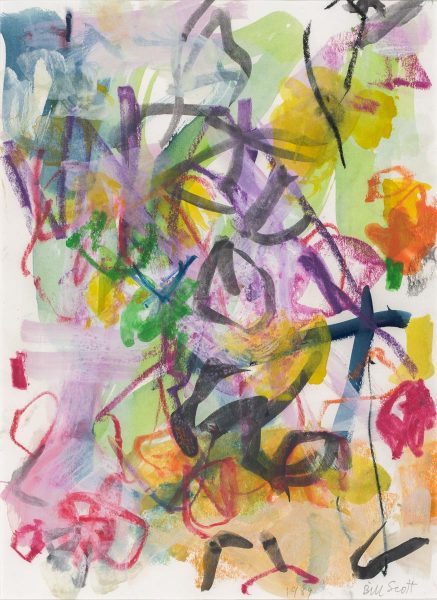

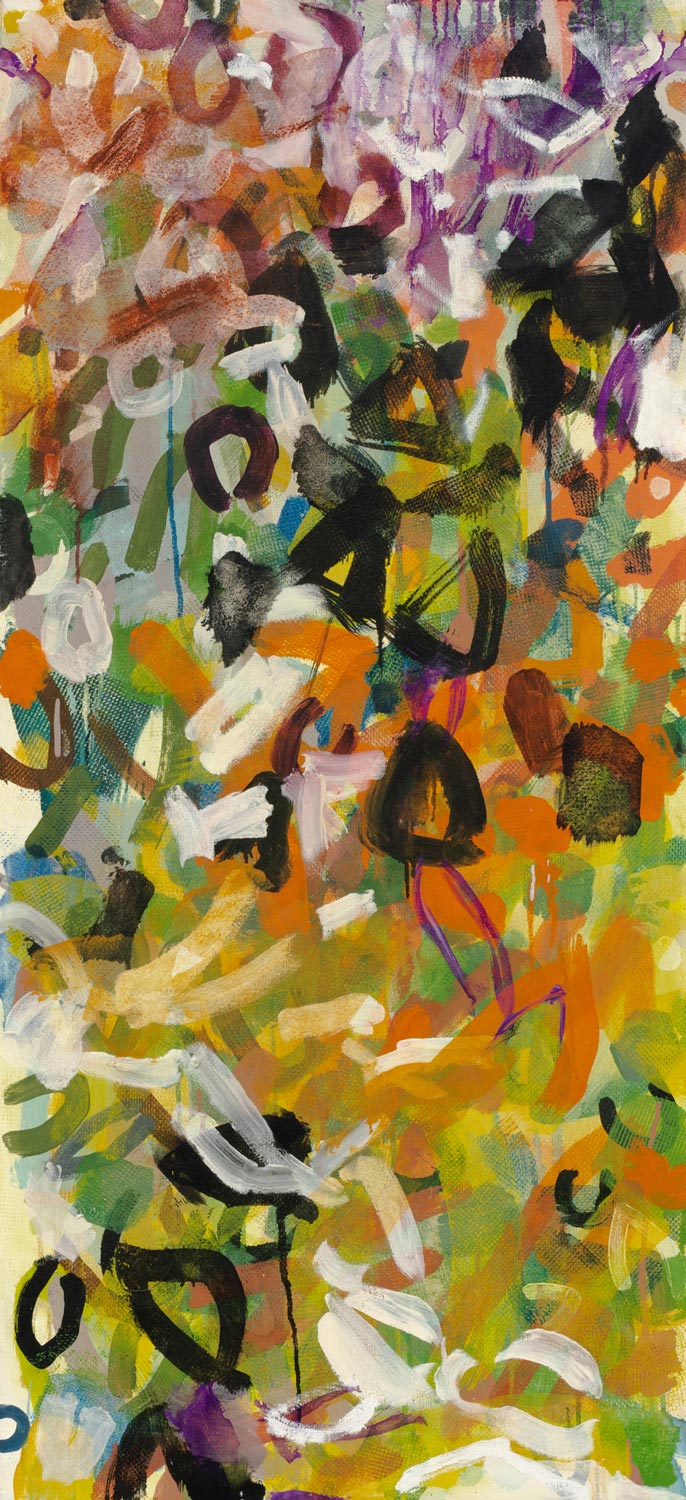

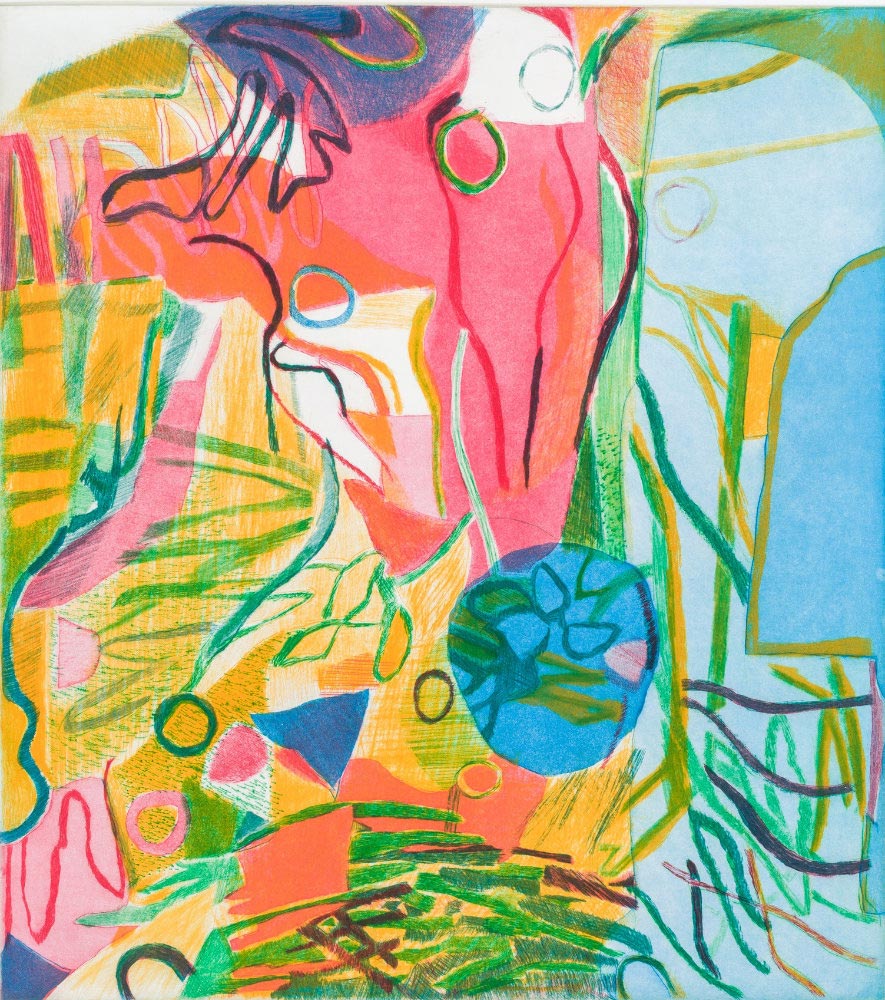

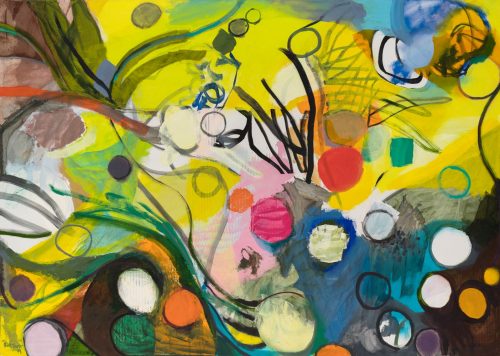

I’m delighted to share this email interview with Bill Scott who writes from his home in Philadelphia. I’ve long been intrigued by Bill Scott’s paintings and prints and was lucky to view an exhibition of his works last year at The Pierre Hotel in NYC. He was scheduled to have a solo show this April at his gallery, Hollis Taggart in Chelsea, NYC, NY. that was postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. His unapologetic celebrations of beauty, lyrical and joyful abstractions acts as a salve of color and light and a reminder there is still life and hope in our feverous times.

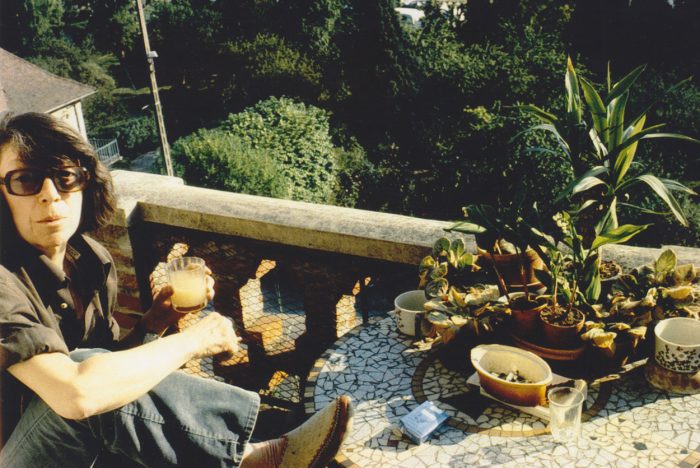

Scott’s 2016 interview by Jennifer Samet on hyperallergic.com’s beer with a painter is a fabulous in-depth look at his background and process. Ms. Samet asked him about the associations and motifs present in his work, Scott replied by saying; …

“…I think I paint bittersweet fictions. I don’t believe the imagery I paint exists. I am not so removed from the world that I think it is pleasant out there. I think it is close to awful. We are walking towards extinction. So, why wouldn’t I paint the Garden of Eden or something pleasurable? What am I going to gain, spiritually or emotionally, from painting something miserable? I would much rather live in a fantasy world. I want a kindness in the painting. I want there to be an emotional ease. Generally, I don’t feel that in life, so I want it to exist in the paintings.”

Bio from Hollis Taggart

Bill Scott began his career studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 1974 to 1979 but considers longer periods of working informally with painters Jane Piper and Joan Mitchell as the pivotal influences of his own painting.

Scott has exhibited widely over the past three decades at museums that include Swarthmore College, Hollins University, the State Museum of Pennsylvania, the National Academy Museum, and the University of Delaware. Major public collections with Scott’s work include Cleveland Museum of Art, Delaware Art Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute Museum of Art, and Woodmere Art Museum. His work has been reviewed in Art in America, ARTnews, The New York Times, and the Philadelphia Inquirer. In 2006, he was awarded a Distinguished Alumni award from the Pennsylvania Academy.

Scott was raised in Haverford in suburban Philadelphia and studied painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 1974 to 1979. Throughout this time he also studied informally with the painter Jane Piper (1916-1991) whose studio he visited frequently.

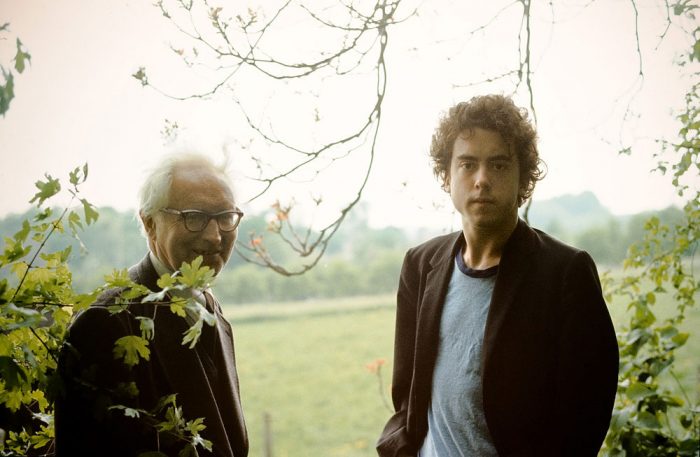

In 1980, while living in Paris on a travel prize, he met the American abstract expressionist painter Joan Mitchell (1925-1992). In subsequent years he stayed at her home in Vétheuil and painted in her studio. After Mitchell died, he wrote an appreciation of her published in Art in America.

Beginning in 2004 Scott has been represented by Hollis Taggart Galleries where he has had seven solo exhibitions.

In a 2007 review Mario Naves wrote in The Observer.com

Bill Scott is a radical artist, but not in the sense to which we’ve become accustomed.

Mr. Scott, whose abstract paintings and prints are on display at Hollis Taggart Galleries, doesn’t rely on slick theatrics, obtuse theorizing or technological appropriation. He has the temerity to plumb something deeper than his navel or the superficialities of pop culture. In an era dominated by secondhand conceptualism, he wrestles with firsthand experience. The confrontational act that Mr. Scott engages in? He looks out the window and likes what he sees.

Looking Through is, in fact, the title of Mr. Scott’s exhibition, calling forth questions of viewpoint, transparency, distance, detachment and, in the end, joyous connection with the world. The paintings demonstrate that what’s out there is worthy of our time, attention and, in this artist’s hands, unalloyed pleasure.”

all photographs of Bill Scott’s artwork are by Joseph Painter.

The artist wishes to thank Gretchen Dykstra for her help in editing this interview

Larry Groff: I don’t know of many painters who are also considered scholars on a certain artist, as you are on Berthe Morisot. You became deeply involved with her work and wrote about Morisot on your own, not as part of an academic venture, is that right?

Bill Scott: When I was young, I painted and drew pictures, wrote short stories, and went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA). I was an insecure and anxious kid, and had no plans for my future. I would never have called myself an aspiring artist or writer. Although people sometimes asked, I didn’t think of where I wanted to be in five years or even in one year. The way my life still continues to unfold feels open-ended and circuitous; it’s not so different from how I make my paintings.

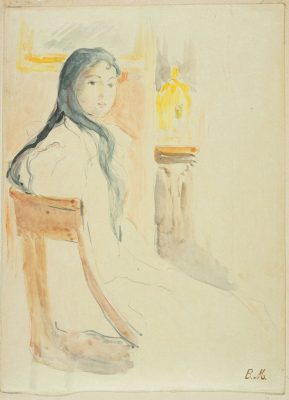

My father admired the landscapes of Canaletto, Pissarro, and Sisley, but appreciated them mostly as depictions of nice-looking places in pleasant weather. He loved the finished images, but had no curiosity about how one made a painting. My mother and grandparents preferred the performing arts, and had little interest in the visual. My fifth-grade teacher taught the class about the lives of artists. I still remember seeing the big 1966 Édouard Manet exhibition at PMA. My parents both saw how learning about painters and painting would be valuable for me. So, for my twelfth birthday, my father gave me a small book on the Impressionists; it included one reproduction of a painting by Berthe Morisot.

I had been looking at monographs on other painters and those books allowed me to see the stylistic continuities and changes that occurred in their work. Compared to the others, Morisot was a mystery. Aside from a very good English-language volume of her letters, there was little documentation available. I could find only three or four postcards of her paintings. If her work was included in books on Impressionism, there was usually only one example shown. The National Gallery of Art (NGA) had several early, one mid-career, and one late painting on display. I also saw a late painting at the Phillips Collection and another at the PMA. I was baffled by the stylistic shift between her early and late works. At that point in my life, not unlike many people I have since met, I didn’t see beyond a painting’s subject. Slowly, I became less interested in the subject and increasingly intrigued by Morisot’s energetic paint application and sketch-like aesthetic. Reproductions failed to convey these aspects of her work, and I learned far more by seeing the paintings in person. It was only after I had painted for several years that I began to better understand the complexity of her use of color, composition, drawing, and paint application.

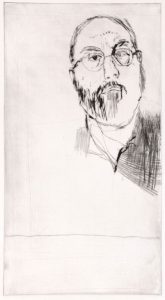

Within a few years, I began writing letters to museums and individuals to ask if they owned any works by Morisot. Many people responded and often sent photographs. Eventually I met two of her grandsons, who showed me works they had recently inherited from their mother. They also took me to see places where Morisot had painted. About a decade after diving into all this—I was now in my mid-twenties—I met Charlie Stuckey. He reached out because he’d been hired to organize a traveling exhibition of Morisot’s work that would open in 1987 at the NGA. I was co-curator and, of course, I wanted to include everything she’d ever painted. Charlie introduced me to his friend Juliet Wilson-Bareau, an English scholar and a specialist on Goya and Manet. At that time she was also working on Vuillard. I credit both of them with pushing me to look at Morisot with a more discerning and critical eye. Charlie and I traveled together off and on over four years to see many of her paintings. After the exhibition was finally installed, we walked around the galleries, just taking it all in. It was as if Charlie had read my mind when at one point he turned to me, smiled, and said, “Don’t you wish we had it all to do over again?”

Entrance to the exhibition, Berthe Morisot: Impressionist, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1987. Photograph

LG: Did you study art history or writing in addition to studying to become a painter?

Bill Scott: I never formally studied art history or writing. When I was in high school, someone told me American Artist magazine was going to publish an article on Morisot. I didn’t look much at art magazines. This one was sold in art supply stores and, for the next few months, whenever I saw it, I’d look to see if the article was there. Eventually, never having found it, I wrote the magazine’s editor to ask if I had somehow missed it. She replied and surprisingly invited me to write it. I did it because the editor agreed to include a color reproduction of a painting I loved but had never seen reproduced in color. The article was published in the fall of 1977, when I was in art school. At first, I didn’t say anything about it to anyone. But one of my classmates saw it and asked, “Hey, that painter you like so much—her name is Berthe Morisot, right?” When I replied, “Yes,” she showed me her copy of the magazine and proclaimed, “This is unbelievable! Did you see this yet? Someone with your exact same name wrote about that very artist you like so much. Isn’t that weird? What are the chances?” I felt crushed, but mumbled something like, “Oh, really? Who would’ve thunk it?”

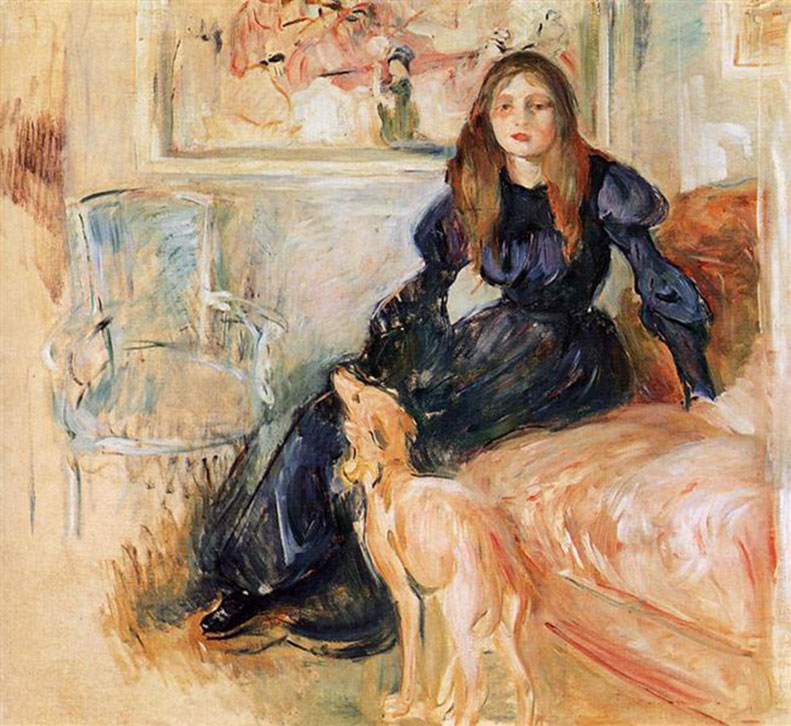

Berthe Morisot, Julie Manet with her greyhound Laertes, 1893, Oil on canvas, 28-3/4 x 31-1/2 inches Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris

I loved Fairfield Porter’s paintings and saw his exhibitions. Before I knew his paintings, however, I had read his 1960 review of a Morisot show and had a copy of the book he wrote on Thomas Eakins. I veered toward accounts of painting written by artists or their close friends. I read reviews and articles by Elaine de Kooning and the books by Hans Hofmann and Charles Hawthorne. An older painter gave me books on Renoir written by his son and another by his only student, the painter Jeanne Baudot. After the Morisot article was published, I started writing about living artists. They were all significantly older and I learned from how they reflected on their own lives and artwork. I wasn’t blown away by all of them as artists, but the interaction gave me the opportunity to meet and talk with many I probably wouldn’t have known otherwise. Eileen Goodman and Edith Neff, both of whom were realist painters, were wonderfully encouraging. They proofread some of my articles and even suggested titles when I couldn’t think of one. I suspect I’d cringe now were I to read them again. I doubt they’re as good as I felt they were then, but in meeting and interviewing so many artists, I learned much more than how they painted and their preferred materials. I learned how they felt about their lives, friendships, beliefs, hopes, and disappointments. I was naïve, but grateful I met artists who allowed me to see the art world as a cooperative and caring community.

Arthur B. Carles: Abstract Bouquet (1939) Oil on canvas, 33-1/2 x 39-1/2 inches, Woodmere Art Museum

LG: Arthur B. Carles, a leading early figure in modern painting and a faculty member at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), once threw model casts down an elevator shaft, presumably as a statement against academicism at PAFA. Many art schools today have reduced or eliminated traditional figurative training, such as drawing from casts or learning anatomy. How necessary is teaching representational skills today, especially for students who want to paint more abstractly or conceptually?

Bill Scott: I’ve been asked that question before—it’s a difficult one for me to answer. I’m apt to romanticize my own education because those memories transport me back to how I felt when I was young. It’s easy to wonder why other people wouldn’t want to do that too.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Study for the mural The Golden Age, 1843-1848 Graphite on wove paper, 10 7/8 x 8 3/4 inches Philadelphia Museum of Art

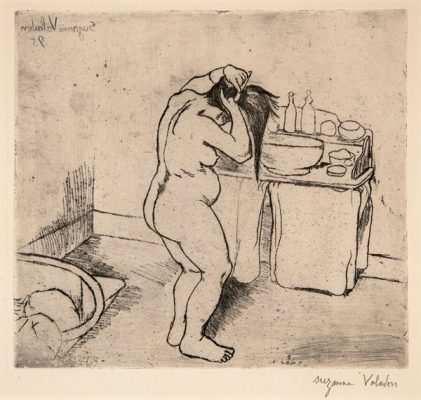

Suzanne Valadon, Catherine Nude Arranging Her Hair, 1895 Soft ground etching, 8 ½ x 9 ¼ inches, Collection of Bill Scott

There’s a beautiful figure drawing by Ingres that I looked at each time I visited the PMA. I filled several sketchbooks with pencil sketches I copied from it, along with others reproduced in a book of his figure drawings. I also made a bunch of pencil copies of figure drawings and etchings by Suzanne Valadon. In the first year of art school, I attended the required cast drawing, figure drawing, anatomy, perspective, and portrait painting classes. It was work and I didn’t want to do a lot of it. Some of the teachers had preposterous personalities, but learned I didn’t need to like people to learn from them. My impression is that education has since become an almost exclusively feel-good experience. I certainly didn’t want to do all of what I was told to do in school, but at what point in our lives are we able to do only what we want? When I was in school, I was just so grateful the draft had ended. I’d always been certain I’d be drafted and killed in Vietnam. Hence, to be in art school was a gift.

Once my good friend Evan Fugazzi, a wonderful younger painter who then painted representational imagery, asked if I could talk with him about how one paints an abstraction. I offered to meet for coffee, but warned him I had no answer for him. I was grateful for his inquiry because he really made me think and question myself. Later that evening I described the meeting to my friend Kevin Finklea, a minimalist painter and sculptor. His response amazed me, because in one sentence he said everything I had hoped to say. “Hasn’t he realized,” Kevin said, “that there’s nothing abstract about not painting representationally.”

LG: I understand you once helped put together a show of Carles’s work. Has he been an important influence for you?

Bill Scott: Even before I was an art student I met many older artists who had studied with Carles. He was their hero, but they were mine. But I learned about him from them. He began his career as a very good academic painter and he later lived in Paris, where he met Matisse and embraced Fauvist color. By the 1930s, he made abstractions that foreshadowed Abstract Expressionism. In 1941, at age fifty-nine, a stroke forced him to stop painting. He died a decade later, before I was born. Barbara Wolanin, a curator based in Washington, DC and the foremost Carles expert, organized a large traveling exhibition in 1982 to mark the centennial of his birth. That was the first time I saw so many of his paintings in one place. I admire how his vision continued to evolve.

I first learned about Carles’s student Betty W. Hubbard because someone told me she had known Berthe Morisot’s daughter. She translated Morisot’s correspondence and paid for its English-language publication. When I was in high school, I met Hubbard’s eldest daughter, Leslie Symington, and helped to photograph and catalog all her mother’s paintings, watercolors, and pastels. Soon thereafter I met Morris Blackburn, Quita Brodhead, Moy Glidden, Faye Swengel Badura, Elizabeth Godshalk Burger, and other artists who studied with him. I was closest with Jane Piper, who was one of his very last students. Without doubt Carles was an incredible teacher and a magnetic personality. Even years later, all his students spoke of him as if he were still some sort of aphrodisiac. He was a continuing inspiration on their lives and art.

In his classes most students painted like him. Decades later this caused confusion when those paintings, unsigned, would appear for sale in auctions or commercial galleries. The Carles-like color would prompt hopeful sellers to identify these as original works by Carles. Once you saw how the individual students painted it became more obvious who in his circle painted which ones. Hoping to correct this, in 1988, I organized an exhibition of work by his students at PAFA. Then in 2000 I organized a more comprehensive student show for Woodmere Art Museum, and presented it in conjunction with the Carles exhibition organized by Hollis Taggart and Barbara Wolanin, when it traveled there. All these projects were huge learning experiences. I think in doing all this I unwittingly shot myself in the foot because ever since I’m cited as a painter working in the Carles tradition. It may be true, but I’ve never liked feeling as if I am being put in a box.

LG: You mentioned that you were close to Jane Piper—what are some important things you learned from her?

Bill Scott: I loved Jane. I met her in late 1972, after seeing a show of her paintings at a commercial gallery in Philadelphia. I wrote her a letter and she responded with an invitation to meet and see her studio. Thereafter, I visited her every week or so and saw how she changed her canvases as she worked on them. She always asked me what I would do to the painting she had on her easel. She was very patient with me and spoke with me about my paintings. Although she taught, I felt she was wary of art schools that awarded lots of prizes and instilled students with a false sense of accomplishment. She spoke of art and artists as a community that existed internationally. It was refreshing for me because I encountered many artists who felt nothing mattered beyond the few square miles of Philadelphia bordered by Vine and South Streets and the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. After Jane died, I met a few of her former students who disliked her and felt her teaching was formulaic. I remember feeling crushed when I heard that, but realize I feel that same way about some of my own former teachers, who I know were loved by my friends. I never attended one of Jane’s classes and our relationship was one on one. After the first Morisot article was finished, I wrote an article on Jane and helped her catalog and photograph all her early canvases. She told me, at the suggestion of Carles, she attended Hans Hofmann’s Provincetown school in the summer of 1941. In hindsight she said, “I could have learned much more from Hofmann than I did, but I thought Carles had said it all in simpler terms.” That’s the way I felt about Jane in comparison to the other teachers I studied with.

After art school, I worked five years in the gallery where she showed her work. I didn’t always like the job, but I always enjoyed organizing her exhibitions with her. She had shown her paintings in New York when she was young and when she was dying she wanted very much to have another exhibition there. One evening I called to talk with her good friend Charles Cajori, a painter who had taught with Jane at the New York Studio School, to ask if the show at the school might be possible. He went out of his way to arrange an exhibition of her last works that Jane and I organized. One of the founders of the school was Mercedes Matter, Carles’s eldest daughter. Since Carles had been Jane’s mentor, she and Mercedes had known each other their entire lives. They cared about each other, but there was a strange rivalry between them and Mercedes had undermined Jane a few times. Rumors had circulated for years that Carles had affairs with many of his female students, and apparently Mercedes always wondered about him and Jane. She finally asked Jane point blank if she had slept with Carles. Jane replied, “No.” When Jane told me this story, she laughed and said, “And then Mercedes asked me why on earth I hadn’t slept with him! She was impossible. It was as if she were mad at me. There was no pleasing her.”

The exhibition opened in January 1991 and looked beautiful. When Mercedes arrived midway through the opening reception, she led Jane out of the gallery and didn’t return for about forty minutes. When I later asked Jane what had happened, she told me Mercedes had taken her to see one of her own paintings that she’d had someone hang for her in an adjacent room. I couldn’t believe Jane was expected to talk about and praise another painter’s artwork in the middle of a reception when her own friends had come to support and encourage her. Jane was better than I at tolerating narcissists.

One week after Jane’s opening, my own mother died. I’d been trying so hard to somehow keep both Jane and my mother alive. My father had died the previous year and I was paralyzed by sadness when my mother suddenly died. I was still in shock when Jane passed away several months later. I felt as if the core of my world had disappeared. I’m forever grateful for my friendship with Jane. Her voice is no longer there, but for a number of years, hers was the one I continued to hear most clearly whenever I was alone in my studio.

LG: You also studied informally with Joan Mitchell in Vétheuil, France. Having an influential painter like her as a mentor must have been challenging at times. What was it like to study with her? Was she more beneficial or problematic in terms of finding your way as a painter?

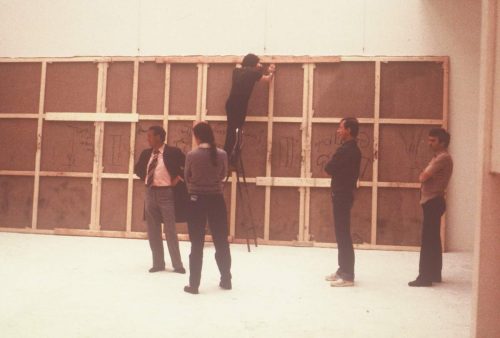

Bill Scott: I saw Joan’s work in her 1974 solo exhibition at the Whitney, but it wasn’t until I saw her paintings at the Galerie Jean Fournier in Paris in 1980 that I fell in love with them. I first met her when she was installing there. She was engaging. She handed me a bottle of beer and immediately enlisted me to help hang her 9 x 23 1/2 foot, four-panel canvas, The Goodbye Door. A week later at her place in Vétheuil, northwest of Paris, I celebrated my twenty-fourth birthday with her. Joan invited me to come back and stay the following summer. She said I could help feed her four dogs and promised that the kid down the street would teach me to speak French. Most importantly, she said, I would have uninterrupted time to paint. Joan lived in a large house next to one where Claude Monet lived a hundred years earlier. The landscape appeared pretty much the same way I imagined it had been when Monet was there; it was truly like standing inside one of his paintings. The Monet landscape, however, proved to be the most seductive backdrop to what became a traumatic summer. When I told an older French woman that I was staying with Joan, she snapped back, “Don’t tell me anything about Joan Mitchell,” she warned. “She’s destroyed more lives than any one person has the right to do.”

It was astute advice. At times Joan was very kind, but she could also be cruel in a way unlike anyone I’d ever met. Before meeting her I painted still lifes and figures. In Vétheuil, I stayed outside and tried to paint landscapes, but quickly veered toward abstractions that included elements of trees, plants, and water. Another painter who was staying there, Joyce Pensato, remained inside painting self-portraits. Whenever it rained or was too cold, Joyce let me paint with her in the underground room that served as her studio. Joan referred to our studio as the cistern. She had installed painting racks along one wall where many of her earlier large unsold canvases were stacked. We had a key to the door. When she gave each of us a key to our studio, she cautioned us to always be careful who we allowed in to see our paintings. Joan occasionally would ask to see what we were working on, but usually she waited to be invited.

I painted every day and at lunchtime walked around the village or down by the Seine. After we had dinner together, Joan usually walked the dogs up to her studio where she painted until 4:00 or 5:00 in the morning. If a painting was going badly or if she was waiting for the paint to dry, she’d postpone going to her studio. On those evenings we’d all watch TV together while Joan drank a huge bottle of Jack Daniel’s. She had a dual personality that was exacerbated when she drank. When she was filled with love and wonderment for painting she called herself Little Joan. I loved Little Joan. But without much warning Little Joan inevitably became Big Joan, a cruel and terrifying person. Once Big Joan was furious because she had given Joyce several very good tubes of earth colors. She complained Joyce had wasted the paint, claiming she might just as well have painted with mud. Later, but too late, Joan realized she had been too harsh. The next morning, she presented Joyce with a small, still-wet, vertical painting she made after we’d gone to bed. Joan purposely painted it with earth colors, mostly browns and blacks, intending that it might inspire Joyce to use earth colors a little differently. She handed the painting to Joyce. It was a gift.

Joyce and I didn’t stay in touch after I left Vétheuil. But about six years later, we ran into each other in New York. Typical for me, I immediately started to apologize for having been so crazy when we shared that studio. She stopped me. “There’s no reason to apologize,” she said. “You were the only sane one there, because you left. You knew to leave. I’ll always remember the morning you left,” she added, “when you gave me the phone number for the taxi service and tried to teach me the French words to order a cab and get myself out of there.” A moment later her eyes lit up as if she was visualizing something. She proclaimed, “Hey! Remember that little painting Joan gave me? Well, I left it there just to spite her.”

I thought Joan was one of the greatest living painters. I realize this was a burden for her to know and it took me a few years to learn to never tell her how much I liked her paintings. Admirably, Joan was egalitarian and generous in her curiosity about other artists and their work, but her scary side negated her ability to be as helpful as she wanted to be. One evening, after a dinner with four younger painters, Joan suggested each of us show our paintings to each other. The next evening she was sad and angry at all of us because, after looking at our work, none of us asked if we could go to her studio to see what she was working on. That was what we had all wanted to do, but we were too timid to ask. Unfortunately, Joan ended up feeling left out.

One summer afternoon a group of New York Studio School students came to meet Joan. While they followed her into the studio one student, Nancy Prusinowski, stayed behind. While everyone was looking at Joan’s paintings, Nancy set up her easel on the terrace and painted a small alla prima landscape of the Seine. Joan must have loved that Nancy preferred to paint and bought her painting on the spot. Thereafter it always hung in her house. Mary Page Evans, a painter from Wilmington, Delaware, was someone Joan liked a lot. When I started visiting again in the late 1980s, a small landscape drawing by Mary Page was always hanging on a wall in Joan’s bedroom. There were small paintings of trees that her friend Carl Plansky painted during his visits. Malcolm Morley visited in the late 1980s and made pencil drawings there. Joan later taped a bunch of them all over the dining room door. An early mostly green painting by Sam Francis was something he traded with Joan for one of her works. I was surprised when a friend of the painter Alex Katz visited. Joan asked him to ask Katz if he would trade one of her own pictures for an impression of a lithograph he made of his dog, Sunny.

The best artworks were in her library upstairs, where we watched TV after dinner. Her small five-panel Little Trip from 1969 hung above the door. The other pictures there included an ink drawing by Franz Kline, a 1950s mixed-media drawing by de Kooning from his Woman series, and an early black-and-white nude drawing by Matisse. There were two early American portraits, a wife and husband, depicting two of Joan’s ancestors. Two or three small bronze figures by Daumier were on a shelf above the television. Seeing them so frequently made me rethink de Kooning’s bronze sculptures, which I’d never much cared for before then.

Joan lived for a long time with the painter Jean-Paul Riopelle. They had separated not long before I first visited. His paintings and bronze sculptures were still in almost every room of the house. Joan talked that summer about her desire to make sculpture, specifically bas-reliefs in clay. She stopped herself from working with clay, because sculpture had been Riopelle’s thing. Were she to make sculpture, she said, she felt she would be perceived as being “under him.” She paused for a moment after saying that because it was important to her to make sure we both caught her sexual innuendo, which was impossible to have missed. On the wall behind the television was a case holding old rifles that she clearly knew how to use. One night, she furiously announced if Riopelle ever tried to return she would take one of the rifles and shoot him dead. Another late night, when she was rip-roaring drunk, she commanded me to take down all of Riopelle’s paintings. She wanted him gone. But I was stunned afterward when very sadly she confessed how, deep down, she believed Riopelle to be a far superior artist to herself and she would miss having his paintings around.

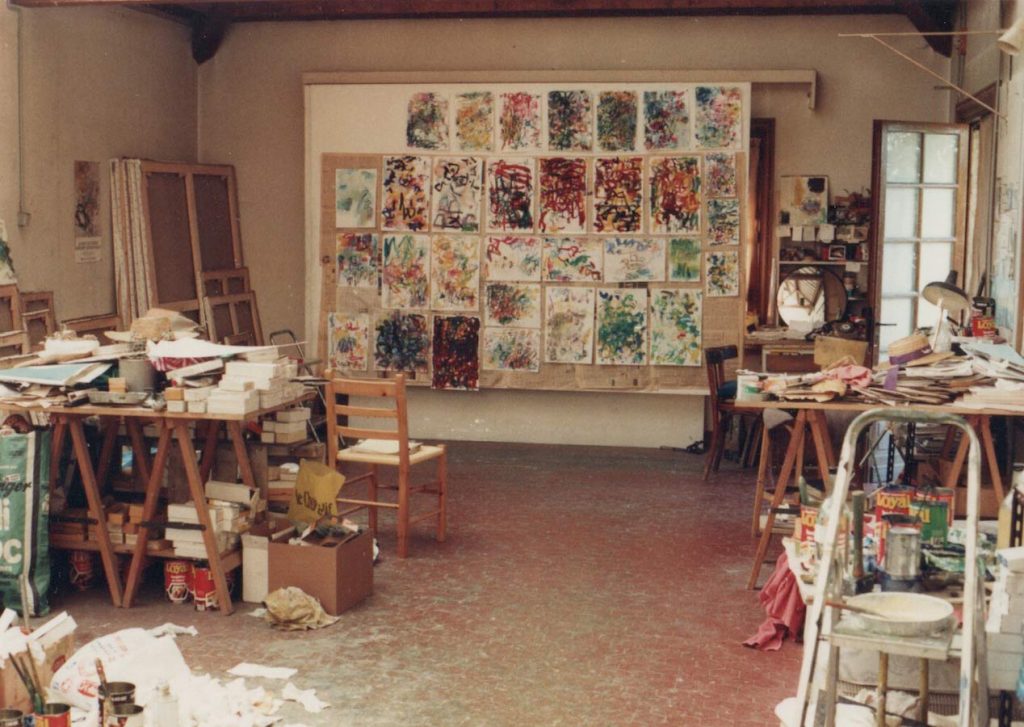

Bill Scott’s watercolors and gouaches hanging on the east wall of Joan Mitchell’s studio, Vétheuil, France,1989

In the fall of 1989 Joan sent me money for airfare and invited me to come stay with her again in Vétheuil. By then she was ill. She promised not to fight with me and said she wanted to give me a painting. Upon arrival she handed me a key to her studio and encouraged me to paint there. I worked there until 4:00 in the afternoon when she would come in to paint. I loved being able to see her paintings and observe how she changed them everyday over the course of a few weeks. She spoke with me a lot about my own work and hung my pictures on the east wall of her studio. It was a wonderful few weeks.

LG: What lesson or memory from your student days resonates most deeply with you today?

Bill Scott: I was so naïve and gullible. In high school I desperately wanted to leave home to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Good friends of mine lived there and I loved visiting the museum there. My friends teased me the school’s students were all taught to make paintbrushes using their own pubic hair—and those would be the brushes I was required to use. I was afraid my friends might not be teasing me. To be safe, I decided not to go. I was such an idiot. It reminds me of what our anatomy instructor, Robert Beverly Hale, once told us: “We see what we already know, until we eventually know what it is we are seeing.”

I also remember on the first day of art school when the dean, Henry Hotz, gathered all the incoming students for a meeting. He forewarned us of difficulties we were likely to encounter in our pursuit of being visual artists. The thing I best remember was his prediction: “In five years from now, only ten of you will still be making art. And in ten years, only five of you will still be making art.”

LG: Are there any artist biographies that you found particularly influential?

Bill Scott: I still like Philippe Huisman’s 1962 biography of Berthe Morisot and the book on Philip Guston written by his daughter. Other books I go back to include Chatting with Matisse: The Lost 1941 Interview by Pierre Courthion (Getty Research Institute, 2013); My Love Affair with Modern Art: Behind the Scenes with a Legendary Curator, a 2006 book of the collected essays by Katharine Kuh edited by Avis Berman; and Siri Hustvedt’s Mysteries of the Rectangle: Essays on Painting, which I absolutely love and recommend to everyone. I recently read Robin Lippincott’s Blue Territory, which is appropriately subtitled, A Meditation on the Life and Art of Joan Mitchell. I’m about to begin reading the new biography of Nell Blaine written by Cathy Curtis.

LG: You showed at the Prince Street Gallery for a few years before going to Hollis Taggart in 2004. Other than making exceptionally beautiful and masterful paintings, what else did you do that was helpful to you in getting into that gallery?

Bill Scott: I met the folks at Hollis Taggart in 1997, shortly after they presented the exhibition The Color of Modernism: The American Fauves. A painting by Carles was reproduced on the catalog cover. To follow up on the success of that show, the gallery started thinking of how to organize a Carles exhibition. Barbara Wolanin was already involved and I offered to help. Their Carles show opened in 2000. At that point the gallery committed to present a retrospective exhibition for Quita Brodhead to coincide with her one hundredth birthday the following year. Of Carles’s surviving students, Quita was the one who had been closest with him for the longest period of time. The gallery mostly represented the estates of artists and the few living painters they represented, like Quita, were much older. So, it never crossed my mind to try to interest them in my work. Believing there was no chance they would ever show my work, oddly, made our relationship much easier and more relaxed for me. At that time, I was exhibiting my work in a few commercial galleries, but a couple of years later all of them closed. I didn’t know what to do. I told Hollis about the closings and he invited me to have a solo exhibition the following May. I knew him and his colleagues seven years before they represented me. It helped that we knew each other well and had already had our differences of opinion and tug-of-wars that are more awkward in a more conventional artist-dealer relationship. A few years earlier, Hollis once told me he liked my work and lamented that the gallery, back then, did not represent living artists. I teased and shared my hope that my work was strong enough that I would be a dead artist for far more years than I was a living one.

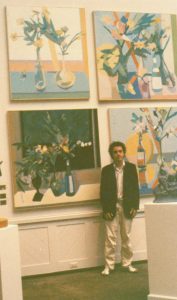

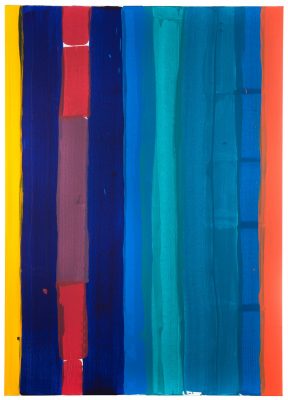

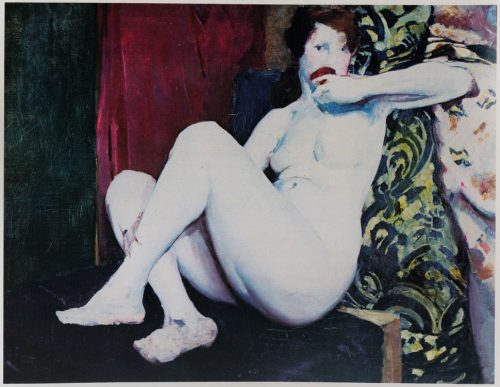

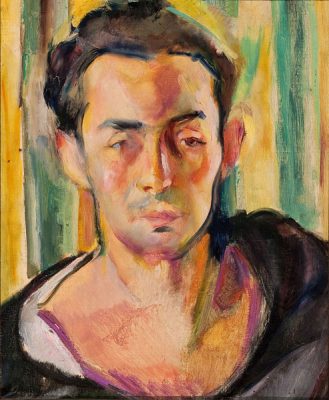

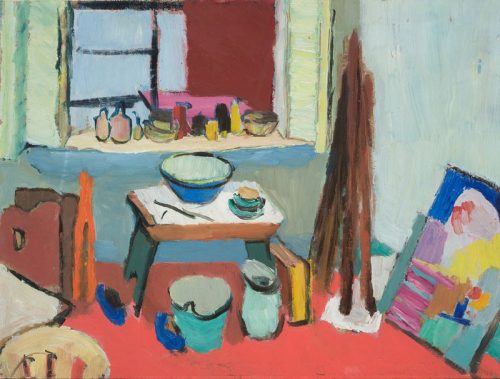

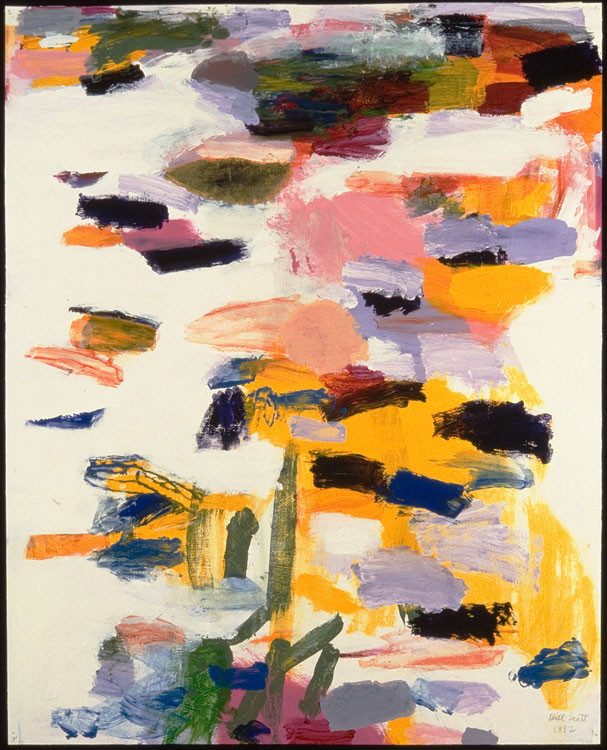

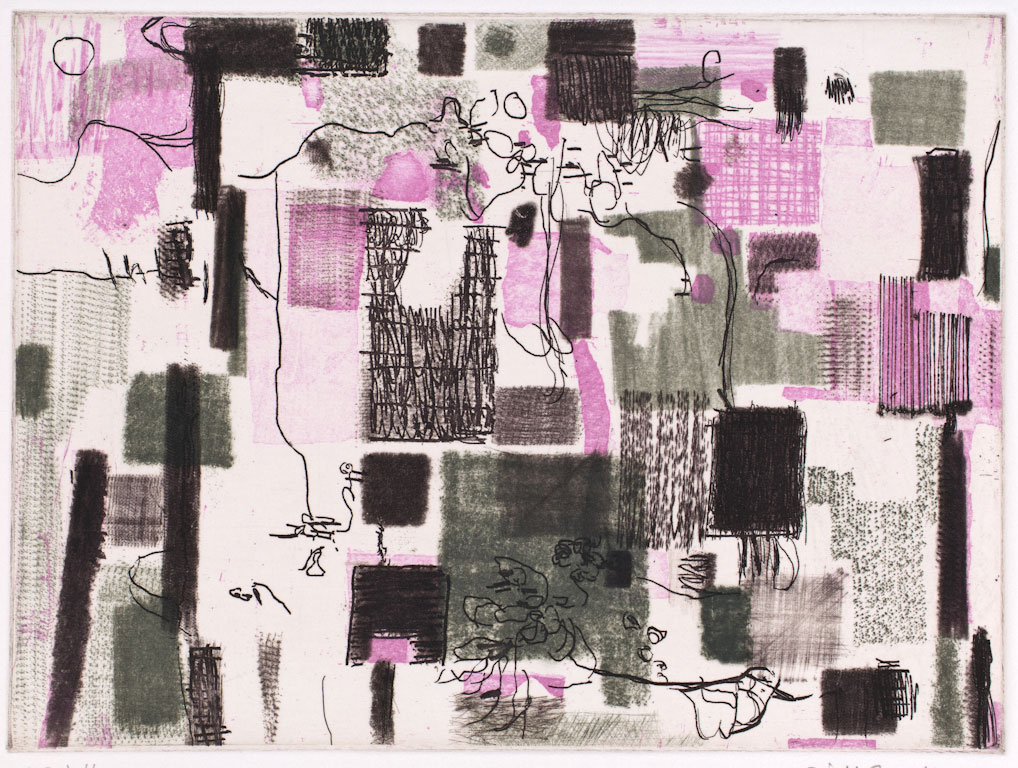

Painting from 1980 – 1998

When I was out of art school, I realized I wouldn’t be getting a teaching job. The only art-related jobs offered to me were at museum bookstores and art supply stores. Seeking employment in art galleries, I am told, is now frowned upon, but in high school, I had interned one summer and weekends at Marian Locks Gallery in Philadelphia. Later on I worked for commercial and nonprofit galleries that, I believe, proved helpful as I learned to navigate my own relationship with galleries. I also think writing all those profile articles on different artists helped me realize that no matter how someone else painted, we all have similar anxieties and hopes. In the beginning it was creative and fun. I pondered the question of whether I should try to start a gallery of my own. But I was surprised by all the jealousies and rivalries that exist between certain artists. Many of the older artists also were overly anxious with fears their upcoming solo exhibitions would look like a group show. I understand that anxiety now, because when I see my own work, I only remember how frustrated I felt making it. I’m never fully able to see it the way someone else might. After hanging one artist’s exhibition, I was anxious for her approval when she came in to see how I had arranged the paintings. She looked around and said, “Well, it doesn’t look worse than I thought it would.” Then she added, “It doesn’t look better than I hoped it might, which is disappointing.”

I continued exhibiting in Philadelphia, but concurrently, between 1989 and 1997, I had four solo shows in New York at Prince Street Gallery. My friends Iona Fromboluti and Douglas Wirls showed there. They suggested I apply for a solo show in the summer guest artist slot. I presented an exhibition of my pastels in May 1989. I had a wonderful time. Joan Mitchell sent people in to see it, and Jane Piper and Quita Brodhead came to the opening. When my parents died, Iona and Doug encouraged me to join the gallery. I’m still grateful to them for that. I had three more solo exhibitions there, in 1993, 1995, and 1997. In January 1998 I left the gallery because I felt I was a better advocate for other artists than I was for myself. It was six more years before Hollis Taggart invited me to show with him. It’s been an absolute pleasure working with him and his colleagues Debra, Kara, Stan, Jillian, Lydia, James, and Martin.

Painting from 2003 – 2017, courtesy of Hollis Taggart

LG: Do you tend to paint quickly or slowly?

Bill Scott: I never feel I’m doing or accomplishing anything, yet when I look back I realize I’ve made a lot of work. I’m usually working on ten or fifteen paintings at any one time. Many of them are facing the wall because I simply don’t know what to do next. I spend a lot of time just looking at them and don’t touch some of them for months. But I rarely abandon a painting and, if I do, I inevitably come back to it. For example, I have two canvases I started in 1992 and every year or so I paint a little bit on them before turning them to face the wall again. Most paintings take six months to a year or two to complete. Throughout the entire academic year, when I taught, my energy was focused on helping students figure out how to advance and finish their own art. Eventually it dawned on me that, even though I was working on many canvases, I was unable to finish a single canvas of my own between late September and early May. A week or two after school ended in May, I’d find myself completing eight or nine paintings in a two- to three-week period. I don’t know why that was.

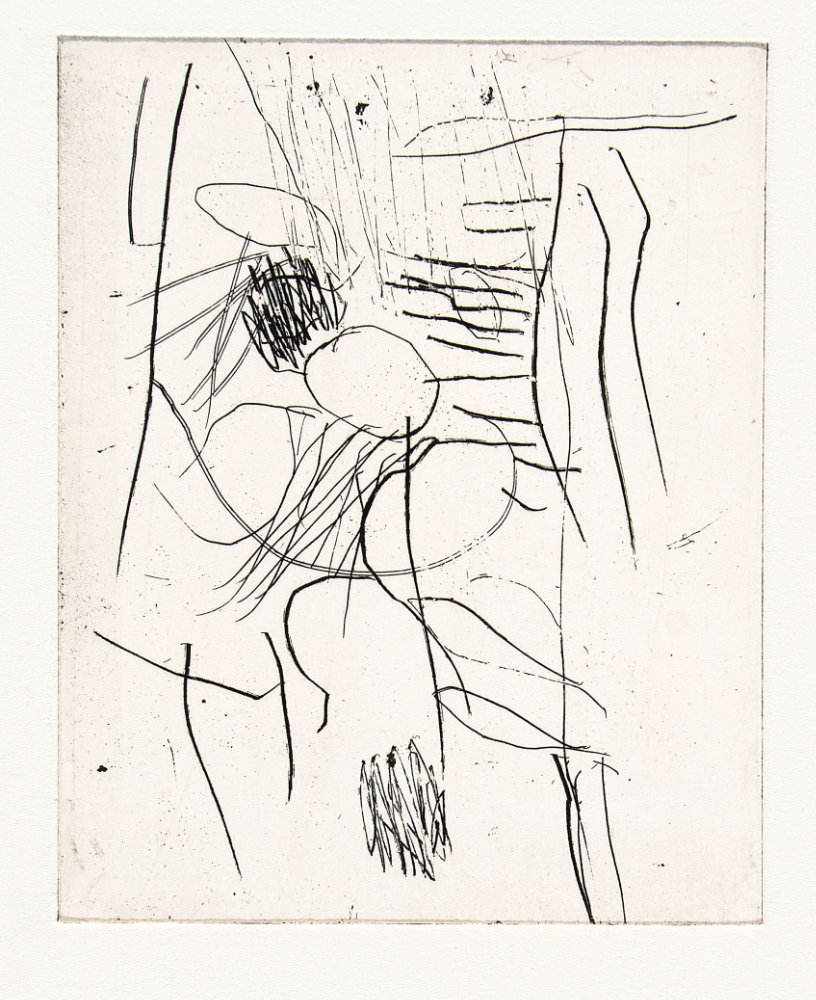

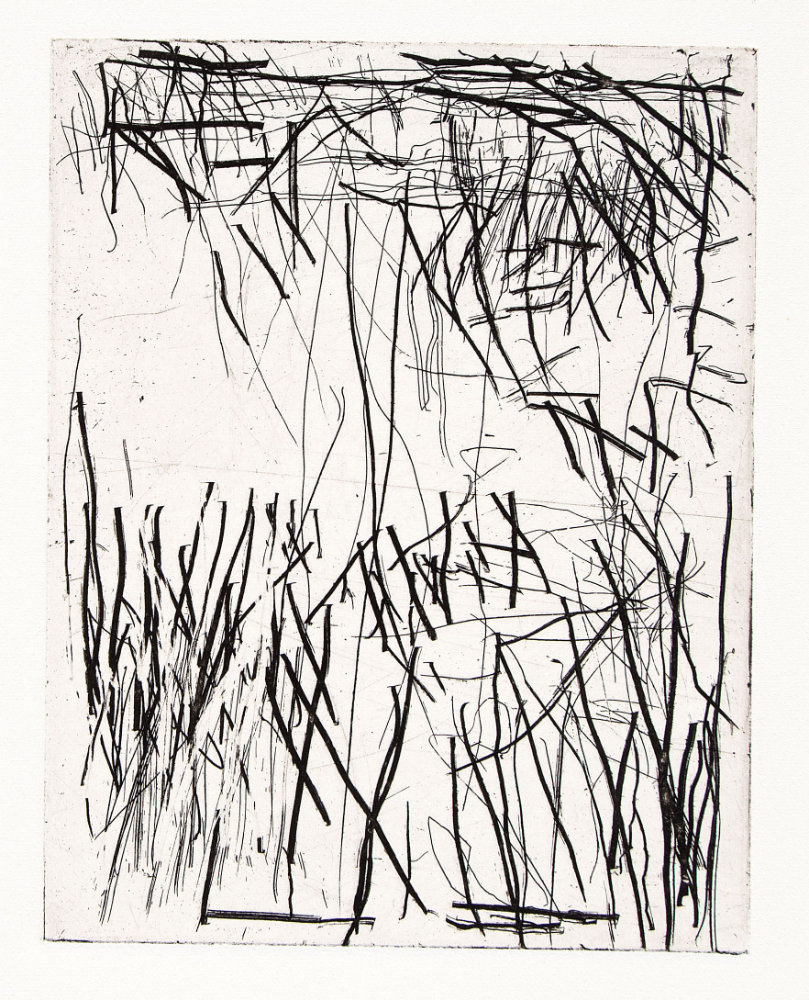

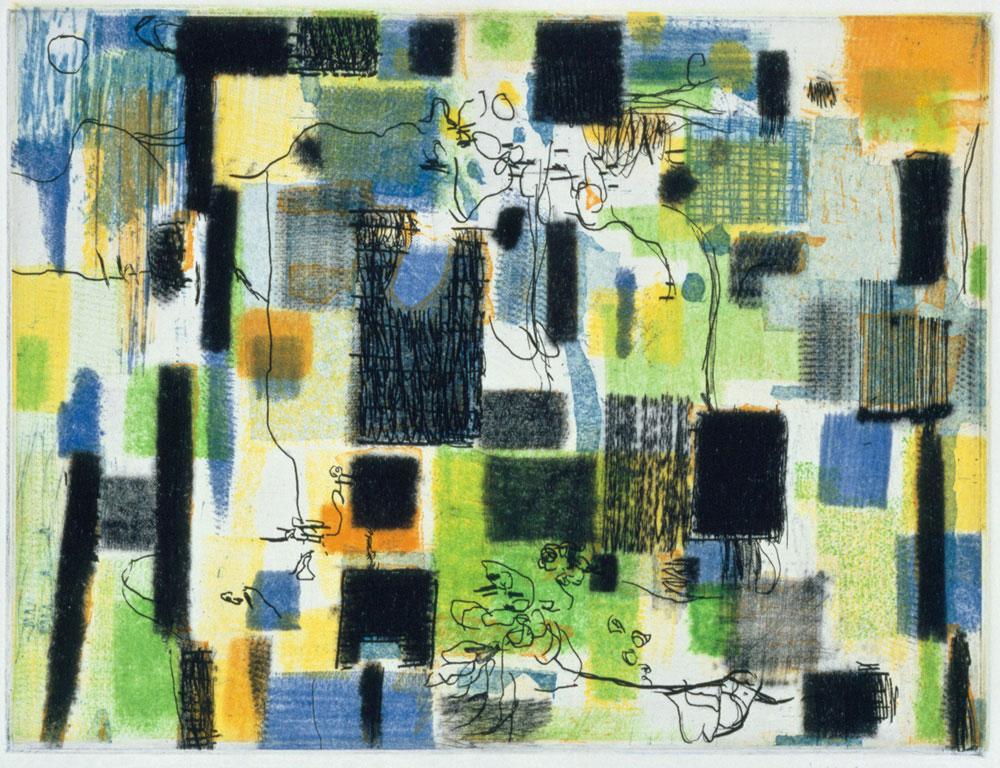

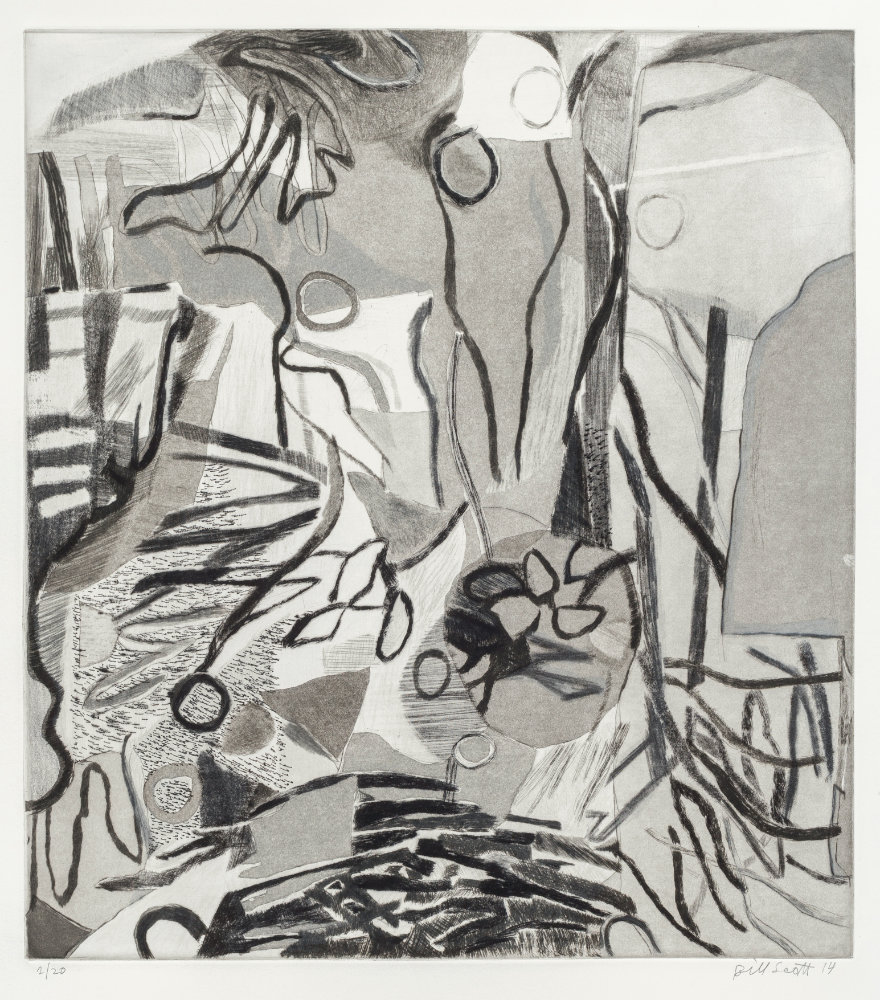

Printmaking

LG: What kinds of conversations do you have between your prints and paintings?

Bill Scott: Twenty years ago I temporarily had no studio where I could paint. I started making etchings with Cindi R. Ettinger, an artist and master printmaker, in her Philadelphia studio. At the time she was working on a multicolor aquatint with Neil Welliver and additional prints with Sarah McEneaney, Celia Reisman, Daniel Heyman, and Kevin Strickland. I wasn’t usually in Cindi’s studio when the other artists were there. But Cindi hung the different states of each print on her walls, and I learned a tremendous amount from seeing them.

Five copper plates and individual color proofs. Installation view of Bill Scott: Hydrangea with working states and color proofs, C. R. Ettinger Studio, Philadelphia. April 24 -June 11, 2014

Installation view with eighteen color trail proofs. Bill Scott: Hydrangea with working states and color proofs, C. R. Ettinger Studio, Philadelphia. April 24 -June 11, 2014

I started out making little black-and-white linear etchings. At first I sat in my backyard and, looking at the hollyhocks and other plants, drew directly on the copper or zinc. I got tired of the time it took for the etching to be in the acid bath, so I went to a toy store and bought a Dremel marketed as a way for children to write their names on a bracelet. That created a less steady and differentiated line that made me begin to think a little differently—it took me a step away from making etchings that, to me, looked like etchings.

Soon thereafter, I started working with color that opened up tons of other possibilities. Interestingly, I started to realize if I was stymied while working on a painting, I began to pretend the painting was an etching. “What would you do,” I’d ask myself, “if this were an etching?” And vice versa. At the start of working with color, I would separate the colors and not have them overlap much. In hindsight, I realize I was probably like one of those people who doesn’t want the different foods on their plate to touch. I built up to overlapping many of the colors. When making an etching it was difficult to be improvisational in the way I am when I’m painting. I had to know in advance, for example, where the yellow was going to be and where it would overlap with blue to make green or with red to make orange or with both to make brown. And things always changed.

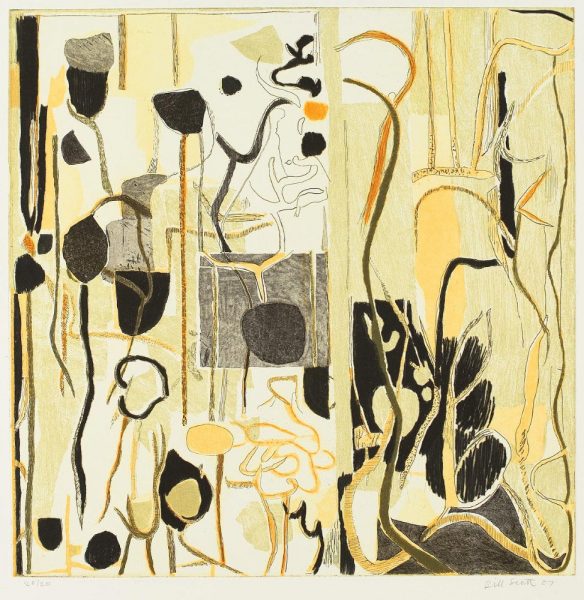

Bill Scott, Larry’s Garden: Winter, 2007, etching with aquatint, drypoint and white ground in four colors, plate: 17-3/8 x 17-1/4 inches

One of the first four-color etchings I made, Larry’s Garden: Winter (2007), I planned to make with red, blue, yellow, and black. In the course of printing color trial proofs, I decided the yellow plate would look better if it were printed in black—and it did! Now that there was a new black plate I had to figure out what color to make the original black plate. The printing inks don’t always align with oil paint colors. To see if I could try to have a print better match a painting, I started using oil paints that were pretty close to the inks: Carmine Red, Ultramarine Blue, Cobalt Blue, Indian Yellow. I love an ink color called Solferino Purple. But I could only really make it work in very small areas. Making etchings with Cindi allowed me to see again how gorgeous the medium can be. I love the authority and presence of a richly inked printed line. I think my color etchings are among the best things I’ve made and I wouldn’t have made any of them were it not for Cindi.

LG: What paints do you use? Do you look for certain attributes of the paint quality?

Bill Scott: In 2002 or 2003, when I started painting with oils again, I spoke with my friend Scott Noel. At his suggestion, I began painting with Old Holland paints, which are what he also uses. I loved them and, in using them, I began to better understand and appreciate how he uses color as both tone and color. Another painter friend, Gilbert Lewis, worked in art supply stores for decades and numerous times he suggested colors he thought I should try. He introduced me to Winsor & Newton’s Perylene Black that I love, especially when mixed with yellows or pink. He also persuaded me to try Gamblin’s radiant colors. I dislike the colors, but they’re great to mix with other colors. For example, the radiant green and radiant pink mixed together make a wonderful gray. I like the saturation in the colors made by both Vasari and by Mussini. I especially love the smell of the Mussini paints. I also have a lot of Williamsburg paints. I’m willing try almost anything. Sometimes, if I feel I’m at an impasse, I’ll go to the art supply store and buy a tube of a color I dislike. When I get back in the studio, I become completely engaged with discovering what I can do with it.

LG: The photos you posted online of a still life you set up for your class were remarkable. What do you encourage your students to look at and think about when painting something like this? What are the pros and cons of using a still-life setup like this with your own work?

Bill Scott: I’ve always been drawn to still life as a springboard for making paintings. Sometimes my paintings end up looking like still lifes, but I no longer paint from them. In the past I occasionally taught painting workshops. At those times, I liked to set up a big nonsensical still life at the center of the room around which the students painted at their easels. Those arrangements echo the color, shapes, and space of my paintings. I feel so excited when setting up the still life. I tell the students I want them to paint the most representational painting possible vis-à-vis color. I want them to focus on mixing the color so it’s accurate to what they’re seeing. I follow that by saying, “No drawing!” It’s a challenge for someone to be told that they’re not allowed to draw in an art class. They come to see how a line can be created where two colors meet. I want them to create the painting by juxtaposing the shapes, color, and space. Ultimately, I think that leads to a believable sense of what they are seeing. And, of course, they end up drawing.

In the last half of the class, I have them leave their palettes where they are, but I make them turn their easels around. They continue to mix the colors while looking at the still life. But they turn their backs to the still life when painting. This forces them to hold the image in their mind’s eye. These paintings are usually their best, and the nice thing for me is that they’re able to see that. It might sound mean, but I don’t want them to immediately know how to do what I’m asking them to do. I want to help and allow them to figure it out. I love the E. L. Doctorow quote, “Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

I always share with the students my belief that to paint is to allow oneself to feel vulnerable. I also say the best paintings are those made when the artist doesn’t yet know how to make them. Almost every time I go into my studio, I feel as if I no longer remember how to paint. That’s great! One needs to approach the process with a lot of uncertainty. At the start of every workshop, before they’ve even really looked at the setup, there’s always someone who protests. Or they basically stomp their feet and say they don’t want to paint a still life. Sometimes, I think, they’re disappointed because they expected the workshop to be fun, like one of those classes where people drink wine and perhaps flirt more than paint. These folks always throw me off balance. By the end of the class, they usually come around, paint a lot, and leave having gained the most. Surprisingly to me, they’re often the ones I end up having the best connection with.

LG: Is responding to music part of your painting process?

Bill Scott: One of the first concerts I ever attended was to see a duo named Hedge and Donna. They sang at a small place called The Main Point that was close to where I lived. They sang a song titled “Jamie,” which I still love. There’s a line that goes: “Your life has brought you places where your mind can make you happy, where your thoughts don’t drive you crazy.”

That is my own aspiration, my hope. I try to go into my studio with a calm and empty mind. Music is often able to help me to achieve that state of mind. I often, but not always, listen to music when I paint. Music may be for me what a cigarette is for friends who smoke. It allows me to pause, step back, and with a conscious mind contemplate what I’m working on. Sometimes, except for the sound of the brush touching the canvas, I prefer the silence. I never paint along to the music or attempt to make a visual image that illustrates or explains it. Now and then, I’ve stolen a line from a song to use as a painting’s title.

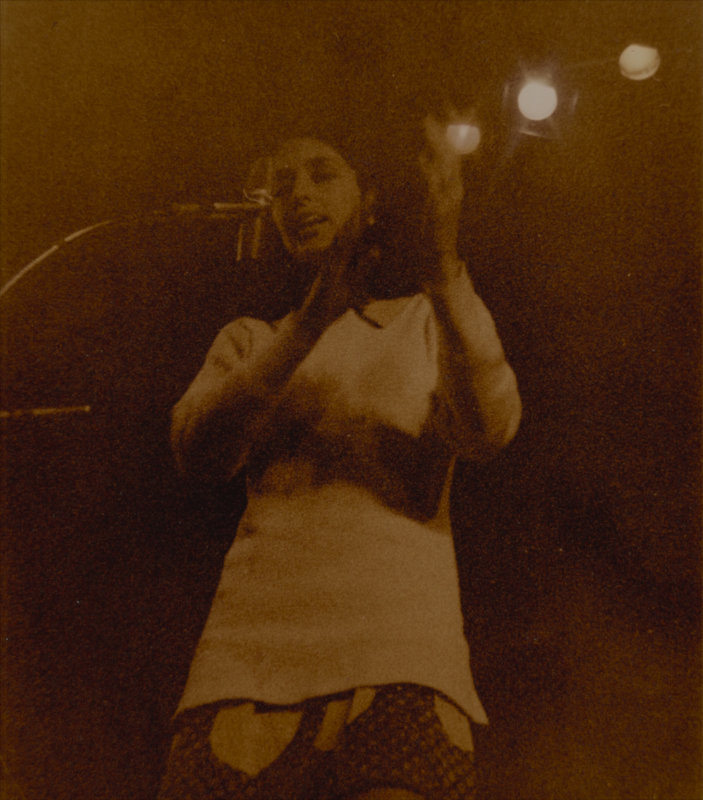

LG: I loved hearing how you sent Joan Baez a fan letter when you were 13 and you received one of her drawings in return. You included a few of her drawings in the recent show you curated at the Cerulean Gallery. Link to video of the artist talk at this show. You spoke about how she once said something like, “When she sings, she spends half the evening helping people to forget the sadness of the world and the other half getting people to remember.” You said that, for you, this was what painting was about—to suspend disbelief and then believe again.

Bill Scott: Like many others, I fell in love with Joan Baez’s songs the first time I heard one. An older friend said the first time he heard her sing was on the car radio while driving on the highway. He was so stunned, he said, he pulled over to the side of the road just to listen. I knew people who refused to play her recordings because they disliked her politics. I never understood that because, to me, her politics stemmed from an inherent kindness toward other people.

I also became a fan of Joan’s younger sister, Mimi Fariña, who was also a singer. I loved her concerts and her songs that were like bittersweet short stories: straightforward, filled with sadness, humor and anger, but totally lacking in pretension or grandiosity. For a while she sang with Martine Habib, who also had a gorgeous voice. Mimi and Martine were both very friendly. In the 1990s they came to the opening receptions for three solo exhibitions I had in San Francisco. Mimi once told me, “It takes a career to have a career: in addition to being an artist one was required to have a manager. Unfortunately artists are usually required to have both of those jobs in addition to having a salaried job so they can pay their living expenses.” It’s important advice I’ve shared with anyone contemplating a life in the arts. I felt sad as she phased out her singing career, which never took off in the way she hoped. Instead she focused on Bread & Roses, a nonprofit cooperative organization she founded in 1974 that brings free music and entertainment to jails, prisons, hospitals, juvenile facilities, and nursing homes. Mimi died in 2001, but Bread & Roses continues.

When I was very young, I did send a letter of admiration to Joan. Her aunt responded and sent a drawing. It wasn’t until I was older that I realized what an extraordinarily kind gesture that was. With this in mind, when I first worked for commercial art galleries, I offered solo exhibitions to many of the painters I had met at art school. Something in me wanted to disprove the school dean’s dire prediction. “I’ll show you,” is what I was thinking to myself. More recently I’ve enjoyed organizing group shows for Cerulean Arts, a gallery in Philadelphia run by my good friends Tina Rocha and Michael Kowbuz. A few years ago I visited San Francisco. Before going, I contacted Martine, Mimi’s singing partner, and she proposed that we meet for dinner. My friend and I met her at a restaurant and Martine surprised both of us by bringing Joan with her. Afterward Joan took us to her house and showed us her studio. She’s been painting more and more—mostly figures and portraits—since she’s stopped giving concerts. When I organized an exhibition for Cerulean last year, I invited her to participate and she sent some beautiful drawings. I was so grateful and felt absolutely wonderful. Her’s is a kindness I hope I’ve also been able to extend to other people.

LG: Speaking of being kind, I heard you talk about the need to paint something about kindness – perhaps as a talisman to ward off evil or as an antidote to our toxic times. You said, “The happier I am usually the pictures are darker but when I’m depressed they are very bright…So I’m going to be painting very bright and buoyant pictures until the end of 2020”.

Bill Scott: I paint what I yearn to see – or perhaps I should say, I paint the feeling I long to feel. A close friend was the landscape painter, Rose Naftulin, whose husband unexpectedly died when she was about fifty years old. After his death, she told me, she always felt peaceful when first waking up in the morning. A second later, though, she would remember and then she would begin to weep. Like many artists I know, contrary to how she felt deep down, her paintings exuded a buoyant pleasure. I began seeing them as her unconscious attempt to prolong that moment of awakening before she remembered. I try to do something similar. I like the W. H. Auden quotation, “Pleasure is by no means an infallible critical guide, but it is the least fallible.”

LG: I’m curious to hear your thoughts about how making beautiful things is still important for painters to make when we’re faced with the horror and outrages of war, climate disaster, and the potential collapse of civilization?

Bill Scott: I think to paint and to show others your paintings, at its core, is a way to say, “I exist.” There are so many painters from the past whose work I love and am grateful they left behind such beautiful, resilient, and timeless images. Those images also say “I existed,” and there are days when I wish I could go back in time for no other reason than to watch some of those artists painting in their studios. With that in mind, on a very deep level, I think of making my paintings as being parallel to writing love letters to an unknown future. I’m fairly self-defeating, so I follow that desire by teasing that at some point in the future my paintings are apt only to be used as flotation devices or window coverings. The world has changed so much in the few weeks since we started this conversation, I now feel foolish for saying that. I wish that all this time, instead of thinking of the future, that I had focused on painting love letters for the here and now. When I read the news, I wonder why anyone continues to paint. I know it’s what one is supposed to do, but I don’t want to paint imagery that echoes or illustrates the news. I couldn’t bear to do that. I’m at an age where I accept, reluctantly, that sooner or later we’ll all be gone, probably without a trace. I was, and remain, very moved by the end of the book Long Time Coming and a Long Time Gone, a posthumous collection of essays and poetry by Richard Fariña. His widow, Mimi, wrote, “I had a dream a few days after he died that we met and I wanted to hug him and he said, ‘You can’t.’ He said, ‘Just embrace me with your thought.’”

I love that idea: to “embrace me with your thought.” I hope someday my paintings can be that kind of a gift and that somehow, in an unknown future, someone who sees them might feel they have experienced an existential embrace.

Prince Street Gallery 50th Anniversary Catalog (scroll to bottom) with essay by Bill Scott

![[Left to Right] A color woodcut by Mitzi Melnicoff, four ink drawings by Joan Baez, and charcoal drawing by Theophilus Brown in the exhibition, An Inherently Hopeful Gesture: An Exhibition of Portraits and Figurative Works Organized by Bill Scott. Cerulean Arts Gallery-Studio, Philadelphia, April 24 - May 19, 2019 [Left to Right] A color woodcut by Mitzi Melnicoff, four ink drawings by Joan Baez, and charcoal drawing by Theophilus Brown in the exhibition, An Inherently Hopeful Gesture: An Exhibition of Portraits and Figurative Works Organized by Bill Scott. Cerulean Arts Gallery-Studio, Philadelphia, April 24 - May 19, 2019](https://paintingperceptions.com/wp-content/gallery/bs-15-baez/15_6-_3884.jpg)

Very interesting and inspiring. Thank you.

I feel lucky to have discovered Bill Scott and this insightful interview.

Cher Bill,

Je n’ai pas le son lors du visionnage des vidéos. Je vais chercher sur YouTube directement.

Merci de m’avoir envoyé le lien. Une petite fenêtre d’espace et de liberté pendant ce confinement dû à la pandémie du covid-19.

Bien à vous,

Claire, du musée d’Orsay

I think I may have seen a card for one of Bill’s shows, maybe twenty years ago, and have followed his work by way of the Taggart shows since then because I love his work…

It’s wonderful to get this back story and understand his development!

This is my first visit to Painting Perceptions and I’ll be back—Thank you, Larry Groff!

Thank you, Larry and Bill. I really enjoyed the whole article and the thoughts. I can’t imagine what young painters are going through in the time of social media and the internet as they try to develop and find their voice. How lucky that Bill got to stay at Joan’s before the age of social media. And to be in touch with Joan Baez, in the day of letter writing! What a life you’ve lived, Bill! The recent work, especially, “An Inherently Hopeful Gesture” looks great.