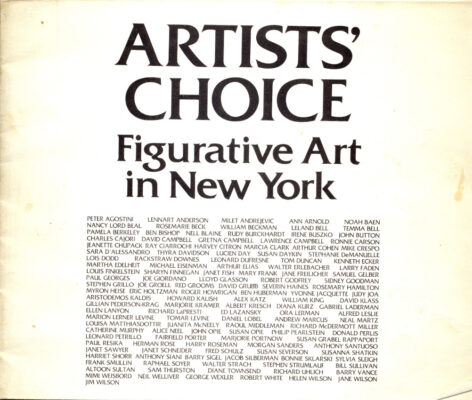

I’m pleased to present this email interview with the Long Island based painter Bruce Lieberman who has been painted landscapes, figure compositions, still life and more since the 1970’s. He recently had paintings showing in work in the group show, “MASTERWORKS OF AMERICAN LANDSCAPE PAINTING” at the Center for Figurative Painting in New York where Lieberman exhibited along with an incredible array of stellar artists such as Lois Dodd, Lennart Anderson, Paul Georges, Wolf Kahn, Louisa Matthíasdóttir, Neil Welliver and many more. Bruce Lieberman, in his early days as a painter, participated in many of the Figurative Painter’s Alliance meetings in NYC where the leading figurative painters gathered for boisterous discourse on a wide range and often heated art topics. I thank Lieberman for sharing his memories and thoughts about this and for his comprehensive discussion about his background, process and thoughts on artmaking. Bruce Lieberman is represented by Gallery North in Setauket on Long Island and Ross Contemporary, Chicago

Artist’s Bio:

Bruce Lieberman was born in 1958 in Brooklyn, New York and in the late 70’s and early 80’s he studied with the Mel Pekarsky and the sculptor Robert White at Stony Brook University. Robert (Bobby) White introduced him to Paul Georges and in turn the figurative art world and the Figurative Artist Alliance. Lieberman went on to study at Brandeis with Georges and received an MFA from Brooklyn College in 1983 studying with Lennart Anderson.

His first one-man show was at Pene Du Bois Gallery on the Lower East Side in 1982. He exhibited with A.M. Sachs Gallery and was represented by Gotham Fine Art until a major theft caused the gallery to close in 1988. At that time a landscape painting was included in the book, 20th century Long Island Landscape Painting, by Ronald G. Pisano and subsequently Bruce became associated with the Long Island landscape tradition and movement.

Bruce Lieberman’s work is in numerous museum and private collections worldwide. His paintings have been exhibited in many galleries and museums in New York and on Long Island. Critical review and commentary have appeared in books, newspapers, journals and magazines, including: The New York Times, Newsday, Huffington Post, and El Diario for example. For several decades he has given workshops, lectured and taught. Currently his work is on exhibit as part of the collection at the Center for Figurative Painting, New York.

Since 1993 Lieberman’s studio has been full time, on the eastern end of Long Island where he resides in Water Mill with his wife and two dogs.

Excerpt from a catalog essay by Jennifer Samet:

“Bruce Lieberman doesn’t shy away from “no-nos” imposed by the contemporary art world. He paints flowers, butts, and leftover Chinese food. He has a sense of humor that rings loudly in his painting, like when he punctuates a scene of blooming zinnias with a “birdy” rather than a real bird (a slightly askew garden stake), or a lumpy, awkward piggy bank in the middle of a breakfast table still life. He knows the rules and he also knows that life is short. His is a land of plenty — not shallow materialism — but of the sensual pleasures of tamed nature, sun, sea, and flesh.

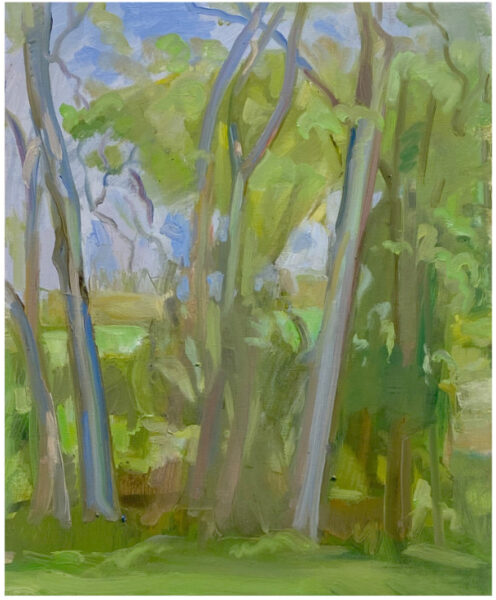

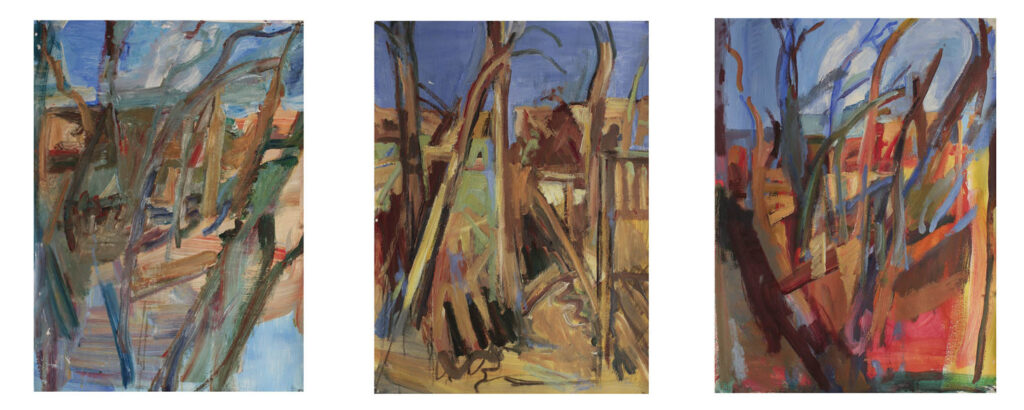

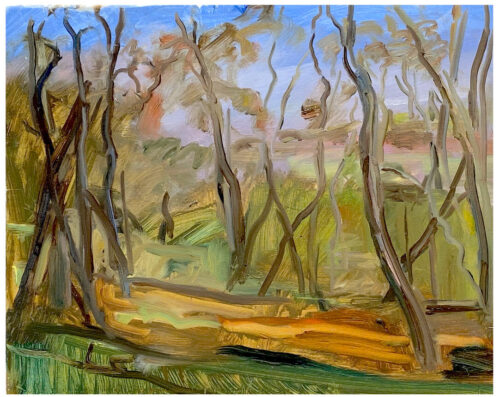

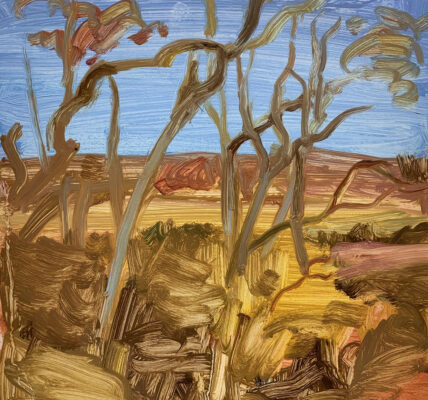

Lieberman almost never paints one tree – he paints the thicket. These repeating vertical forms, (relatively) bare in his winter paintings, become a kind of drumbeat for this recent body of work. The insistence on serial, repeated forms make it hard not to think of Minimalism, even though Lieberman’s work couldn’t be more antithetical to this aesthetic movement. While the Minimalist artists used seriality to articulate space, commercial manufacture, and an impersonal objecthood, Lieberman is determined to show the artist’s hand, the painterly gesture, and the effects of natural phenomenon — sunlight and air — on these forms.”

Larry Groff: In your talks and interviews, you talked about studying with Paul Georges at Brandeis University as a special student. Later, you studied with Lennart Anderson in the Brooklyn College’s MFA program.

I’m curious to hear how the ways Paul Georges and Lennart Anderson approached teaching and painting played out for you as a young student. I see their styles as being quite different, even contradictory at times, with Georges’ monumental large-scale paintings, sometimes with confrontational subject matter, he painted with bold flatter, higher chroma, and value contrasts vs. the more gentile, intimate, naturalistic, and harmonious close-toned and soft atmospheric edges of Lennart Anderson.

Bruce Lieberman: I was aware of, but not focusing on, any of those contradictions. To Paul, every problem had a formal solution. There might be many solutions, many roads, and it was always about color. He was loud, big, bold, fun, and seemed freer and looser than Lennart. I saw Lennart as free and loose in his own way, albeit slower and more deliberate. They both shared a concern for capturing what you perceive in the real world. But Lennart dug deeper. With Georges, it was composition and structure.

In the late 70’s, I studied with Robert White, the sculptor, who felt he had given me all he could, so he introduced me to his old friend Paul Georges. So, when I went to Georges’ studio for the first time, my girlfriend and my mother had nagged me to put my work into one of those big black portfolios and put on my little blue sports jacket. I was digging clams and farming oysters then, and it was an understatement to say I felt awkward. Paul looked at my work and my sports jacket and said I looked like a dentist. He said, “Frankly, I don’t see what Bobby White sees in you, but I don’t take a recommendation from Bobby lightly.” So, we confessed to him the mom/girlfriend story. Paul said if we go with him to the Alliance the next day, we can talk more; if not, Not. So, we went. That was his style.

Paul, much later, pushed me to get an MFA with Lennart. I went to Brooklyn only for Lennart. I already knew him from the Alliance and openings. And I was already showing in NY and arrogant, which was a byproduct of the Alliance and Georges. Still, anything Lennart said was gospel. While at Brooklyn, I did find Bob Henry, who, like Paul, was a Hoffmann student. He was tough and fantastic. A great painter married to another painter, Salina Trieff, whose work I adored.

Paul was hypercritical of other artists but had this deep and great respect for Lennart. Because of Georges’ praise, Lennart was now godlike in my book and had magical powers. So, I paid attention. That said, the Georges’ stuff was already in my blood by this time. But I was committed to this whole thing being a marriage of sorts.

Lennart always amused himself by calling me, “A Georges’ Guy.” Back then, I was sort of enamored with expressionism. From over his glasses, Lennart looked and lowered his voice. He said that he, too, started out as, or once was, sort of an expressionist. He had found it too lazy and too easy. Deep down, I must have agreed, and I threw it off.

LG: How did you reconcile these differences in style and teaching methods, and how that helped form you into the painter you are today?

Bruce Lieberman: I was looking for a way to understand my painting and improve as a painter. I was a blank slate when I met Paul, so I embraced everything. We had a lot in common, so it was easy. He spoke of composition in a way I had never heard before, relating it always to how Titian, Bruegel, or De Kooning for example, constructed and organized work. It was about the surface structure and the unity. Or simply, how did or how would Rembrandt, for example, handle this or that particular problem?

His work method was approachable to me, and how he taught these things appealed to my nature. Just dive in and take off on a big wave. With both guys, there was no pussy footing around. No schooly exercises. There it is, and paint it.

What was similar and different about them? Everything and nothing. Georges was like Gandalf taking you along on a journey, and Lennart was the sage on the mountain who slowly imparted knowledge. But the differences between Lennart and Paul were more minor than the similarities. I chose to see it that way. I married it all by finding the similarities and allowing the differences to become semantics to me. Color vs. Tone is just words. I chose to see no argument with the men’s ideas. Just possibilities and different personalities. It was about the conversation of elements that make a painting. They were all things to use- all just aspects. What each guy believed, in my estimate, was that each color, whether dark, light, cool, warm, saturated or not, has a personality that perhaps did or didn’t get along with its neighbors. If you understand the characteristics and possibilities of that color- the words; value, hue, and saturation…, become just words. The variety of color and the sensations they offer, as they relate to the other colors and shapes on the surface, is the issue. How you use and when you use the darn things. A darker red, less saturated, cooler, or warmer red, is still just a color. It is just different and holds a different power and place in space or creates a different response/reaction to another shape or area of color. That’s how I married the ideas. Their ideas.

In the end, I found it was all the same. It was the dance that they both loved, not the differences of the ideas. Lennart said he could only teach me to be more like him. Georges was the same but more open to what others might do. It was all about PAINTING, after all. It was the similarities that you could glean. If Lennart was about tone, then my, Georges’ trained, brain just interpreted those tones as different colors. There is no actual conflict there. I use black as a color to make a color, not to darken a color. The darkening was just a byproduct of creating a new color.

For Paul, one structures a painting in terms of color and shapes. Color does not mean just pure saturated color. Every aspect and characteristic of that color is – a different color. So, what is important are the masses of color and where in space they appear to exist, how they hold or yield power, move your eye across the surface and back and forth between the planes. Flat pieces of COLOR moving in space but yet on the surface. Soft edge, or hard edge, who cares, but all conceived of as flat.

In some fashion, they both were speaking about this, Paul and Lennart. But mostly, it was Paul. But they spoke the same language, albeit with an accent. It is a language of seeing and how one is perceiving the real world. Lennart may throw the word tone or value around more often, maybe into every one of his sentences.

Lennart Anderson’s teaching style:

The gems that Lennart left me were two most important things: Paintings emerge from a fog and are about the similarities and the differences.

More than anyone, Lennart gave me a steady diet of trying to get the observation stuff – the color, for example- spot on and really upped my ability to work from observation. Nail stuff down solid. Lennart pushed me to see the similarities and differences between things. Which helped everything. He found the holes in how I worked. It was my habit to exaggerate color, allow paint to build up on the horizon’s edge, and let paint accumulate everywhere, creating some annoying texture that interfered with the narrative. I never used a palette knife to scrape it all down despite his suggestion. I did not even own a palette knife and wouldn’t get one. I can still see him slapping his forehead in disgust, comically gesturing to the heavens while shaking his head and proclaiming, to no one in particular, that it’s not his fault…. “A Georges’ guy.” A friendly version of Seinfeld and Newman.

To illustrate the gospel of the similar and different, let me talk about:The Raisins.

Lennart said my work was covered with them. They were the key to my understanding of everything Lennart. I jumped way down in tone, hitting a serious dark way too fast. He showed me how to find the tones between the ones I had. Those differences of tone I did not even know existed. And it was the same for the highlight. He would, by catching the light on the ferrule of the brush, establish a benchmark for the WHITE. The whitest thing on the painting- blank canvas. Holding that sparkle up and comparing it to (seeing the similarities and differences) what you thought was white, only to find that white is not what you really see. White is never white. You might find that the white is really way down in tone and actually has a touch of something…blueish, reddish or greenish to it. Thrilling. Holy crap, I was seeing the differences. Color, browns, whites the darks I would never think about or see the same. (But I still like to exaggerate the color.. Georges, I guess.)

Weirdly I saw Lennart speaking the same language headed to the same place but just taking a direct route. Obviously, their work is very different. But they both produce these serious things from deep inside themselves. Painting was not only about being observant of the subtle relationships, differences and similarities. But embracing them so they, the relationships and forms, emerge from a similar fog of tone or color.

The “Emerge from a Fog” idea seems self-explanatory, but it was the other important Lennart-ism I took away. The FOG idea of Lennart’s is everything to me but I say that about Hoffmann too. Perhaps I married those ideas. SEE those Lennart differences and similarities in the fog, then organize and structure it through Paul.

I translated Lennart’s fog as the ambiguity- the similarities of color or tone I saw in a puddle and mush of paint that only suggested form (and the color) you pull from the swamp. Lennart told me to first draw free and loose on the canvas and not be “married” to the bad drawing. One you did for the painting in only 20 minutes and then stupidly be a slave to it- just fill in the colors? Let the thing evolve and grow through the life of the painting- emerge from the fog. Without going into detail, it was also how Georges worked as well. Sort of.

Paul Georges’s teaching style:

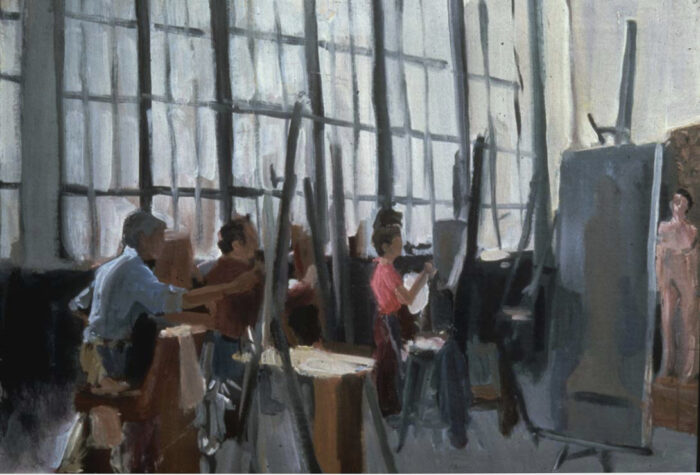

Georges took you into his world. I studied informally with him for several years and then went to Brandies for a more formal dose. We spent time at his studio with his wife and family. Went to openings, parties, shows, drew, drank, and even gathered oysters. All the time while he held court and preached Art…. Art was our religion. I became a regular at his Monday night drawing sessions, the Alliance and often tailed along on his various group studio visits and critiques. All were very casual and informal. He would do these great studio visits where we drank wine, and he critiqued work. Once a week? Once a month? He would carry a big heavy bag of art books and rifle through them to show us how something was painted, how it was flat, a pictorial device, how to organize the surface and deny perspective.

Deconstructing how Manet painted an object, and he and Goya played with space. They ignored what was accepted as correct to maintain the integrity of the picture plane; the Dead Christ of Mantegna, Goya’s 3rd of May, and Manet’s The Dead Toreador were all his examples. You do what is needed to be done, and when it is needed, throw rules away (foreshortening in this case Giotto, Piero, Bruegel, Titian – Everyone….. The whole history of Art was his examples and furthered our sense that we were in this noble tradition- and part of it- a continuum through history. Part of this proud lineage that went to the Greeks.

Georges quoted/referred to and, I suspect, mostly synthesized Hoffmann’s teachings all the time- It was everything. It was Hoffmann, Leger, and Paul himself as part of history. He dragged us back, or rather, history up to meet us. It was our guide and mentor. No giant was left sleeping, and their place in Olympus was ours to aspire to. Paul taught that history revealed a common thread of how one organizes a painting. How their paintings–all were constructed and composed–how color was controlled and used, and how utterly flat it all was. The formal aspects that they all shared.

Georges was about flat color and how everything about painting is FLAT! That became the mantra. One of many. “Paint it flat.” Think about it as flat; see it as flat. Conceive forms as flat. Flat color shapes. Georges allowed me to let things happen and embrace the mistakes, the humanness, the drips, and the accidents. Then think – step back and think about your painting and the structure. Feel free to alter and change at will. Destroy at will. Paul was in the front row of a wild boxing match. Lennart was a sunny day of baseball, quieter and more deliberate.

I was recently reminded about the Paul “see-saw.” Paul, looking at a painting of mine that was a real dog. Said to me, “Cousin, symmetry is BORING! Asymmetry is balance, too.” It is like having a big blue shape balanced by a tiny little blue shape because it sits just in the right spot on the see-saw(painting) or is super powerful. The shape’s or color’s strength will also bring it forward—Hofmann’s playbook.

Regarding tone, Paul ranted about tone or, rather, modeling. How TV and photography poisoned us to think about things in terms of black and white- as tone and detail. You had to develop the ability to see and think about the abstraction- the flatness of things. The color and shapes dancing, moving the planes, creating space, and denying it. (Hoffmann) Ways to destroy the horizon line and still allude to a place in space. Setting the planes free. That was Georges in formal terms. A new additional mantra would pop up through the years. ‘Don’t be self-conscious,” “Big shape up,” and “down in back” or “down to go back.” These come to mind. I heard it from him whether we were visiting a studio, drawing, digging oysters, or drinking wine, at the jet games, wandering museums… and it was all wonderful…all great. All ideas would be illustrated by referencing one of the great masters or a particular painting.

He seemed a master of finding the underlying systems in paintings – interesting repetitive systems or devices that held the construction of the painting together. Unified the structure of the thing- the surface. It felt like we were sitting in the park with Socrates. Walking thru the big Matisse show at the MOMA with Don Perlis and Paul, he was telling us about the space and the devices Matisse used. It was about how Matisse was making space… The foreground was always above something that dropped you back into the painting. (Bruegel Hunters in the Snow, Fall of Icarus)

LG: In what ways might the emotional resonance found in the visual and non-objective aspects of abstraction translate to landscape painting? Is there a connection between how abstract art can evoke emotion and how landscapes can connect with viewers on a deeper level?

Bruce Lieberman:

These days, the landscape dominates my subject matter. I’m in there, hiding from life, but they’re often just a foil for making paintings and playing formal games. My work is inherently personal and emotional, and that shows up in my paint handling. A bold gestural stroke is expressive and emotion-laden by nature. Making no attempt to hide the marks, the human touch, they are in many ways more relatable because of their humanity. My presence is in your face, full of energy and vitality; inviting a shared human experience. Additionally, if the surface or planes in the painting are alive and dancing, they create a dynamic visual tempo. A musical jazz of rhythmic tensions- a textural richness evoking melody.

LG:

The late Wolf Kahn, whose work is also in the “Masterworks of American Post-War Landscape Painting” show you’re in, made studio landscapes of forests and farmlands that explored color harmony and drawing that merged aspects of realism with aspects of abstract expressionism. What might be some thoughts you have about his work? How do your paintings differ or share similar concerns with his paintings?

Bruce Lieberman:

I ‘ve always had a lot of respect for Wolf Kahn and his work. There is a shorthand to Wolf’s drawings, an economy that we shared. The abstraction in his work can be incredibly powerful and beautiful. More powerful than mine. He is the real deal. That said, I don’t see him as having any real influence on what I do. Ultimately, what the hell, we are all on the same team, all in the same struggle, and there is nothing easy about it. I remember meeting him a zillion years ago with Georges, and we all went to some downtown Greek restaurant. I last saw him at Lennart’s memorial, where I had a chance to tell him how much respect I had for him and his work. I was surprised by how touched he was, and I get choked up just thinking about it.

I don’t recall for sure, but I would venture to guess those Wolf studio landscapes were started on-site or at least from studies done in the field. If that is the case, I share that with Wolf—first, working outdoors and from direct observation, and then completing them in my studio. Only returning to nature if I’m lost and everything goes south on me. To avoid further frustration, I often note the date, time of day and atmospheric conditions on the back of the canvas.

So, if, after total frustration, I have to return to the crazy thing the following year I have a starting point. That said, once back in my studio, the work begins. Everything might change. Rhythms, relationships, and accidents are developed or exploited and anything might be thrown out the window.

Recently, my work has taken on a nostalgic tone, a post-COVID reevaluation thing. I’ve been grappling with a batch of small, unfinished paintings, that had accumulated over the last three or four years. Meditative things I just could not finish. Trying to imbue them with a sense of poetry and an ethereal quality, I decided to attack them- once and for all.

Health issues have forced me to paint these without solvents, leading me to a drier technique including scraping with a palette knife, à la Lennart. Something he never could get me to do. Jokingly, I refer to this group as my “Corot/Lennart-y” paintings. Although more, often than not, I was really thinking of, a sort of “The two roads diverged… lost in a dark wood…,” type of thing. (Frost and Dante)

That said, while I was working on these I did think of Lennart. He would occasionally show up unannounced and try to mess with certain passages in my painting. Sometimes, finding it a peaceful and amusing intrusion, I allowed him in.

LG:

You’ve said in the past that you wished you could have studied with Hans Hofmann. Have you read Tina Dickey’s 2011 book, “Color Creates Light: Studies with Hans Hofmann”? https://www.amazon.com/Color-Creates-Light-Studies-Hofmann/dp/0986651109 This book goes into great depth about his teachings and thoughts on color and light, an excellent read for any painter.

Bruce Lieberman:

I haven’t read Tina Dickey’s 2011 book, “Color Creates Light: Studies with Hans Hofmann.”

I did want to study with Hofmann, but alas, he was dead. So, it was a problem. However, Hofmann students were everywhere; all over the art magazines and exhibiting in galleries and museums. Early on, Robert (Bobby) White had a beautiful show of his terracottas at Graham Modern with Robert De Niro. I was floored -transported to heaven by those paintings. De Niro and De Kooning were my heroes, so that was that. I sought out Hofmann’s students. Hofmann is still in my head today, albeit through Paul.

Georges hosted a drawing group every Monday in New York and relocated to the Hamptons in the summers. Many Hofmann students regularly attended, including Jane Freilicher and sometimes Mercedes Matter. I loved and absorbed every word.

LG:

Hofmann wanted to respect the flatness of the 2D picture plane and not use traditional perspective and such to give the illusion of spatial recession; instead advocated the often cited “push and pull” of colors, where the degree of color contrast, chroma, and temperature create a sense of depth.

Does this concept have any relevance to your work?

Bruce Lieberman:

Hofmann is very relevant to my work. It is about composition, the whole unified surface. In some ways, it is everything I do. The way color works its way “all over” the surface- from side to side, back to front, and top to bottom, creates a sense of tension and movement. It’s about weaving color and space, utilizing color and its characteristics to establish depth and spatial organization— unity and tension on that flat surface. Playing games with space by destroying and denying it. “Making and breaking space,” as Paul would say. It’s about the way color spreads ‘all over’ the surface—from side to side, back to front, and top to bottom, creating a sense of tension and movement. It’s about weaving color

LG:

Can you give more specific examples?

Bruce Lieberman:

In a nutshell, your eye might first be drawn to a specific color or area of a painting, such as vibrant red. It blares like a beautiful trumpet solo, demanding your full attention, until another color takes command of the stage. As its power fades and yields the floor, your eye is drawn to yet another color or area which now steals the spotlight. In this way, the composition remains in constant motion, rocking and rolling- as your eye is forced, from color to color in and around the surface.

This blue could represent a sky shape nestled between tree branches. If it is made to change in tone, temperature, or intensity, the result is that it would occupy different spatial planes, adding a sense of dynamic movement to the composition. It’s sort of a Cubist/Mondrian-type vibration that allows planes of color to dance rather than remain static, contributing a musical rhythm to the painting’s surface. The sky shape occupies a contradictory space, both advancing and sitting back simultaneously. Particularly in relation to the other bluesky shapes. Ah-ha! Surface tension at its best!

I hope all of this makes sense. I remember Paul Georges discussing some genius idea of his, something like, “Down in back or big shape up.” I asked him, “Why don’t you write this stuff down?” He laughed and responded, “If I write it down, it won’t be true.” I get that, but then again, I would.

LG:

Your artist statement talked about your work as a ‘battle, dance, or a collision of accidents’ in which you compose, exploit and contort relationships. This is a great summation of the painterly approach. Could you delve deeper into what this process feels like for you? How do you navigate the interplay between intention and accident, control and chaos?

Bruce Lieberman:

I just allow the shit to happen and exploit it when it does. Evaluate, assess, and re-assess, trying to be fearless about the whole thing while simultaneously beating myself up. I have to remind myself that it always sorts itself out somehow and in some way. There is always a solution; a formal issue like the color that will navigate my ass out of this chaos.

When you do it enough, it just happens, and when it does, you are ready for it, prepared to react to the unexpected and use it.

My process is about riding this chaos. Beginning in a mess and trying to wrestle something out of it. I start with a very loose free charcoal drawing, sometimes redrawing over it with ink. On occasion I will mess it up even more with a thin mix of acrylics and gesso, offer more opportunities and “fog” to navigate through. There are no tricks. Having a somewhat romantic attachment to Action Painting, my whole process is active and rather athletic. That alone lends itself to an expressive emotionally charged paint. Allowing for accident and mistakes that offer endless possibilities as well as troubles. I work wet into wet, fast and gestural although a painting takes months or years to complete itself. On a good day I’m just along for the ride.

So, how do I navigate the interplay between intention and accident, control and chaos?

Thoughtlessly and thoughtfully. You to leave yourself and hit that zone. Lose yourself in between some intelligent decisions. I am prolific- to a fault perhaps. I have come to see the process as a chance to embrace being human and the marks and accidents as footprints of the journey- the human experience. What it is for me to be a painter. I’m just not neat, clean or slick even if I wanted to be. I try to fill my world, the picture plane, with intelligent decisions. Try! It is a metaphor for life – life is chaos! Mine sure can be, and mostly I feel like I’m just swept along for the ride. But things happen in sometimes tragic ways. Same in painting to some extent. Certainly, life can be very peaceful and contemplative, but very often it is about juggling all of the moments. We are all just trying to keep our heads above water and make it back to shore and not wipe out on the reef. Thru, all that thrashing around, juggling the stuff, and the chaos, we try to remember to enjoy the ride. Seems like painting to me.

Pandemic life confined me to my property, so I turned it into a palette full of motifs. I don’t do preliminary drawings/sketches much anymore, thanks to a hand injury. Instead, I use small paintings as studies for larger ones, revisiting subjects to really get what they’re about.

How to PAINT it. I work on paintings for years and years. Lennart and I used to joke about how this happens…since sometimes I could/ would finish a painting in about 3 hours. I got the feeling he related and spoke from experience, if it fell flat, he laughed, it would now take, not the 3 hours, but 3 days, 3 weeks, 3 months or 3 years.

LG:

Please tell us something about your paintings in the amazing show at the Center for Figurative Painting in NYC , “Masterworks of American Post-War Landscape Painting” exhibition(July 11-Dec 28, 2023). The show has many luminary painters such as Lennart Anderson, Rosemarie Beck, Jane Freilicher, Paul Georges, Wolf Kahn, Aristodimos Kaldis, Albert Kresch, Gabriel Laderman, Louisa Matthíasdóttir, Philip Pearlstein, Fairfield Porter, Seymour Remenick, Paul Resika, Neil Welliver. Many of these painters, including yourself, were active to some degree in the Figurative Artist Alliance that was active in the 70’s, is that part of how the work was selected?

Bruce Lieberman:

I’m told the connection I had with some of the folks in the show and the Alliance, had to do with my paintings being selected for this show. At the Alliance, I was just another young painter sharing in the experience. A few years ago, after CFP saw my work in an exhibition at the Nassau County Museum of Art, several of my new paintings were purchased for the collection. So, now my work is hanging in a show with my heroes and friends. Of course, I’m loving that.

The paintings in the Center’s collection were part of a group I jokingly refer to as my “Covid Driveway Paintings.” In October of 2019, I caught something from my students who had recently returned ill from China. After 5 sleepless nights gasping for air, I went to the hospital. So, my pandemic experience was rather serious. At that time, no one heard of COVID. Eventually, I was told I had lung disease resulting probably from years of turpentine and damar use. Had to go solvent-free and subsequently shorter and drier paint rather than the very wet and drippy stuff I was used to.

Come spring, I was setting up my easel at the edge of my driveway incredibly amused by the idea I was stopped by some imaginary force field. Working at the furthest edge of my property I painted in every direction but still afraid to leave.

LG:

Can you tell us more about what it was like being a part of the Figurative Alliance back then?

Bruce Lieberman:

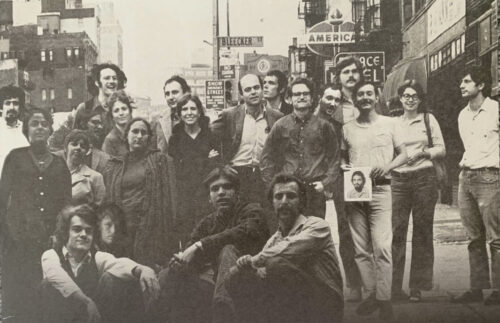

As a very young painter the late 70’s/early 80’s the Alliance was – thrilling. Being there felt like I was living a version of the old Cedar bar days -an embodiment of that Abstract Expressionist spirit. There were serious conversations by serious painters- men and women who were dedicated and very passionate about painting. Often fiery, wild, and wonderful, the Alliance was full of regular working stiffs. Someone described it as a “Wild West bar room.” Sounds right, but it was also a Scorsese Lower East Side New York mob movie set mixed with a bit of the Star Wars bar.

I first went to the Alliance the day after I met Paul. As per his suggestion, I drove him and his wife, Lizzette, over from his Walker Street studio. As he got into my car, he said,” it is a good thing that you came tonight. Cousin.” Which meant I was in, and I was The Cousin from that day forward.

The Alliance had its share of cantankerous souls and emotionally heated debates that were all typically punctuated by loud, chaotic, angry yelling, laughing, and jeering. Nobody was going defer, or be deferential, to the anyone. The crowd suffered no fools. There was also a surplus of bigger than life personalities. Paul Georges being one of these.

That first night they had four very heavy speakers. Hilton Kramer, Irving Sandler and two others, who I just can’t recall. I also don’t recall ever seeing the place that crowded again. Wall to wall artists, standing room only. Full of real painters. Alex Katz was standing a few folks down from me, Pearlstein, Rackstraw, Lennart everyone listening to these big cheeses talking. It was a very cool experience for a 19/20-year-old kid. That evening it was shockingly loud, and the crowd was ruder and perhaps more than characteristically, tumultuous than I would ever see again. There was no shortage of noise and taunts from an audience who were all fighting for a turn to hurl comments at the panel. Then Georges stood up and the room went silent. My girlfriend, now wife, dug her nails into my arm. We were in shock. We did not know anything about Paul. Just that he was a Bobby White’s friend, real painter, with a real studio, and a Hofmann student. Seeing him command such respect, I was sold.

From my stupid kid perspective, it was amusing to view the scene at the Alliance like a high-school cafeteria with its distinct cliques. I’m sure these folks didn’t think of themselves part of any group, they were all just friends and fellow painters. But each group seemed to have a unique style, which I thought of as, “a smell” to their work. The Brooklyn guys all had these domestic street operas, Life on the Stoop; in retrospect maybe they were really a Queens Laderman group? Or maybe Lennart’s old students? Among others, there were also the Leland folks, our Georges wedding party and the others- I referred to as the ‘side guys.’ One such group was seemed centered around Peter Heinemann, who had a reputation for being tough and street-wise looking for a brawl. They scared the heck out of me. The myth was that he, an ex-golden glove boxer, after a few drinks liked to punch people out. I stayed clear but one day after a Bowery opening, sitting at the bar in Fanelli’s Peter sat down. Over several drinks we talked about life and art. He was a wonderful artist and a nice man.

I read a characterization of Paul that I found surprising. I was blessed to tag along with Georges and his friends, a group of artists deeply, even obsessively, engaged with ideas. This wasn’t a group of “henchmen,” but a community of serious artists grappling with issues of significance. After the Alliance meetings, a group of us would migrate to Mare Chiaro, a bar in Little Italy, where our discussions would continue but now perhaps somewhat alcohol-fueled. Conversations were deep and thoughtful, revolving around the act of painting, and maybe seasoned with a bit of gossip. I might have learned more about painting at these places than anywhere else.

LG:

Lately, I’ve tried to guess what percentage of the people at art receptions are over 60 or so. Art shows that feature painterly abstract or representational paintings seem to attract grey hairs more than green hairs.

Do you think that there is waning interest from younger people for the formal, visual concerns that our generation held dear? If this holds true, what do you suspect the future of painting will be like? I think fewer folks care about what I consider pure honest painting. Painting base on perception and some version abstraction that implies to a consideration of surface and materials.

Bruce Lieberman:

Maybe we go to the wrong openings? I’m not too optimistic. For years I’ve trained students in some form of traditional painting and drawing, only to see them diverted toward more conceptual programs. I saw good painting students, after leaving me, making installations maybe just to please the rest of the faculty. I have a few ex-students, who stayed with it. Perhaps most did not see the depth that is required to make work that is both personal and powerful. Paintings that aim for a form of poetry and demand the viewer’s participation and contemplation instead of entertainment. Instead, they often mistake honest perception for some surface depiction of reality, looking for some sort of “finished” product. Paintings that are pretty beach house sofa art or just look like they are about photography. I’m exhausted by it all. Anyone with a brush is a painter these days. Galleries resemble furniture stores but without furniture. The future? I have retreated inward. I just paint. Hopefully, the future can’t find me.

LG:

The population explosion of painters over the years has made it extremely difficult for lesser-known painters to find venues to show and sell their work. The fact that many galleries can no longer afford to stay in business compounds this problem.

When I was in art school in the 80s, there was little or no discussion about how to survive in the real world as an artist other than to get a job teaching or find someone to support you. Any thoughts on this topic you’d care to share?

Bruce Lieberman:

Beats me. I managed to survive in spite of myself. But maybe it was a good thing to not focus on how to survive. You need a day job, a rich partner, or teaching, but the adjunct thing pays nothing these days and living costs a big something. Maybe art schools should teach a trade or at least push business classes.

There might be more artists than before, but potentially there are more opportunities. The digital age has opened up a realm of possibilities that simply didn’t exist before. I’m clueless about it all. It is certainly easier than making and dealing with slides. We can all remember slides. There are also a zillion residencies and grants available. As Dave Hickey points out, in an interesting fun rant, today’s model for success is about building such a CV filled with such credentials rather than having great work.

Young artists need to be part of something- a circle of artist friends – a community. They need a support group to help them paddle thru the rough surf, make and seize opportunities. In the Hamptons, perhaps there more such opportunities than elsewhere. Here, many of my former students have carved out a niche for themselves; they’re showing and attending the right events. They are working “it.” They have style. I hope they also find substance too. For me it is always about – the PAINTINGS- not how well you can crash a party. While some may be buoyed by early success and an adoring crowd, the real challenge lies in sustaining that heat and creative momentum.

LG:

Can you tell us something about your experience in getting your work shown and making a living as an artist?

Bruce Lieberman:

Getting my work shown was a direct result of having the work- because of my work. But it was also the fact I was out there! My rule was that every ten openings, something would happen. I attended art openings regularly; I sought the company of artists who were more accomplished. They were folks who thought my work was worthy of- something. This made me work more and push myself harder.

I love that Abstract Expressionist story, true or not, that they all figured they would never make any money painting. Some purist thing I took to heart. The painters I knew, all banged nails, painted houses, or made a living teaching. They did what they had to do. And they PAINTED.

I did my day job just well enough to keep it. I dug clams, farmed oysters, banged nails, painted houses, and sometimes had three different things going at once. Then I taught. But I always painted. I would wake up at 3:30, drink a gallon of coffee, and paint before work. When I came home, I worked until dinner. Putting in ten-hour days on the weekends and during school holidays, I kept it going. Paycheck to paycheck, painting sale to painting sale, I raised my family. Well, maybe my wife deserves ALL THE credit for that.

Social commitments like attending NYC openings and Monday drawing sessions lasted until my age and physical limitations intervened. I’ve had my share of lucky breaks and setbacks—two years’ worth of narrative paintings were stolen from a New York gallery, and I spent five years paying off legal fees. No longer being in New York had its drawbacks, but I kept painting. I worked as if history was watching me. That is how I survived.

Finding the right gallery has always been a challenge for me. Finding one that believes in both you and your work is hard to come by. My approach to courting galleries is lackadaisical at best, and the results are predictably inconsistent. I’m in no hurry. Yet, over the decades, I’ve managed to show and sell my work. This business model is not for the faint of heart; it’s suitable only for both the delusional and those living on a teacher’s pension. My delusion and success lie in placing value in the process—in the making of the art itself, and earning the respect of those painters whose opinions I hold in high regard.”

LG:

Is there any specific advice you can offer young artists navigating today’s saturated art market, Or is it all hopeless, and just paint for the love of it?

Bruce Lieberman:

I lean toward the latter. I think it is all hopeless, and you should just paint. Paint because you can’t help yourself. Make the best paintings you can and then get out and network. Surround yourself with artists who are more skilled and experienced than you are. Show your work wherever and whenever possible. Find a way to make money so you can be free to paint what and how you want- and the way you want to.

If I haven’t imparted any advice yet, here it is:

Paint because you love it and need to. Paint as if history is watching. Just paint! I know it is a silly thing to say and perhaps even sillier to do, but do it anyway. Paint for history. Just strive to make the best work possible so that it might actually be worthy of that silly ‘History’ statement of mine. In my view, that is enough of an ambition. Just tend your garden. Strive to create better than mediocre paintings. Expect to fail, but just maybe, every so often, you catch some lightning in a bottle.

Good, wise painter talk. I enjoyed the descriptions of NYC and the Artists Figurative Alliance way back in the day. There was a figure drawing group also…maybe in the Green Mountain gallery… where I would flee when there was no heat in my Alphabet City tiny walk up. I enjoyed hearing about Paul Georges, who I only briefly met. No mention of Gretna Campbell, Paul Resika, Kaldis, Laderman and

Leland only briefly and other figures of that magical time long ago. But good old fashioned painter talk that I enjoyed. And mentions of the Hoffman School! What about the Studio School?

“Paint as if history is watching.” Great line, and notable in todays online, rapid fire culture.