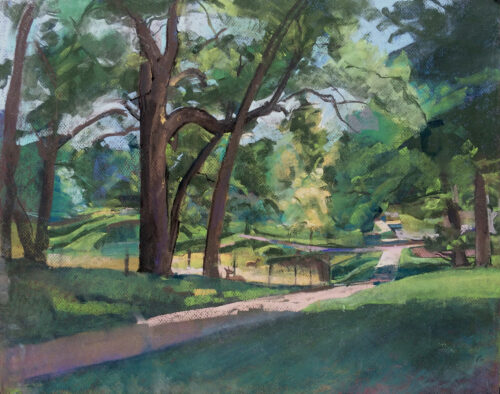

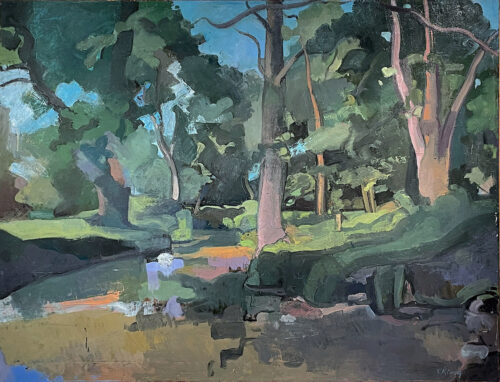

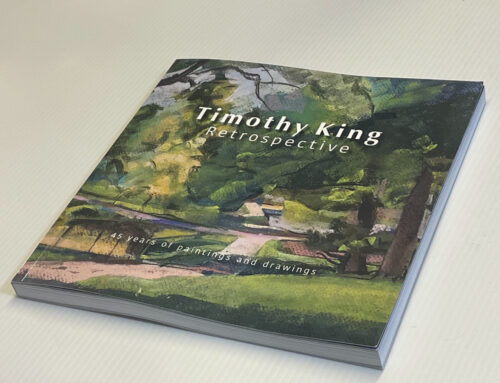

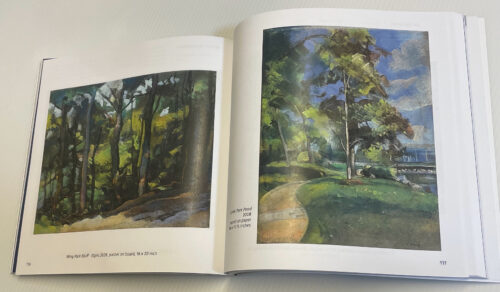

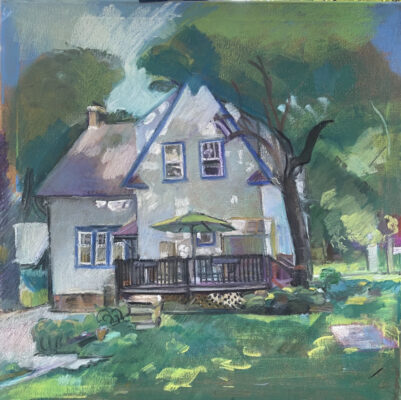

I’m pleased to present this email interview with the Elgin, Illinois-based painter Timothy King. I had wanted to find out more about his life and work after seeing his work online and when he wrote about his studies with Stanley Lewis for my interview with him a few years ago. I was impressed by his leadership of the Midwest Paint Group, which has held several terrific exhibitions that often featured the work of modernistic mid-western painters who work from observation in some way. I’m especially pleased to share this interview as his 45-year retrospective at the Kishwaukee College Art Gallery in Malta, Illinois has just been shown. I was grateful to receive his gift of the stunning print catalog for this show, where example after example of his paintings reveals the depth of his emotional engagement with his chosen motifs from nature and compliments the intensity of his painterly response and compelling compositional structures. King pays forward the tradition of modern perceptual painting in the spirit of his mentors, Wilbur Niewald and Stanley Lewis.

Excerpt from the Timothy King Retrospective catalog essay, A Life of Visual Sensations, by Stanley Lewis

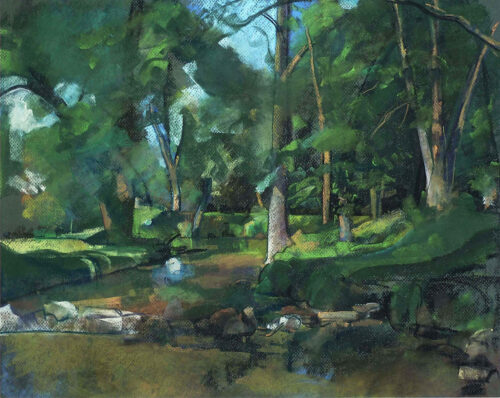

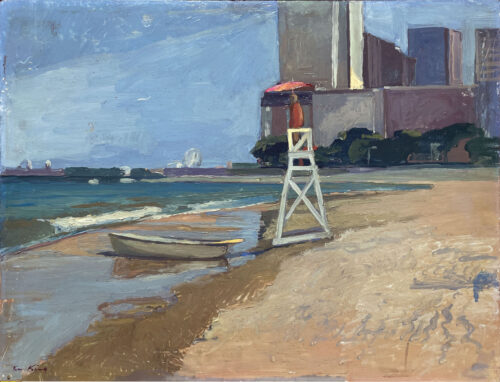

“I keep looking around for other painters who are hooked on setting up their easels in front of trees, bushes, houses, sidewalks, clouds, etc.–the urban landscape. There are only so many painters who are interested in this. For one thing, it is very inconvenient—lots of stuff to carry and something that can go wrong with the weather. Tim King has been plowing away at this for 40 years, consistently working on his visual concepts. Setting up and painting in every place he is living and trying to get through that day, this show covers all those places and times.

The same situation existed for every outdoor painter who has done this at any time. Corot, Cézanne, van Gogh, Wilbur Niewald, Rackstraw Downes, and Tim King. You look out there, set up to paint, and say, “this is impossible. There is no way I can paint this.” This retrospective shows a lifetime of such outdoor painting.” – Stanley Lewis

Bio from King’s website timothy-king-studio.com/,

“King studied at the Kansas City Art Institute with Lester Goldman, Wilbur Niewald and Stanley Lewis. King’s work has been exhibited in Chicago, locally and nationally, notably in New York at the Bowery Gallery, as well as at the Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art in St. Joseph, MO. He is a founding member of the Midwest Paint Group. His work is in the collection of the Sheldon Swope Museum of Art in Terra Haute, IN.” He is a member of the Bowery Gallery in NYC, had shown work at the Kate Hendrickson Gallery, Chicago, IL. He taught at Kishwaukee College, 2014 – current), Professor of Art & Design see his CV for more

Larry Groff: What led you to put on this 45-year retrospective?

Timothy King: I needed to look back, catalog my artistic life, and consider my achievements. I’m coming up on ten years as an adjunct professor at Kishwaukee College. Other faculty had done shows there over the years, so it was my turn. Initially, I wanted to do a retrospective; unfortunately, the pandemic delayed the show until now. When the gallery reopened, the manager wanted to change the plan to do a trimmer, current works show. Unfortunately, last year I underwent heart bypass surgery. When I fully recovered, feeling better than ever, I decided this show had to be a retrospective. I also considered the Kish Art Gallery. It’s a unique space; the architect designed it as a gallery with ample square footage and a vast open viewing space for art.

LG: Your retrospective catalog must have been quite the undertaking. The photography, color correction, and layout must have been much work. Did you do this yourself? Would you recommend using Amazon print on demand?

Timothy King: I designed and published my catalog with 195 pages and 175 artworks, of which I exhibited 134 pieces. I had to re-photograph most of the art. My colleague Loretta Swanson wrote the introduction, and I worked with Stanley Lewis to get his essay. I included ten poems by my wife, Elizabeth Stanley King, and Walter King, my brother, who wrote an essay. Getting it all together for the catalog was a tremendous job, but I’m also a 37-year veteran graphic designer.

Amazon Kindle print-on-demand is a fast, affordable, quality way to deliver an art book. It usually takes a day to go live on Amazon and for sale. Delivery takes three days. The quality is close to Blurb.com, the best in the industry, but a lot less expensive than Blurb.

The catalog is available on Amazon, from this link – Timothy King Retrospective

LG: What led you to want to be a painter? I understand your brother, Walter King, is also a painter. Anything interesting to say about your family?

Timothy King: My older brother Walter and I were artistically talented. Mom was an artist, so we got a lot of encouragement. During my high school years, Mom and Dad opened an arts and crafts store called the King’s Glue Pot in Tulsa. Mom taught art classes, and Dad made woodcraft products. He did picture framing, too, and taught me how. We all helped run the store. Walter and I were each top high school artists, but I started college first at Columbus College of Art & Design. Walter is four years older and didn’t pursue college, so I entered him in the CCAD new student portfolio contest after Christmas break. The first he knew was in receiving his scholarship award. When I decided to study painting because I always loved it, my painting teacher recommended I transfer to Kansas City Art Institute for its reputation as a painting school.

Walter studied Illustration at CCAD but was also a serious painting student. He studied with Nathanial Larrabee. After getting our BFAs, Walt went to Boston University, and I went to Tulsa University without any mentorships. I was still working from my KCAI accomplishments and rejected what the one TU painting professor offered. After 30 years, Walter retired Emeritus Professor of Illustration from CCAD. I’m an adjunct professor at several schools and teach full-time. Becoming painters, somehow, was ordained for both of us. We’ve done three two-person exhibitions in Columbus, Chicago, and Cordoba, Argentina.

LG: You went to Kansas City Art Institute in the early 80s and studied with Wilbur Niewald and Stanley Lewis; what was that like for you?

Timothy King: I was at KCAI from 1976 to 1980. I studied drawing and then painting with Wilbur Niewald for one semester of painting and a couple in drawing. I appreciated his ability to get you to see the model in that north light studio. Wilbur was chair of KCAI painting for a long time and built that department into a fantastic painting school. He brought in younger painters like Stanley Lewis and Lester Goldman. Altogether there were seven painting faculty, and I studied with five. I was with Stanley Lewis for three semesters and a couple extra for drawing. I got to know Stanley best and formed a lasting friendship with him. I kept in contact with Wilbur and visited him several times before he passed last year. I studied at four schools, and none were as great as those days at KCAI.

LG: What did you learn from Wilbur Niewald about painting the landscape and from life that remains critical to your current practice?

Timothy King: While I learned about landscape painting from Wilbur’s ideas and by looking at his work, my landscape practice developed during grad school in Tulsa. I did one unfinished landscape with Wilbur, but my time was spent primarily inside the studio, working from the model and still life. From Wilbur’s teachings, landscape painting was no different than still life to me. Wilbur taught abstraction through his idea about perceptual structure. He taught me that a convex and concave experience envelopes and weaves throughout space and form. I still see Wilbur lace his fingers together as he describes it. Wilbur also taught me tonal color. I remember painting a lovely glowing nude with soft, neutral warms and cools when Wilbur grabbed a brush, mixed up a brilliant red, and plopped a stroke on the nude’s face. That splash keyed up the whole painting five times. So many people think being a colorist is all about bright color, but Wilbur taught me a finer sensibility which I’ve tried to carry into my landscapes.

LG: What was Stanley Lewis like as a teacher?

Timothy King: I used a lot of ideas from Stanley, and he inspired me to write about those ideas and study drawing and painting analytically. I’m a theoretical thinker, so he encouraged me to write about painting. I’m a visual thinker, so the ordering of words presents me with great difficulty. I did go on to write my MA master’s thesis on binocular image formation in drawing and painting. The paper is posted on reaserchgate.edu along with my MFA thesis. In his classes, Stanley created different controlled experiments for each student. Stanley had me working on his “Two-Table” theory and had me make mockups from Dutch still lives. I would set up two tables tipped oppositely, in forward and backward tilt. The table positioning is more complicated than I’m explaining, but the point is that the painting captured the appearance of objects on top of one table, not two. In these setups, there was a reversing of the illusion of things positioned in space. The foreground and background objects in the compositions are juxtaposed in relationships. It was a play on the painter’s sense of form ruled by intuition over expectation. I continue to work on this idea in my landscape painting. Stanley and I have a shorthand language about ideas on painting. I’ve heard many more of Stanley’s drawing schemes than I’ve ever understood. Sometimes, he’d refer to the “Painter’s Form” as if there were ideas ingrained in the tradition of painting. I have always appreciated that Stanley taught to the individual in his classes and tried to help each find a unique knowledge bracket to work off. I’m sure he came up with teaching angles I’ve never seen. He is a remarkable teacher. I wrote about some of Stanley’s teachings for your interview with Stanley Lewis. Here is the link. MY STUDIES WITH STANLEY LEWIS, By Timothy King (scroll to end).

LG: You later got a MA in 1985 and then an MFA in Painting in 2006 at Northern Illinois University. I’m curious to know why you earned both the MA and MFA. Was it so you could teach in public schools?

Timothy King: I went back for my MFA in 2003 to teach college art. I got my painting MA in 1985 but had no support at Tulsa University, so an MFA from a different school was more appealing at that time. Stanley referred me to Yale, and I interviewed as a finalist MFA candidate. But it was a no-go. Then, Stan sent me to Parsons, where Leland Bell and Paul Resika taught. Parsons awarded me their top MFA scholarship. But ultimately, New York was too expensive. Not going to Parsons is a regret. I had one more chance at Northern Illinois University in 2003. I graduated in 2006 and went right into teaching. I’m a full Professor rank, part-time, at Kishwaukee College teaching design. In addition, I teach drawing and design classes at several Colleges as a full-time living.

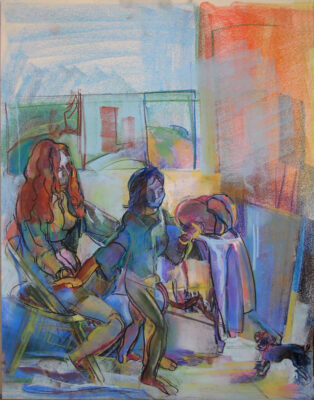

LG: Your earlier work shows a love for painterly expression like that seen in Oskar Kokoschka’s work or the Bay Area Figurative painters such as David Parks and Richard Diebenkorn. Later, your work emphasizes a more tonal palette with light and value carving out the 2-D designs. In what ways do you feel your work has evolved over the years? What has been most important with your compositions, and what are your most important influences?

Timothy King: I have always painted with expression and liked Kokoschka’s landscapes early on. I was fortunate that I met with a former Kokoschka student giving a talk at Tulsa University. He concurred that Kokoschka thought himself a classist, not a German Expressionist. As for my Diebenkorn similarities, I found his flatness and simplicity were approachable. I’m still not a David Park admirer, but Walter appreciated him, so I paid attention. Walt studied with James Weeks and Nathan Oliveira at BU. I worked in sophomore painting at KCAI with Hal Parker, who studied under Weeks and Park at the San Francisco Art Institute. Walt and I have a fair amount of Bay Area school in our DNA. So, Walt and I shared a dialog about our respective teachers that worked to our advantage. Here is a link to Walter King’s website:

That Bay Area sense of painting got me early on. In high school, I saw my first Wayne Thiebaud painting of a woman in a bikini at Philbrook Art Museum. Many see the Balthus influence in that picture of my wife leaning on a gravity chair in her underwear, but the solidity of that Thiebaud painting influenced me just as much. Helion, Leland Bell, Derain, and Balthus were my most important influences. Of course, I copied from the old masters as one should.

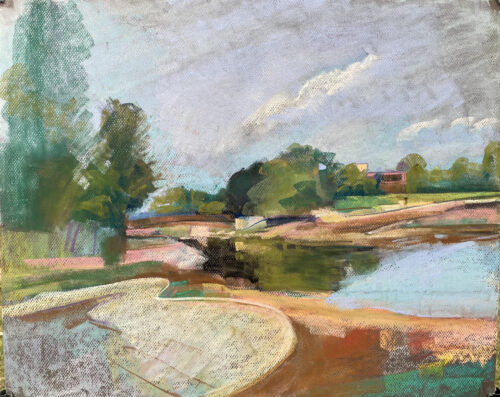

Becoming a Landscape painter, I looked additionally at Matisse, Cézanne, Courbet, Corot, Constable, Golden Age Dutch landscapes, and Italian Baroque landscapes. I’ve always believed in those painters. I’ve worked with a Matisse early and Fauvist color, but mostly I work in a solid chromatic tonal range. Natural color suits me, but if you look, natural is not quite at all simple. I like being free to move back and forth in color approaches. I’m trying to grasp a classical construction of form and color. I think I’ve been evolving since my studies with Stanley. I have seen my development in three logical stages, with perceptual painting widening my visual expanse of space.

- Peripheral Vision work; the idea for a painting and drawing through a frame with the left eye on the scene and the right eye on the picture.

- Binocular Vision work. Also, a frame-based idea, the use of both eyes triangulating on the subject in the frame.

- Binocular-Peripheral-Fusion work. My current work combines the first two experiences where I’m simultaneously inside the frame, rotating my head 180 degrees. It is a five-point spherical conception, but without the typical curvature other painters utilize.

LG: How much do you plan out a painting beforehand? Do you make studies, or do you work it out on-site?

Timothy King: I have various modes of working. I like planning a landscape, but I will respond spontaneously to a view of where I end up. Sometimes those spontaneous situations teach me to be open to new ideas. I work out ideas for plasticity in compositions. What angle do I want to view the scene? How is the slope of scenery moving the space, and do I want to reverse that slope in my painting to make better sense of the forms? Usually, I go with one of several reversal approaches. My work is always a game of playing against visual expectations. I’m working more on using my on-site work as preliminary to studio paintings. I’ve learned doing the studio landscapes that I need to increase the information I capture when working on-site. The process has become a feedback loop between my studio painting, plain-air landscapes, and life studies. As I get older, I want to work more on studio paintings, but it requires me to intensify my observations in the field.

LG: I often ask painters why do you paint from observation; so I’ll ask you that too, what are your considerations about this? What does observation offer you that working from memory, studies, or invention can’t provide?

Timothy King: I prefer directly observable situations and on-site work because I’m interested in my visual perceptual process more than invention from imagination or fantasy. I don’t observe for appearance as much as to see and feel the sensual abstractions. There is a natural formation of the picture that is different when working from invented and memory compositions. Working from life helps to remove me from outside art styles and their influence. Painting from life filters out the imitation of others. Of course, I’m always looking at other painters, and I like seeing how they invent and use memory in their work. But working that way is less successful for me. Yet, I conceive objects like tree branches or a person directly from my imagination. I like inventing skies in the studio work. Sometimes those inventions stay in the finished piece. The innovations inspire further life studies needed to do the studio compositions. Mostly, I’m trying to free my mind in nature, working directly.

LG: Do you use a limited palette? How important is matching the color you see in nature exactly right?

Timothy King: I work back and forth between a full palette and a limited palette. Sometimes I’m lazy, and I start with black and white. Then I go into brown and green making it a Grisaille study, then adding blue and yellow. I react to color as I go. I’m not formula driven. The landscapes start with rough approximations, but I always seek a better color or tonal space. I want to avoid apparent local color renditions. I prefer atmospheric and indirect colors and look for unexpected color contrasts. I enjoy how a color starts interacting and changing in the color space.

LG: When you paint outdoors, especially with premier coup-type painting, what are some considerations for evaluating the work in progress?

Timothy King: I’m interested in structure and form primarily. These are abstractions from visual experience; the spaces and shapes create interwoven rhythms. It is the way I trained myself to inscribe binocular and peripheral relationships. I always aim to set up a pictorial space with interlocking shape reversals. I tune in by flipping reality away from my preconceptions; when I hit that zone, I don’t recognize anything except the forms and the abstraction. When I’m there, I’m feeling not evaluating. I’ve learned not to judge progress because painting is intoxicating. I’ve learned that my rational faculty is distorted and not as realized as my moment-to-moment intuitional sensation becomes while working.

LG: How important is being faithful to what you see in terms of measurements, angles, and details as opposed to what you think the painting needs in terms of composition?

Timothy King: Measuring and sightseeing approaches are mechanical and academic to me. So, I use rectangular relationships instead. It’s a Mondrian approach, but I have a Soutine sense too. I’m drawing from the compressions and expansions of an anamorphic experience. Angles are essential to hook the space, especially when skewed in the reverse of what you’d expect. Placing the background into a frontal plane initially changes the shape and scale relationships. I’m always trying to merge depth into the picture plane and reverse meanings between the front and back, top and bottom. That’s what I consider composition. I’m capturing my moment in my visual relational system.

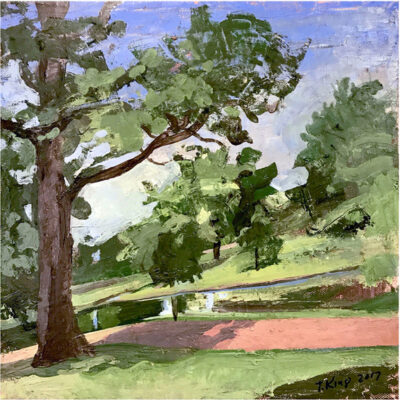

LG: I especially enjoy looking at the trees in your paintings; they seem more about capturing the lyrical movement through the picture and the design than simply describing the trees that happened to be there, not unlike how Cézanne would use the trees to structure his painting.

Timothy King: I love painting tree canopies and didn’t realize most landscape painters avoid that subject because trees are so complicated. I think about how Cézanne and Courbet accomplished painting in the tree canopy. They are among the best at it. Establishing the tree’s architecture is essential to visualize and memorizing dominant segments for significant progress. Looking back and forth causes disorientation. I’ve found myself detailing in the wrong section. I’m setting up the rhythms to create depth from my binocularity, and I use triangulation to find a blue-sky breaking through the green. The abstraction of spaces and shapes is musical to me. And once a melody flows, I can more easily get into the canopy’s complexity.

LG: When you go out to paint, what goes into your decision to use pastels, watercolors, or oils? Do you experiment with different techniques, supports, media, and such?

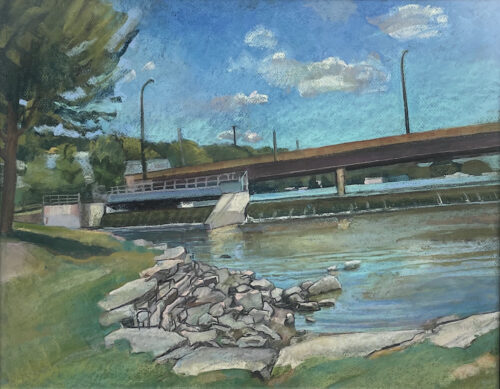

Timothy King: I’m not too fond of watercolor. I’m not like Cézanne at all. He painted in oil and watercolor revolving around the white ground to set up his light. That’s something I’ve always admired. But I use white and black in watercolor to tint and shade, and the paper’s white be damned. When I’ve experimented with mediums for oil painting, I’m concerned with drying times. I need wet paint to blend and mix on the canvas, but I also need to add bright colors over dark without muddying, so I like drying mediums. I’ve used acrylics that key my color up, and I see myself returning to them more. I love using casein paint working small. They feel and look like oils but have fast-drying qualities like acrylic. As close as I get to watercolor is gauche, which handles like casein paints, and you can rewet and blend wet over dry. I’m working on canvas, but I did work on panels for a period. I prefer oil-primed wood panels with a tan tone. In working with pastels, I’m using chalk and oil pastels. I prefer square hard pastels like the Prismacolor Nupastel brand. I use a workable spray fix to form a crust every 30-45 minutes. I use toned pastel-matt boards and toned pastel paper of various warm and cool grays. I don’t usually blend or smudge except in the underlying layer. I want the color from below to filter up to the top in little chromatic specks. I love the serendipity of chance.

LG: I understand that Jean Hélion influenced and informed your work; his writings and paintings also influenced Stanley Lewis. You had Stanley painting and sculpting in an abstract and been involved in writing a short book about Hélion, Twelve Ways of Looking at a Painting: An Homage to Jean Hélion and Le Grand Luxembourg.

Timothy King: Stanley showed me how Hélion drew using a curvy rhythmical structure. Helion’s form seems to distort space around and through those figures of people; this is not the usual way of drawing accurate contoured outlines of things. Helion has an a priori reality used to construct forms, which hooked me to Hélion’s abstract paintings. Lester Goldman first showed me Helion’s geometric abstracts with strange, distorted shapes with no apparent geometric identity. I learned that Hélion developed weird short curving shapes in little signets of abstract structure. If you look, you see them in his later work, realist still life, and figure paintings. Hélion worked off those conceptual building blocks from his abstract period to build his art. I’m the opposite of how Helion worked. He worked from the simple to the complex, and I’ve never figured out how to do that. I’ve always wanted to work from the complex, to find those strange forming Hélion-like building blocks within some essence of my perception. I teach a two-dimensional design assignment based on Hélion’s little abstract motifs. Hélion is a significant and overlooked painter.

LG: What is the community of painters like where you live? Are you able to connect with many other artists?

Timothy King: It is lonely here in the Midwest. A friend described the Chicago art scene as all spiders. It’s a fun idea. I enjoy seeing the Chicago art scene and love having conversations with my friends about contemporary art. A few weeks ago, I had a great conversation with my MFA nephew Daniel King at the Chicago Art Institute, whom I don’t often see enough. I have painter friends in Chicago, but we need to get together more. I have the Midwest Paint Group friends and new acquaintances in the Bowery Gallery. I’ve had regular contact with Stanley Lewis and my brother Walter.

LG: You were the Director of the Midwest Paint Group for several years with several shows. What about your experience with this that might be interesting?

Timothy King: I’m still the Director of the Midwest Paint Group. The group is currently in a post-pandemic slumber. I created the MPG website around 2000. It was one of the first Internet art groups back then, other than the New York cooperatives like the Bowery Gallery and Zeuxis. We got some extra attention after I posted a portfolio of Stanley Lewis’s art when he had no internet presence, so I started him online with a retrospective from scans of his slides.

In 2004 I made a Chicago cooperative gallery connection and arranged the first MPG exhibition. Our membership evolved from several KCAI grads. Mike Neary and I are the two remaining six founding members. Of the 11 current members, only three are KCAI graduates. The rest are from a broader spectrum of schools. We all share an essence of what we find exciting about painting. We are now more geographically spread out beyond the Midwest, but all share a vital or long-term connection to the Midwest. The group has done numerous museum and university exhibitions, amongst other venues in the Midwest and East.

Here is the link for our group. midwest-paint-group.us.

LG: Gabriel Laderman had been involved with your group for a time before he passed in 2011. How did he become involved? What do you find most interesting about him?

Timothy King: Gabriel Laderman searched for images of Stanley Lewis paintings for a show he was planning and found the Midwest Paint Group website. He started writing some members and befriended me. Gabriel wrote the catalog essay in that first MPG show. Gabriel called us post-abstract figurative painters, and the show was then named Post Abstract Figuration: The Midwest Paint Group. Gabriel met up with Walter and me at the MET years ago. He immediately began talking about his favorite paintings, telling us his stories. I did my Invitational show at the Bowery Gallery in 2006. Gabriel got over to see it before it closed and wrote me a long letter with an in-depth review of his experience. We finally got Gabriel to agree to show with the Midwest Paint Group what became, Realism and its Discontents at Wright State University and Manchester University (2012). Unfortunately, Gabriel passed away before the exhibition. We got three of Gabriel’s’ paintings and featured him as our special guest.

Larry, the last question you asked me about was what I found most interesting about Gabriel Laderman and I didn’t answer directly; even though I commented enough to show why I was interested in his ideas and his art. That was one part I cut off for the sake of space. Lester Goldman introduced Gabriel to his students along side the other realist and figurative painters showing in New York in the 1970’s. Laderman, Bell, De Niro, Matthiasdottir, Bailey, Anderson, Kresh and many more who were all acquainted to each other. Lester provided those artists as hero’s for us young students. We didn’t use the term post abstract figuration but we knew how these figurative painters had come out of the abstract expressionism schools or like Bell more from the Helion and Arp European plastic abstraction influence. So I knew and appreciated Gabriel’s artistic linage including his study with Hoffman, and I liked his realist and naturalist work. I had a book on landscape painting with one of his works that impressed me. But after my days at KCAI I didn’t see much about Gabriel’s art and I was very isolated in Tulsa and Chicago from the New York art world. And the art magazines seemed to have moved away from that New Realism and on to postmodernism. The Internet wasn’t a thing until later in the 90s and it took awhile before all the currently available art imagery was online. When I got that first email from Gabriel it was quite literally a shock to me. I never even met any of those painters Lester had shown us. I hadn’t gotten to meet Leland Bell though I did see him speak at KCAI.

What meant a lot to me was Gabriel would look at my paintings and drawings and talk to me about them in detail. And Gabriel had all kinds of history stories about the art world and personal experiences with famous painters like Uglow and Guston. I wasn’t really being mentored by anyone except Stanley Lewis at that time and Stanley wasn’t on email or the internet. Gabriel was quite technologically adept so I had more regular communications including phone conversations with emails. With Stanley, I would call as frequently as it seemed he had time between his teaching schedule, travels and his strict daily painting regiment which I tried to respect. So Gabriel filled a gap in that generational seniority I’ve always wanted and probably needed for their experience and wisdom. I used to be able to connect with Lester Goldman on my trips back to Kansas City that same way. I never had that with Wilbur Niewald until I got to work with him on the Midwest Paint Group Figure exhibition catalog in the 2010’s. After that we reconnected and had some interesting phone conversations and visits at his studio in KC. I’ve gone on to keep my connection with several other mentors. I was close with Ron Weaver who joined the Midwest Paint Group. Ron was a studio mate and friend of Stanley Lewis at Yale. His passing was a blow to me. I’ve had a similar connection with other painters like William Barnes who ran the painting program at William and Mary College and Bill White who is also in the Midwest Paint Group. I was close to my father and when he died I really saw how significant all these mentors have been to me as a painter and as a person.

Great interview !- and thank you for taking the initiative to form the Midwest Paint Group and for the dogged persistence that has kept it together.