I’m delighted to share this new interview with Peri Schwartz where she talks about her background and process as well her studio explorations with color, space and composition. This September she has a solo exhibition titled Color and Process, at the Gallery Naga in Boston. A previous interview, given by the writer Cody Upton was published on Painting Perceptions in May 2013 can be read here.

I am particularly attracted to the vibrancy, clarity and resonance in these new works. Schwartz studio investigations arrive at just the right tones for these color shapes surrounded by space and light but also leaves behind residual clues of where her journey took her; how colors and shapes were changed and shapes reformed in her open and painterly applications of paint. A formal movement which balances exactitude with lyricism. The bottles and studio fixings are just a starting point, the true destination is in achieving a balance and unity and artful resolution.

In an essay for the 2010 Page Bond Gallery exhibition catalog Lulan Yu wrote:

…Though making works of art is a thoughtful and deliberate process for Peri Schwartz, it also is one that involves much doing and re-doing. After she has arranged objects for a still life or interior, she often rearranges them while she is working in order to resolve problems and achieve her desired outcome. She also is carefully attuned to the effects of light and color that occur from the arrangements of elements in her works; she experiments by moving bottles and jars to different positions, creating subtle changes in the value and color of the liquids they contain. Although Schwartz seems to enjoy the unpredictable nature of creating works of art in this way, she is very sure and deliberate in her intentions. As a result, these seemingly quiet, contained still life and interior pieces have a dynamic, intriguing quality that invites the viewer to thoughtful contemplation.”

Larry Groff: Can you tell us something about your latest body of work and your upcoming show at Gallery NAGA in Boston? Does your new work continue with the theme of arrangements of light and reflections from transparent colored liquids in your studio space?

Peri Schwarz: My new work uses the same elements that have been my subject for almost twenty years. The difference is that in the early Studio paintings it looked more like an artist’s studio, with canvasses leaning against the walls and stools with books piled on them. In the more recent Studio paintings, the books are shapes of color with no bindings to indicate they are books. The canvasses have now been replaced with wooden boards that I paint with sample colors from the hardware store. I’m still captivated by the color I get from liquids in bottles and jars and how they are reflected on a glass tabletop. The grid that I have been using in my work for over thirty years is as important as ever.

LG: In previous interviews you’ve talked about the influence of Diebenkorn and Morandi on your art. What aspects of their paintings have impacted you the most with your current work?

PS: I love Morandi but in this group of paintings I’ve been looking mostly at Diebenkorn and Mondrian. For example, in one of Diebenkorn’s still lifes, I was especially drawn to the orange/blue relationship and how he looks down on the table. In Diebenkorn’s Berkeley years the subject and space are recognizable, giving it a more realistic feel. I’m striving for the same balance of abstraction and realism. It may be more difficult to see the connection with Mondrian. When I’m arranging the colored rectangular boards on the back wall I’m thinking of how he used color in such perfect proportions in his paintings.

LG: Would you call yourself a formalist? What does that mean for you?

PS: Here is where I admit I didn’t exactly know what a formalist meant when I first thought of this question. I looked it up and found this definition–Whether an artwork is a pure abstraction or representational, a formalist looks for the same basic elements and judges a painting’s value based on the artist’s ability to achieve a cohesive balance in the composition. Based on that definition I am happy to be called a formalist. About the same time I read your question I found this recent article by Jed Perl in the New York Review of Books. I know I don’t easily fit into representational or abstract art. I’m obsessed with getting every proportion right as I observe it. At the same time, I am thinking how is this fitting into the size of my canvas and would moving an inch to the left or right improve the composition.

LG: You likely got a strong foundation in traditional painting during art school. Did your experience at BU back then also encourage modernist approaches?

PS: I don’t know if all your readers know that we are both BU alumni. It was rigorous and intense and I loved it. Figure drawing, anatomy and tonal painting were the backbone. There are three professors that stand out in my mind for their interest in abstraction: Joseph Ablow, Jim Weeks and Robert D’Arista. All of them worked figuratively but emphasized how important the abstraction was in painting.

I loved Ablow’s class in composition. He had studied with Albers and modeled a lot of his teaching on him. I learned so much from his slide lectures and remember how he paired Vermeer with Mondrian and Morandi with Guston. He taught us how your eye travels through a painting and the important concept that a diagonal can lead you into the space of the image and also be on the surface.

Jim Weeks was part of the Bay Area Figurative Movement and introduced us to Diebenkorn, Olivera and Bischoff. That was a breath of fresh air from the old masters the other teachers were talking about.

D’Arista taught us about the Golden Triangle and how to use the proportions of the paintings in our composition. He would come into class with a bagful of objects and set up the most interesting still lifes. We could only paint with black and Venetian red and no curves- only verticals, horizontals and forty-five degree diagonals.

LG: Your paintings often switch back and forth from sharply defined imagery to work that is abstracted and loose; colorful configurations but still recognizable shapes. Does your painting’s tightness or looseness evolve on its own terms or do you start by being in a certain mood, which encourages a particular direction – and go from there?

PS: The tightness and looseness evolves as the painting progresses. I would say that instead of a work evolving because of my being in a certain mood, it’s more about color and spatial relationships. It takes me at least a week or two to set up a composition. I begin with a drawing, which for the last five years, has been on Mylar. Working with a combination of charcoal and conte crayon, I get beautiful blacks and the erased areas looks bright because of the Mylar’s translucency. The drawing is “tighter” than the painting will be but serves as a useful guide while I work on the painting.

There are many versions of the composition before the painting is done. I know I’m not alone in struggling with knowing when a painting is finished. I also know that as I get closer to finishing it I care less about resolving everything. That would explain why some areas are clearly defined and other areas are looser. When some time has passed from when I’ve finished a painting, I find I really like the loose and unfinished sections but know they only work because I’m clear about the spatial relationships

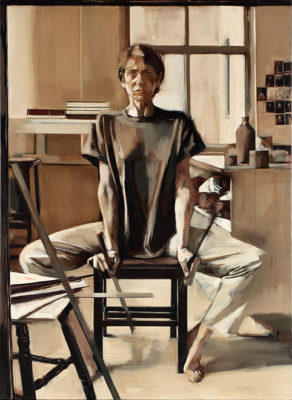

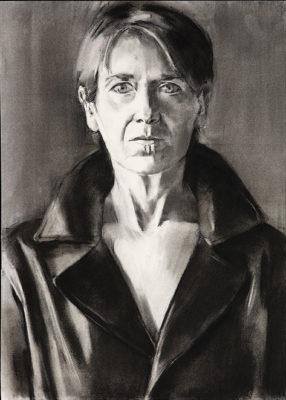

LG: Your engagement with the colored liquids on a reflective glass table subject-matter, as well as your self-portraits have lasted many years.

I’m curious to hear what you might be able to say about the merits and risks of working thematically like this for so many years?

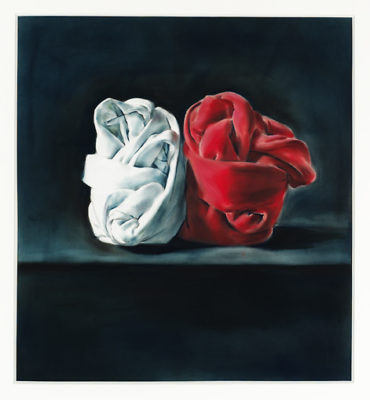

PS: You mentioned that my self-portraits lasted many years. I don’t think you know about the group of pastels I did in 1989-90. It’s relevant because it only lasted two years and is not something I want to go back to. To take a break from the self-portraits I was working on, I started drawing my son’s wooden blocks. After I tired of their hardness I picked up a sweatshirt and wrapped the blocks. I had worn sweatshirts in many of my self-portraits and loved the way the fabric could be molded. The idea of wrapping objects in sweatshirts developed to the point that I was making complex sculptures and then drawing them. Unlike the self-portraits or the Studio paintings, after two years I had exhausted the subject. The Studio paintings, which I have been working on for almost twenty years, feel open ended. When I compare the earlier ones to my new ones, I’m surprised at how different they are. It’s obviously the same physical space but the color and scale of things has changed

LG: When I was in school I remember hearing people say that galleries prefer artists that have coherent and consistent body of work that is uniquely identifiable. However, I also heard artists say having a signature style is something to be wary of – that is might risk looking too commercially driven and could stifle authenticity. How would you weigh in on this issue?

PS: I think style is something that has to be earned. I know in my own work before I make a mark either with charcoal or paint, I’m confident at the time that it is right. The next day it no longer seems right and I will replace it with something else. The scraping or wiping out of an area and the repainting it might translate as a style. Color relationships also play into what you might call a style. Is the way Bonnard used color his style? It seems to me that if you like an artist’s work, you like their style and the two things are intertwined.

LG: What, if anything, does your artwork have to do with music? Do you think of your paintings as being in certain key or using musical components as harmony, rhythm, intervals, timbre, syncopation, etc. Do you listen to music while you paint? What do listen to?

PS: Listening to classical music, especially chamber music, has always been important. Aside from listening to it while I work, I go to concerts and lectures about music frequently. At the lectures (given by Bruce Adolphe for the Chamber Music Society at Lincoln Center) a movement of chamber music is broken down. An example would be a Beethoven string quartet and Bruce would point out how Beethoven goes from dissonance to harmony. He might also point out how the opening theme is “simple” and show how he expands it as the movement develops. I become more conscious of the journey Beethoven takes you on when he returns to the theme at the end of the movement. I think this brings me back to your question about formalism. In classical music there is a defined structure – three or four movements, each with its introduction, development and resolution. Beethoven keeps the structure but breaks the rules. It’s exciting for me to see the parallels in painting.

LG: It’s often hard to focus on painting when the world seems to be coming apart. Information and imagery overload from social media and the like is a constant distraction. What helps to put this all into perspective? What keeps painting relevant for you?

PS: You’re so right about the world coming apart. I listen to a lot of podcasts, keep up with the news and am constantly depressed about what is going on. Going to my studio everyday is what I do. I believe in the tradition of painting and without sounding corny want to keep it alive.

Great work, great interview. Thanks to both of you.

Thanks Matt.

Enjoyed the interview and commentary. Love her use of color and space and the reflection of light.