paintings from a particular body of work. Some of these may have to be sacrificed in order for the whole room to have the impact you want- with individual pieces not competing with each other, having enough room to be seen, and at the same time not being swallowed up by the wall (unless that is the intent).

As far as my work and exploration goes, I am very happy that I allow myself to follow my interests and have not tried to pigeonhole myself into a stylized rut. I am much more concerned about what I am learning than what other people think of what I do.

LG: Do you ever wish to convey any non-visual components to your work; such as feelings about spirituality, politics or emotional concerns?

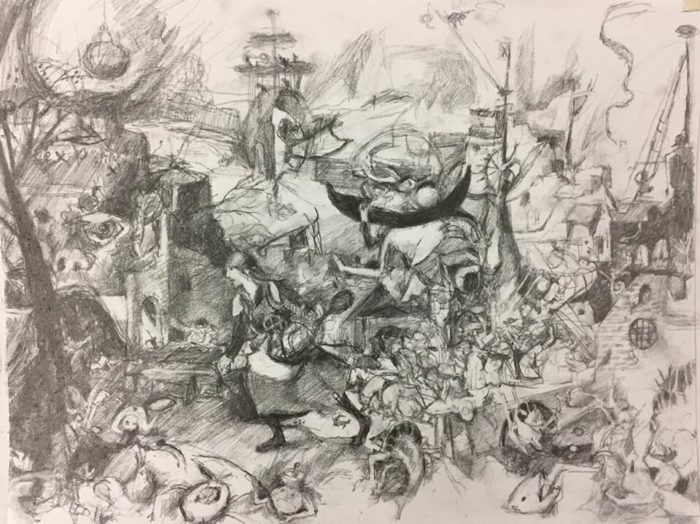

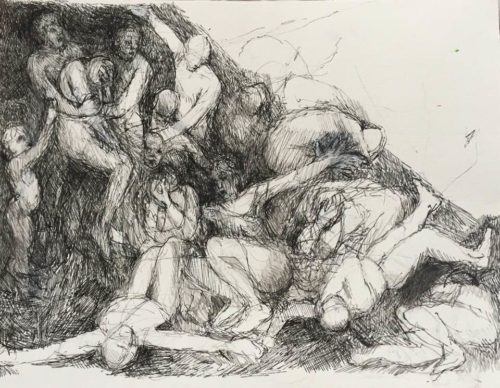

CH: I think most art is a visual language that speaks of love, death, magic, beauty, tragedy, music, fear, and every other human feeling or endeavor. I don’t consider my work “social comment” art, but sometimes I am moved by current events to do work that is political in nature. I am currently working on a series entitled “War” that is inspired by Goya’s Disasters of War etchings, and Kathe Kollwitz drawings and prints.

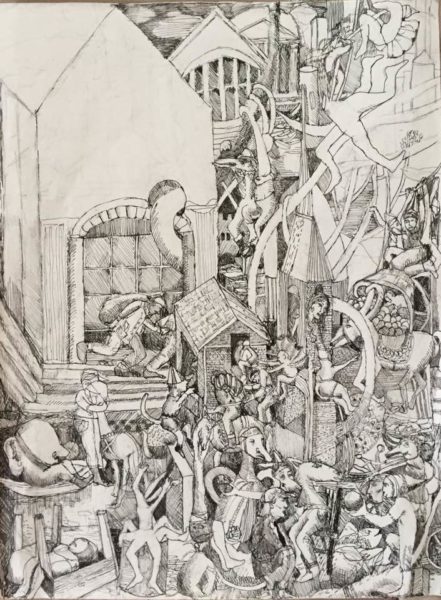

I have also parodied the present administration in a drawing I call “moving into the white house” a la Breughel.

LG: When something feels off with something you’re working on – what do you do?

CH: I usually keep working on it until I like it, then I stop when there is nothing more to learn from it.

LG: What does taking risks with your work mean to you?

CH: Every time you put a mark on a blank surface you are taking a risk. It’s the most exciting and exhilarating feeling in the world. To me taking risks means being willing to sacrifice what I know I can do for what I don’t yet know is possible.

Imaginary Landscape with Real Trees #4, 10 x 14 inches ink and watercolor on watercolor paper 5.13.18

LG: It’s not uncommon to run into painters whose self-esteem tends to vacillate between feeling high or feeling low–with regard to their work. Sometimes these feelings bring disaster while in other situations it creates great art. What advice would you offer someone with a problem like this who sought your advice?

CH: Self-esteem plays a role in the life of an artist in the same way it does in any other profession. I believe I have a gift. I can draw. I did not give myself this gift, but I cherish it and am grateful for it. Self-esteem and humility, in that sense, go hand in hand. Some people can sing, or are great mathematicians, poets, musicians scholars, teachers, statesmen. My work is an expression of how I see the world from the inside, how I intuitively organize what I see. Only from my inside, since I don’t know what it is like to be anyone else. I have had glimpses of the world as seen by other artists through their work. In that sense, making art is sharing one’s gift, and act of generosity. Recognizing a gift and feeling it a privilege and an obligation to use it generates and is generated by faith.

LG: Do you ever worry about people not being able to really see your artwork due to shortened attention spans from the distractions of social media or other online activities?

CH: Not really. I have no control over that. People who are supposed to see my work see it, just as whoever is reading this is supposed to be reading it. Some will and some won’t. I’m still going to continue making art as long as it nourishes my soul, regardless of whether others can see it or not.

LG: What advice do you most often give your students?

CH: Follow your heart, find your gift and do what gives meaning to your life.

LG: What do you care most about in your work?

CH: That it is genuine, and that I continue to learn from it and share it, that I might inspire others to do the same.

Carol, seeing your incredible energy as manifested in your work is truly inspiring. Thanks. Kc

You didn’t mention me. I believe that I am a large influence on your work. George

Excellent interview

Carol,

I am so glad to come across this excellent interview. Your paintings and drawings inserest me greatly, as they continue to evolve over time, sophisticated, highly skilled drawing and imagery that is also completely personal.

On another matter, I haven’t been in the City in too long but am coming Wednesday-Friday. Possible to meet?

Warmest,

Lorna

so wonderful to read this interview Carol!

happy to read this interview Carol. you are a constant inspiration to me with your imagination, talent and creativity. why does Georgie Porgie have to elbow his way into everything? warm wishes, Maureen

Carol, excellent interview… I found that I agree with you on most things… I have similar feelings behind my work… esp the intuitive part. Thank you for doing this, and for sharing it. Just superb!!!! Jack Dickerson