I’m delighted to share this email interview with Beth Bernhardt who wrote from her home in France. I was fortunate to meet her a couple of times in the JSS in Civita program in Civita Castellana a few summers ago and wanted to find out more about her life as a landscape painter in France. I would like to thank Beth Bernhardt for sharing these highlights of her background and thoughts about how she goes about transforming pigment into these stunning visual celebrations of light and air.

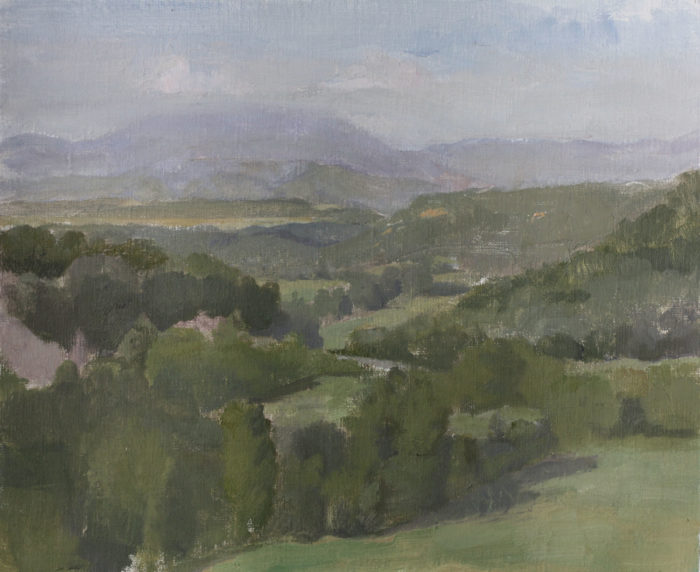

from her website…Beth Bernhardt has lived and worked in France for the past seventeen years. After earning degrees from Yale University and Boston University she moved to Jerusalem where she spent a year as artist in residence at the Jerusalem Studio School. The sharp contrasts and brilliant contours of the desert light shifted her attention to the landscape where her focus has rested ever since. She subsequently moved to France where she established her studio in Lyon for a few years before moving to Paris for a decade. Recently she settled in Nantes with her family and began painting the surrounding Loire Valley and Atlantic coast. Landscape has remained the center of her work, seeking to capture form and light and achieving a painterly description of place. She has exhibited widely, participating in various group exhibitions throughout the United States and Israel, and in France has had solo exhibitions at the Ile de Versailles in Nantes and the Nabokov Gallery in Paris. Her paintings and prints are held in various private collections worldwide.

Larry Groff: What made you decide to become a painter and what early influences were important to you?

Beth Bernhardt: There was no single event that made me decide to be a painter but a number of influences that pushed me in this direction. If I were to start at the beginning, growing up in Baltimore, I suppose I encountered my first influences at home and also at school where it was normal to talk about and look at art and where creativity was nurtured, it was normal to just make things. My mother taught elementary school art and also gave tours at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore so we went often to the BMA, the Walters and also to the National Gallery in DC to look at paintings from a very early age. I remember falling in love with the Matisse cut-outs in Washington and also as a child liking the Roy Lichtensteins, his blown-up, painted comic strips really appealed to me at this early age. In Baltimore there were Matisse’s Pink and Blue nudes in the Cone collection and a certain aura about them that made me extremely curious. As far as school went, I had always followed the art courses throughout my public school education and was extremely excited to begin painting in 10th grade. At my high school in Towson and in the Art program led by Theresa (Terrie)McDaniel, there were many students who were painting, developing interesting bodies of work, and graduating with the intention of pursuing painting as far as I could tell. The quality and sophistication of this high school program played a critical role in my decision to become a painter. It was exceptional in both the way painting was taught—we were taught to see big relationships (versus learning a technique)—and for our exposure to other painters—Terrie had a library of hundreds of art books for us to consult and take home. So you could say I got hooked on painting in high school and have been with it ever since.

To answer your question about early influences, during this period when I first started painting, I looked a lot at the Bay Area Artists including Richard Diebenkorn, David Park, and Nathan Oliveira and also a lot at Fairfield Porter. Fairfield Porter was interesting to me because of his color choices and also the subject matter that he painted—a world that was familiar to me, almost mine. These are painters that I still love and whose paintings bring me lots of joy.

LG: You studied at Yale for undergraduate degree and BU for your MFA. Were you studying with John Walker then? What was art school like for you?

BB: I knew before choosing to go to Yale as an undergrad that there was a strong art department with a long history of painting. One conversation I remember having in particular before enrolling at Yale was with then chair of the Art department, John Hull. He said that a major asset of attending Yale was the proximity of two great museums (The Yale Art Gallery and the Yale Center for British Art) and that it was an advantage to study painting at a place that had access to such a great collection. He wasn’t wrong. I did spend a lot of time in both museums and especially with Constable’s landscapes and seascapes.

When I arrived at Yale in the fall of 1993, the climate was somewhat different and the art department was in the process of transition. Nonetheless, as an undergraduate I was less directly impacted by the fluctuations of the Graduate School. During my freshman and sophomore years I studied painting and drawing with Robert Reed and Richard Ryan and during one summer worked with Bernard Chaet and Barbara Grossman at the Vermont Studio Center. We were encouraged to spend our summers at places such as the VSC because as art majors in a university setting we did not get as much studio time as students at art schools. There was a major emphasis on drawing from observation and working on a particular subject or theme in a series. If you are familiar with Bernard Chaet’s book, The Art of Drawing, much of the work I did at Yale came from Chaet’s teachings. Another teacher who had a large impact on me was Natalie Charkow. We worked in clay in her class, sculpting from the figure—we were learning how to see and the experience was invaluable. I would have loved to study painting with William Bailey or Andrew Forge but unfortunately I did not get a chance as they were no longer teaching by my Junior year.

I jumped straight into an MFA program after graduating from Yale and working with John Walker was an extremely positive experience. The graduate community was also something of a dream come true upon arriving in Boston—a positive and nurturing environment. At some early conjuncture in my first year at graduate school both John Walker and Al Leslie encouraged me to get outside to paint (I had been working on some invented landscapes in the studio). John had a place near South Dartmouth on Buzzards Bay and I would drive there from Boston and spend half of the week painting outside. Sometimes I would work on very large canvases outside that basically only fit into the back of a pickup truck. The paintings were very energetic and had some interesting passages. Working outside pushed me to synthesize things extremely quickly and nature found its way back into the work. Although I continue to work outside, my approach has evolved since this period.

LG: You later studied with Israel Hershberg at the JSS in Jerusalem why did you feel the need to go further with your training? What was that like?

BB: When I arrived in Jerusalem in February of 2000, it was thanks to a traveling grant and not entirely a decision to continue studying, although Israel Hershberg definitely opened my eyes in ways that I hadn’t foreseen. It all began out of a desire to travel after graduate school and to create a project that would give me time to paint. I was inspired by a recent trip John Moore had made to Israel and the landscape paintings that resulted from this trip. John put me in touch with Israel Hershberg and I began formulating some applications for traveling fellowships. Eventually it was Israel who came through with funding and managed to put this traveling and painting dream together. The JSS had formed a few years before my arrival and the school was located in Talpiot where students were working in a large north lit studio essentially from the model.

Upon my arrival, I assisted to a few of Israel’s classes but mostly worked from the landscape and brought my work to the school when Israel was teaching and available for critique. From these sessions I definitely got drawn into his teaching because he made sense to me in ways that six years of study at American universities can do just the opposite! He talked about hitting the right note, and about color-spots, a word that I had never heard up until that point in time and also about giving more attention to what I was mixing on the palette. My work started to shift because I became really intent on painting the light of Jerusalem and not just some random situation. I wanted people to look at the work and say, that’s Jerusalem because of the color, not because of something tangible like a recognizable building.

What are some of the biggest changes you’ve gone through with your work?

BB: I think you could qualify that year in Jerusalem as a major changing point, one when I became quite intent on describing things with more specificity. My landscapes became less concerned with the gesture, or gesture became something I was willing sacrifice in my process in order to move my paintings forward. Otherwise I have periods where I work more outside or more in the studio, but I don’t think you could qualify that as a major change. The approach has always been the same, although I do feel somewhat recently that these two ways of working are finding more common ground.

LG: You have been an artist resident in Civita Castellana, Italy as well as painting in many other locations in Italy. Please tell us something about your experience there?

BB: Painting in Civita Castellana has been a great experience for me on many levels and I have managed to go back every year since 2013. Stepping into the Italian landscape, one sees the obvious correlation with the paintings that were made there by Corot, Valenciennes, Thomas Jones and others I admire. I can’t really underscore enough the impact of such an experience. It is like coming back full circle in my relationship with these painters because it’s possible to see how their language and their mark-making are directly tied to the subject—how the the landscape led to the work…

In Civita I also connect with painters over an intense two week period in ways that don’t seem to happen here in France. I am definitely invigorated by a town that is crawling with close to one hundred painters over the summer. I find myself surrounded by painters with similar concerns and motivations and this community in turn pushes the dialogue forward, brings the conversation to a new level and helps me to stay close to my center, basically what is important to me as a painter.

LG: What painters have influenced and inspired you the most?

Being in France has given me the opportunity to look at a lot of French painting. When I lived in Paris I was at least once a week in the Louvre where I spent hours with the Corots, Poussins, and Chardins, looking and drawing. I got to copy Poussin’s Echo and Narcissus but unfortunately never got the authorization to copy Corot. I have looked a lot as well at Henri de Valenciennes and the Barbizon school that hangs in the same rooms as Corot and Valenciennes. When one is as focused on landscapes as I am, I think it is hard not to be heavily influenced by Corot, he is such a master of color and light and the organization of both. The two Corot rooms at the Louvre have a marvelous selection of his work, especially the paintings done in Italy. They are also surprisingly often empty so it’s possible to spend a lot of time with the work. You can get close to the surface, see how the paint is put down and actually see the color for what it is and not how it is reproduced in books or backlit on a screen. Looking at Corot has taught me a lot, but putting what I glean from the paintings into practice is in some respects the work of a lifetime.

One thing I loved to do as well was find the places where some of these paintings were made, mostly the french ones because that is where I live. So I went to Ville d’Avray and to Mantes la Jolie in search of Corot’s motifs. I also did the same for Balthus and his painting of Larchant. What was surprising and moving in Larchant was discovering that the church really is disproportionally large.

Some other painters on the long list of painters that inspire me are Morandi, Dickinson, Albert Marquet, Gwen John, Albert York and Courbet. I think the Courbet paintings I love the most are the ones which are just about the landscape. No figures, no objects, just light hitting a rock or a shadow slicing across a hillside. This is basically the subject matter that drives me to paint, the stuff I find exciting.

I also have been awfully inspired by Edwin Dickinson and have looked a lot at his paintings of Paris such as Paris Windows and Carrousel Bridge from 1952. He makes the Parisian pierre de taille that is quarried near the Seine glow—thinking about how he does that is definitely an inspiration to paint. When I look at Albert York I am in awe of how the paint application is so felt in connection to what he is describing.

LG: Why did you move to France? What has living there been like for you as a painter?

BB: I think there are two answers to that question, the first being that my family and more precisely my husband brought me here. I have been here for about 17 years—from the time I left Jerusalem and graduate school. However, the other truth is that I didn’t want to go back to the states at that point in time, I wanted time to develop my work beyond the gaze of my peers and outside of the circuits that I knew. I suppose I could have gone to Vermont to find that solitude and proximity to the landscape but I ended up in Lyon.

When I moved to France, the language was my initial barrier and it took a few years to be at ease in French and quite a few more to become eventually fluent. That initial distance with the world around me just really fed my studio and painting practice: at least I didn’t need to talk to anyone in french. I first settled in Lyon and began painting the landscape around me. There was a strong southern light in Lyon and I was initially drawn to the arid, sunny, and foreign landscape (it wasn’t Baltimore). I explored the surrounding countryside in an old Fiat Uno and eventually found one or two spots of predilection where I would set up my easel.

I remember actually deciding one day to take a nap in the landscape after completing a painting and waking up to vision of a man on a white stallion. I actually thought it wasn’t real, but it was—the kind of landscape experiences that became routine near Lyon. I really enjoyed painting and growing as a painter in this region. There were similarities to the landscape in Israel that created a sort of continuity for me at this stage. I later moved to Paris and one of the first things that struck me there as a painter was the light. When the sun was actually shining there was a coolness, a bluishness to the shadows and a clarity to the sky that again just made me want to paint landscape.

LG: What is the art community like where you live in France? Are there many painters painting observational landscapes? How well does the French “art world” respond to landscape painting, is it similar to what we find in the US?

BB: You might be in a better position to describe how the art world responds to landscape painting in the US. In Nantes, where I live, I haven’t found that many painters painting landscapes from observation, a handful really, and in general it is rare to see observational painting in the galleries. My experiences traveling to places like England or Spain seem to confirm that observational painting is well and thriving elsewhere, it’s just not so prevalent here .

The answers to this are rooted in the art schools and teaching professionals in this country and certain decisions that were taken on a national level going back 50 years. Until recently, you couldn’t find painting in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. One could call it a problem of transmission. In wanting to define the future they broke with methods and traditions of the past and the field of people with an intimate understanding of painting just thinned out. I have friends who have graduated from the Beaux-arts and who wanted to study painting but simply weren’t given the possibility—there wasn’t anyone teaching it.

It would be wrong to say that currently it is not happening in the schools, its just that you don’t put into practice something of quality after 50 years of non-existence or peripheral existence. A recent tour of Parisian galleries did confirm the presence of painting in a very vital way—and some very good painting—none of which I would qualify as observational stricto sensu but based on the observed world. It was one of my first gallery tours in recent memory where I could feel the ground under my feet. That being said, painting in France still feels like the exception and not the rule, the idea that to make good art you start with a concept hasn’t lost much ground.

LG: Is there a French equivalent to the popularity of the “plein air” movement seen in the US? Anything you’d like to say about it?

BB: Considering that plein air is a French word one would expect to find it here and one does to a certain extent albeit not in the same form I would say as in the US. I think in the US there is something of a commercial aspect to what is happening, a sort of look and method that stays somewhat defined and constrained by the look and method. There is also the athletic posturing that comes with it, as if the faster one of these paintings is made the better; or a tendency to brag about extreme weather conditions…These things are part of the pleasures and pains of painting outside but to turn it into a method is missing the point. So to come back to your question, there isn’t really a plein air movement here that has achieved the kind of popularity as the current American trend. It remains something a bit peripheral, that maybe some artists or serious artists are even embarrassed to admit that they do—like it is not cerebral enough. Sometimes I will get a smirk when so called art professionals discover that I actually paint outside with a “chevalet.” It’s as if one needs to choose a camp.

LG: Can you tell us something about your process, how you go about making a painting? Do you make drawings first or just dive right in?

BB: I generally start most paintings from observation or in the case of larger works, from studies made on site. I tend to make a lot of starts and save the analysis for later. I don’t think of it as a process really, more like tendencies or ways of going about things. To me, process implies order, something that is stable or immutable and sometimes that order changes for me. I think I am driven by the need to get myself to the place where painting can happen—I mean that both figuratively and literally. If that means getting outside in the landscape, then that is what I will do. The excitement is important to me. That is probably one of the reasons I am so drawn to landscape painting.

To describe this in a little more detail, I basically begin by finding a motif: something I want to paint and that wants to be painted, and I lay in some basic notations with either charcoal or a turpentine wash. I tend to draw a lot with the paint, wiping things out and selecting until I am ready to dive right in. At one point the notations will evolve into painting in a sort of seamless way usually because I will want to lay in some masses with more specificity. The painting stays open for quite a while and I won’t hesitate to change things, even my point of view can shift.

If what I am looking for happens outside, great—if it doesn’t, the surface either gets scraped down or put aside for later. Removing the paint is as important to me as putting it on and an extremely helpful way for me to move the painting forward.

Here on the west coast of France, the conditions outside can change a lot from one day to the next so I have had to find ways to continue in the studio. I know what I am going to say next might sound somewhat contradictory, but that is the way it is. Either I am able to continue in the studio with the motif still fresh in my head or I have discovered over the years that the further removed in time from the actual experience of painting outside, the better. This is because I am no longer remembering but problem solving. I have moved on to a mode where I am painting to get things to work and my memory is no longer bothering me with distractions based on a certain reality.

LG: How important is being faithful to the colors and forms you see in the landscape? What is most important to you with regard to color?

BB: To me, observational painting isn’t really about being faithful to colours but about being faithful to relationships between the colours and forms. I am always making comparisons in what I am looking at, such as how light for how dark, how warm or cool, and it is the establishment of these relationships on the canvas that guides what I mix on the palette.

That being said, I am always trying to be specific in my color. Greens in Jerusalem and Italy aren’t the same as the greens here in France and I do try to be faithful to that. Beyond that, it hard to say what is meant by faithful precisely because of the relationships. I am adjusting things in relation to how they look on the canvas next to each other and in comparison to what I am describing. When I am outside mixing color, I am really trying to mix up something that describes the light and shadow that I see and it is not really something I can pinpoint or name. In the landscape, I don’t really ask myself what is the color of a certain bridge but does what I just mixed up accurately describe the light on the bridge.

LG: How do you go about deciding what to paint?

BB: I paint what is around me, often exploring and then returning to familiar places at different times. I tend to find places, not necessarily views and these places often open up with several motifs. In choosing a motif I look at the geometry of the composition, the organization of lights and darks and how it stacks up on the canvas. I don’t make paintings that I am not excited about painting—in other words, I am drawn to what I am painting, but I definitely don’t mean that in a sentimental way. My relation to the subject is formal, I will like the shape or the color of elements in the composition and I will want to make a painting from these elements. Often I am responding to paintings that have greatly inspired me and taught me something about painting; a dialogue with other painters. This long and rich history definitely informs the choices I make and how I look to construct a painting.

LG: Your paintings are filled with a marvelous sense of light. What concerns do you have with regard to getting a feeling of light and space in your work?

BB: Well I think you could say it is a major concern and one of the qualities that I am looking for that drives the painting. If I feel there is no light in a painting I will just proceed to paint over parts of it and continue adjusting my relationships until something starts to work. That is one of the reasons that I start paintings outdoors—there are so many relationships to establish that I feel that I need to grab a few from the nature. Sometimes I succeed but often I don’t—I need to live with the painting for a while to be able to see it correctly.

In my studio I have many things going on and often some paintings that are turned to the wall. I also have a pile of starts and unresolved work. I will sometimes sort through this stack like the way one sorts through diary entries, bringing me back to a specific place or time. One will sort of scream out for attention or there will be an immediate realisation about what is not working (that is the advantage of putting things face down for a while). Sometimes it doesn’t take much but the effect is immediate—like someone turning on the lights or the sun coming out. That is the point I am trying to reach. When I find the right color note this happens.

LG: What gives you the greatest pleasure in painting and what do you need in order to get to that place?

BB: Well I think it is a continuation of what I just said “when I find the right color note, this happens.” It is this visual climax that I am aiming for, the moment when you know things are right. In order to get to that place I just need to paint, move things around, take chances, put myself in the right mindset, and be patient with the problematic ones so that the paintings reveal themselves to me.

Great interview! Thankyou. For anyone interested in the work of Corot and Courbet’s landscapes there are resources online that are worth downloading.

The National Gallery’s Technical Bulletin #30 has a substantial article “Six Paintings by Corot: Methods, Materials and Sources” – pdf available here: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/technical-bulletin/technical-bulletin-volume-30.

The Getty Virtual Library has “Courbet and the Modern Landscape” as a free ebook. http://www.getty.edu/publications/virtuallibrary/0892368365.html?qt=courbet

Another terrific interview. So glad you’ve brought Beth’s beautiful work to your devoted community of artists.

Excellent interview with extraordinary landscape painter Beth Bernhardt! Every living painter should regularly confront her work. Simply enlightening and a visual régal!

Good painter. I see the influence of Hershberg, but she is her own painter. Great command of tonal values giving the work a quiet but grand poetic force. Good for her, and good for you for exposing this talent and others who deserve it.

Beautiful work. I think Beth’s comments about the plein air scene in America are on target.

Great to read this interview. It’s a pleasure to see greens handled with such variation that they enliven the paintings without overwhelming them.

Fantastic insights into landscape painting