I am pleased to post this email interview with the NYC based painter Carol Diamond. I have been following her work on Facebook and have been continually struck by the original and dynamic way she paints urban structures with her modernist, abstract sensibility. Some of these works evolve out of observed, on-site engagements others are studio inventions. Taking the urban theme even further, she also makes assemblages and collages from found objects that were discarded onto city streets.

Diamond explains more in her website’s artist statement:

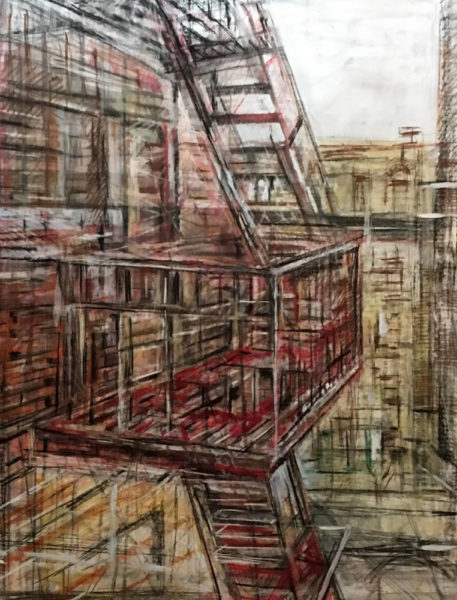

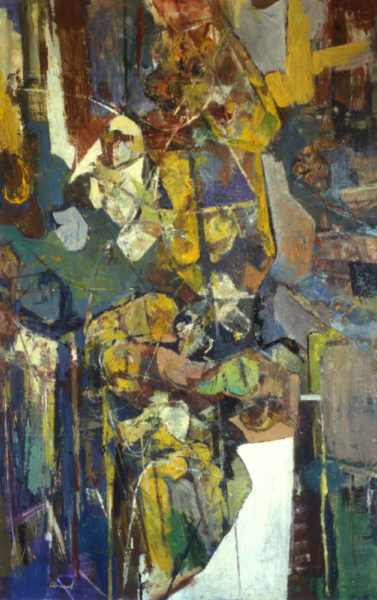

…“I feel a strong parallel between the making of a painting and the building of a wall, or a structure, an edifice. Each involves construction and deconstruction, and provides refuge, a haven. In the case of my interest in religious architecture, there is the element of sanctuary and sacred geometry”. For years Diamond painted directly from street scenes, churches, bridges and boats. Through abstraction she found her way back to city sources, collaging found debris into ready-mixed concrete on wood panels. Diamond divides her compositions with large movements such as arcs, diagonals, and verticals which combine her deep connection to early Modernism, in particular the works of Malevich and Lissitzky with her axial drawing methods related to Renaissance linear Perspective. Anselm Keifer’s work which unabashedly uses linear perspective, has been inspirational since her youth, where emotion and history are transformed into the most rugged images of materiality and depth by any living artist.

Since 2000 Diamond has taught at Pratt Institute where she is an Associate Professor. Diamond studied at the New York Studio School in Manhattan and received a BFA in painting from Cornell University. She has lived in Brooklyn since the late 1980’s and currently lives in Manhattan. She has had solo exhibits in the Gold Wing Gallery and the Alliance Gallery, New York City, as well as many other group and solo shows in New York City, Upstate New York and nationally.

She recently had a solo exhibition of her work at the Kent State University in Canton, Ohio – Threshold: Selected works by Carol Diamond

This show was reviewed in the ARTWACH blog by Tom Wachunas who stated:

“… There are several methodologies or modalities present in this impressive collection of works spanning (I’m guessing) at least several years: Large-scale abstract paintings, mixed media works on paper, relief collages, plein-air drawings of architectural sites, and sculptural assemblages of found debris.

Radiating from most of this formal diversity is an aura of vintage Modernism. It’s a visceral kind of tenor – alternately gritty and refined, delicately ornamental and muscular, literal and symbolic – which binds all these works together into a collective embodiment of a distinctly urban sensibility. These are fascinating explorations of facades, spaces, structures, and metropolitan detritus, comprising something the artist knows intimately – something you could call big city zeitgeist.”

I would like to thank Ms. Diamond for agreeing to this interview and for sharing her thoughts on her art with the readers here.

Larry Groff: What made you decide to become an artist?

Carol Diamond: That’s the easy question. I never decided, I just always did it. Always took an interest in art classes and making things, from doll clothes to papier-mâché animals in my after school art class in the basement of a family friend, Joan Silberbach in the Cleveland suburb where I grew up. We worked with enamel, tin foil relief, a lot of papier-mâché, and I did my first oil painting (I still have it) all in browns, with dried flowers and a skull!

Then High School it became real, going to a progressive prep school with a great arts facility; theatre, pottery, photography, painting, fiber art. So much experience there, inspiration from teachers, amazing creative friends, and freedom. I was pouring paint on unstretched canvas in my parent’s garage, thinking I was Pollock. I did a painting for school “in the style of” Dali, where a cloudy sky turns into a blue curtain entering a window. A rose sits in a glass vase. My sister and I took outside classes at the Cleveland Museum of art.

LG: What was art school was like for you?

CD: I decided to go to Cornell to get a university education and have a Fine Arts Department with no emphasis at all on Commercial Design. The Cornell School of Architecture Art and Planning was that. It was relatively hands off atmosphere but I did bond strongly with a few teachers, one of whom (Gillian Pederson-Krag) vociferously encouraged my 2 closest friends and I to stay away from studying abroad for our junior year (“If you go to Rome you will want to be buying shoes and not be in your studios”) and instead to attend the New York Studio School, where she felt sure we would benefit enormously.

So in 1980, my sister joined us from the U of Michigan and together the 4 of us walked day to day from our 6th floor walkup apartment on West 10th Street across Christopher Street to 8 West 8th Street, wherein began my true education. Though it was not even the tail end of the New York School era, we thought it was. We were in the wake of Pollock and DeKooning, Cedar Bar stories told to us by our great mentor, Nick Carone, the draftsman and voice of the Hans Hofmann School practice, along with European history. We read the Hofmann’s Search for the Real, and Kandinsky, but the daily practice was all about drawing the figure, Giacometti, plastic space, form, both classical and deconstructed.

Nick Carone, Mercedes Matter, Rackstraw Downes, Paul Russotto, Charles Cajori and others showed us passion, pushed us to see; cared enough to be frustrated when we couldn’t see, and celebrated us when we could.

LG: Can you say something about how your work has evolved over the years?

CD: Art follows personal growth and emotions, along with artistic influences. And these artistic influences are affected by what an artist is needing/trying to say, all unbeknownst to the artist. It’s all intuitive. Our interests, psychology, predilections, skills and training all guide and lead us. I feel lucky when I’m able to follow myself into terrains of expression and discovery. But as the perspective changes from the young to the mid career artist: my dreams have subsided and I’m every bit as unknowing about what tomorrow will bring as ever. There is no safety.

Williamsburg Bridge, afternoon, 24×28 inches, o/c, 1997, Collection of the Portland, Oregon Museum of Art

LG: In the 90’s you worked a lot from life making painterly, gestural landscapes, figures and still life what where some of the reasons you changed and how was your transition from working perceptually to more studio-based abstraction?

CD: At the Studio School I learned that Abstraction could come from elements of perceptual painting, such as the abstraction of Picasso and the cubists. Non objective painters used shape without observation of form, and abstract expressionists integrated emotion through gesture into abstract space.

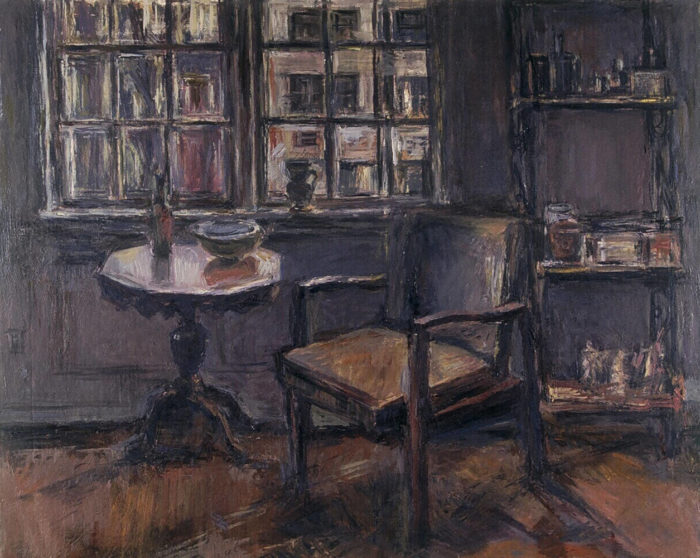

I do have a group of early abstract paintings I did in the late 80’s, but I was always looking at a set-up of some sort, even a chair against the wall. Then the set-ups and objects became more clear and I maintained an aesthetic of perceptual painting a la Giacometti and Cézanne, destined to follow the existential side of modernism related to making a thing exist in space, often by a deconstruction process. I was dedicated to plein air and still life/interior compositions, painting in a tonal palette, and then through that developed my love of cityscape and gritty urban areas albeit with a somewhat romantic glaze. This culminated in a series of works done in Williamsburg, painting the East River bridges, the Domino Sugar Factory and ships in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Something happened though after showing these works, where I felt too comfortable with my process, I had “gotten it”. I was afraid to become a traditional landscape painter going from scene to scene.

I segued to studio paintings with a trip to Southwest England painting and drawing the rocky coast and in Brittany, France, finding a more organic overall approach to line and shape. The abstract paintings I began on my studio floor involved poured curvilinear movements, and scratching through layers of paint as a way of drawing, finding content. The space was compressed, cubist inspired, while also favoring early Northern Renaissance sense of flatness and rich color.

My still life and landscape work had mainly used short vertical and horizontal strokes, the plus/minus Giacometti structure. Here I was now using mainly Circles and Arabesque motions.

I got pregnant soon after and began raising my baby! My husband died two years later to illness, then my mother in the same year.

My paintings became more spare, with a strictly black and white palette. Then broken glass found from the street and other debris entered the palette and I have since been experimenting with relief elements and collage materials in my work. I had worked as an Antiquities restorer in the late 90’s, and was lucky enough to have helped repair broken Greek Attic vases, Chinese Bronze objects and much more. This relation to materials from Antiquity had a strong but indirect influence on this direction in my work. For some years now I’ve also returned to architectural drawing to continue with my interest in concepts of Structure and the building/deconstructing process.

So the genres of representation and abstraction are fluid, and keep following conceptual needs in my understanding/expression of form and space and SELF IN THE UNIVERSE!

LG: I just read your brilliant recent (7/27/18) essay Carol Diamond on Al Held on the Painter’s on Painting site.

With this in mind I’m curious to find out more about some how you juxtapose flatness and deep space in some of your current works, like in your Fences or Abonica. I am seeing some connections to Al Held’s use of perspective in his black and white paintings and his later works with abstracted geometric forms in space. Of course there hugely obvious differences but it struck me that many of the collaged shapes have these dramatic linear perspectives that are cut and positioned in such a way to induce a dizzying array of spacial movements not unlike some of the compositions he was involved with. I always loved how he thumbed his nose at the rules about not violating the integrity of the picture plane or modeling form as a big no-no.

Anything more you can say about this?

CD: Well you basically said it! And I’m very glad you can see this connection. As you said, Held “thumbed his nose at the rules about picture plane integrity or modeled form” and this is how I see him and I feel this gives license to my work to play with these rules as well. While I am impressed and enamored by many painters who develop juicy painterly flat chunks of color on the picture plane, I do crave form, love geometry, and space. I’ve grown into the love of perspective because of my teaching perspective and drawing systems, and have integrated diagonal orthogonal lines and vanishing points into my city drawings. I felt guilty about this until I saw Held’s late work some years ago and these works inspired me to search for my own synthesis between the picture plane and deep space. Why not?

I’ve missed the space I developed in my plein air paintings and current drawings in my abstract work; missed the sense of space and atmosphere. The collage pieces from photos of sidewalks, railings, angles, textures, fused with my extended passages directing the eye and tilting the plane – this has the beginning of synthesizing my two parallel bodies of work. The many possibilities of this current direction in my work excites me a great deal.

LG: Please tell us something about the ideas and process behind your assemblages and collages. I’m particularly curious about how you collage elements like digital photos and other physical objects – flattened cans and the like.

CD: I’ve been picking up broken glass for a long time. (at first I embedded everything into Latex paint) I have been using flattened cans more recently and other debris and other three dimensional found pieces I can assemble. I also save and use plastic to-go containers as plaster molds to create sort of mosaic plaques. The debris aesthetic is peculiarly connected to things and their destruction, their remains; the instant a bottle is crashed to the ground, the rusting of mechanical parts, scrap metal, colored cans. I love cement. The photo elements evolved to be able to work on paper and develop spatial drawing through shadows and ornamentation, literal elements photographed then distorted from context. Like the metal elements, coke cans and such are out of their natural element, as was practiced in Dada and assemblage art.

There can be a transformation of ANY material into art – paint itself is transformed. Why not found materials? Our materials have two lives; their original purpose (bottle to drink from, paint to make colored surfaces from) and the metaphor, the content.

I have also been influenced by Celtic Art, medieval stone carvings, mosaic inlaid objects and stained glass windows. And of course architectural forms, mainly arches and domes.

LG: Many first generation abstract artists believed in the potential of painting to reveal meanings of a metaphysical, symbolic nature and that abstract art has the potential express great human tragedy and perhaps hope. Do you think art can or should address the troubles of our times, like Trump, climate change and the like?

CD: I like this subject because we are now faced with a climate of intense political upheaval, the troubles of our times as you say; many artists have shown their activism, taking on great causes while hoping to express their own voice in art. The first part of your question talks about Metaphysical and symbolic qualities in art which refer to more universal attributes such as hope and tragedy rather than an election or even political upheaval. I do think Art is about humanity, and being human. I just don’t think of artists as being activists (except perhaps as a separate duty from making art) beholden to do anything but develop their story, their craft, their commitment to emotional openness and truth and hard work.

We live and create from our own moment in time, it’s always been this way. We are not separate from the world around us, so anything that enters us can enter our work.

LG: Would you say you try to bring a spiritual dimension to your work? Would that mainly be something to drive your work on a personal level or is are you trying to communicate these concerns to viewers?

CD: Well yes there IS a spiritual dimension to my work but I don’t try to make this happen. For one it comes from the aspect of art history I connect to that is religious. Early Christian paintings and sculpture especially, tell the stories that have impact to being human and showing humanity. The deposition scenes showing Christ falling into the arms of Mary, to me show the weight of death in our arms, the weight of carrying the burden of love and loss in our life. But as you say, this intensity might be more of the spiritual in art that “drives my work on a personal level” more that anything I try to communicate in my art.

I express spirituality in my love of the Arch form, the protective symbol, threshold to another dimension. The Dome, I’ve drawn and painted, which means much more than I understand or can express, but it’s certainly related to bigger subjects. And I completely believe in Art as a meditative, life affirming activity; to make, to behold or experience. Art is connection to life, history, and to the present.

LG: Are existential questions–like our place in the universe or what it means to be alive–too big for paint? Why not just make art for art’s sake alone?

CD: Not too big for paint, no. From Kandinsky to Chardin, artists paint about what it is to be alive, what it is to notice something, have something to say, experience emotion and love form and poetry. But art can’t be didactic; probably asks more questions than it answers.

Leave a Reply