by Elana Hagler

David Stanger is a painter and individual of great depth and sensitivity, with a sharp, probing intellect. It has been my pleasure to get to know him and his work better through this interview, and to now share it with others who might benefit and enjoy.

Stanger grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he also currently resides. He received a BFA in painting from Syracuse University, studied painting and Renaissance art history in Florence, Italy and earned an MFA from the Hoffberger School of Painting at Maryland Institute College of Art.

Stanger moved back to Pittsburgh in 2005 and served as the Director and Curator of the American Jewish Museum until his return to teaching in 2008. He is currently an Associate Professor of Painting and Drawing at Seton Hill University.

His work is exhibited internationally at such venues as the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Carnegie Museum of Art, the Mattress Factory, the Butler Institute of American Art and the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, as well as Manifest Gallery, Seraphin Gallery, and the University of North Carolina at Asheville. Stanger’s work can be found in many private collections and is most notably in the collections of the Carnegie Museum of Art. View his website, davidstanger.com here.

Elana Hagler: Welcome, David, and thank you for agreeing to do this interview. I’m looking forward to getting to know you and your approach to painting on a deeper level.

David Stanger: First, I’d like to say thank you for your interest in my work, Elana. I have long admired your work and have been reading your and Larry’s interviews over the years. Painting Perceptions is a great resource for painters working today. It is an honor and I’m so happy to have the opportunity to share some of my thoughts and history.

EH: Did you grow up in an artistic family or is what you do professionally a real departure?

DS: My path as an artist could be seen as a departure, but I honestly can’t fully answer the question. From one perspective the answer is yes, with the exception of a distant aunt, there are no professional artists in our family. However, my story is a bit more complicated because I was adopted as an infant. My birth records are sealed and I know only that I have Italian ancestry. I have no sense if there are other artists in my genetic family tree.

Not knowing is part of my life and it colors the way I understand and translate my tangible memories. When I was younger, I sometimes had the feeling that I was living a parallel life somewhere, and I would let my mind drift. If a different family had adopted me, could I have become a different person or would my inner nature have expressed itself regardless? Perhaps there is something innate in me that drove my early desire to be an artist, or perhaps it was my familial environment that truly shaped my path – probably both.

I’m lucky to have a supportive and loving family. My mother is a voracious reader and was a librarian and social worker and my father had a long career as a psychiatrist here in the Pittsburgh region. The nature of my parents’ study and professions revolved around helping people, and this sense of social responsibility instilled in me the notion that the betterment of one’s self should to be tied to the enrichment of society. The arts do that in spades.

My parents took note of my interest in drawing and painting from a young age and enrolled me in a few classes at the Carnegie Museum, where I made my first drawings from works in the permanent collection. The art teachers in my public school were faced with an academic culture that was largely indifferent to visual arts, so I had to find my own path into painting. I set up a studio at home and figured it out as I went along. The feeling of visual discovery was intoxicating to me and I have so many good memories from these early experiments.

Eventually, I enrolled in pre-college art classes at Carnegie Mellon University and at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts where I studied with Herb Olds and Bill DeBernardi. Working with Herb and Bill definitely helped me to gain momentum as a young artist.

EH: Are there any works in particular that you saw as a very young person that formed your idea of the kind of painter you want to be?

DS: I have some vivid memories of a visit to the National Gallery when I was around 13, when I first grasped that people could commit their lives to painting. We had been there before but this time I saw things differently, maybe I was ready to let it all in. It floored me. I was actually very uneasy about it, very unsure of what to do with the feelings I had. It wasn’t about sadness or happiness, or really any one nameable emotion, but a sort of aesthetic charge that got tangled up in a variety of memories and associations. The sense of touch needed to make great paintings carries a very particular type of information. At times it feels like a transmission line carrying a charge directly to the nervous system, as the eyes of the painter connects with those of the viewer.

The rooms of Rembrandt and Vermeer, Ingres and David, Titian and da Vinci all made my head spin. At the time, I was most interested in the impressionists and post-impressionists because the visual vibrations seemed the most true to vision, simultaneously present and fleeting. I loved watching the paint dance in and out of form, changing from a volume to a simple smear. This was the first time I was acutely aware of how entrancing paint was as a material. I’m still amazed that this primitive material can be simultaneously humble and unspeakably beautiful, mindless and full of wisdom. I teared up that day, but didn’t let on. It’s always easier to let your emotions show in a dark theater, than in a fully lit gallery, isn’t it?

I should also say that my cumulative experiences with paintings at museums in Pittsburgh have had a profound impact on my visual and cultural awareness. The Carnegie Museum has some wonderful pieces in the permanent collections, in particular a beautiful Venetian interior by Sargent, some knockouts by Degas and Corot, and several works by Giacometti that never cease to amaze me. The Frick Museum has the beautiful Rubens portrait of Charlotte-Marguerite de Montmorency. I also remember two fantastic painting shows at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts when Murray Horne was the curator, one of Pittsburgh’s own Raymond Saunders and the other of Odd Nerdrum’s early and mid-career work.

EH: Not too many people seem to talk about that period when we are freshly out of school and suddenly thrust upon the world. Can you tell us a little about that time of life for you?

DS: Times of transition are always difficult. I had three major transitions, one on leaving undergrad then again after grad-school and then my move back to Pittsburgh. Each time I found myself in a new part of the art world and I’ll share a little about each.

After graduating from Syracuse I moved back to Pittsburgh for a year before I applied to graduate school. My first job was as a bartender and then I started working as an installer at the Carnegie Museum and Wood Street Galleries. I also taught a class or two at local arts centers. My main focus at the time was really on developing my studio work, exhibiting and getting ready for graduate school. I had known since my sophomore year of college that I wanted to be a professor, so an MFA was essential.

I visited and applied to several schools on the east coast and ultimately chose to attend the Hoffberger School of Painting at MICA. Grace Hartigan, the founding director of the program, was the main faculty presence and her work, life history and ideas about painting left a powerful impression on all of us. I was also fortunate to get to know some of the many wonderful artists and thinkers there like Bill Schmidt, Raoul Middleman, Karen Gunderson, Philip Koch, Leslie King-Hammond, James Hennessey and many others.

Leaving grad school was a similar experience to leaving undergrad, in that I felt uncertain about the future and was hungry for opportunities. My girlfriend Susheela (who is now my wife) and I moved to Philadelphia and I started knocking on doors, searching out opportunities and meeting new people. I had a small network of friends there who were architects and they helped me connect with a design-build architecture firm. I started working with them to create plaster finishes and decorative carpentry for cash wraps for the retail store Anthropologie, as well as general residential renovations. I learned so many transferable skills and am thankful for the opportunities they provided.

I was also teaching night classes at Philadelphia University for a time and exhibiting works including a group show at the Mattress Factory. I found a studio in the now demolished Gilbert Building near PAFA and worked as much as I was able. At the time, the building housed the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Vox Populi Gallery and other arts cooperatives.

Eventually, we moved back to Pittsburgh so Susheela could attend graduate school and I was lucky to serve as the Curator and Director of the American Jewish Museum. What I discovered though the interview process and in the first few months on the job, was that my experiences in art history and critical theory classes had prepared me well to write grant narratives, curatorial essays and press releases. My earlier experiences as a museum installer and craftsman were also very helpful and prepared me with a sense of how to design, troubleshoot and hang an exhibition. I learned so much in my time at the AJM, but knew that teaching was better suited for me.

What all of these transitional anecdotes should make clear is that being an artist is a hustle and it is important to be proactive, self-disciplined and adaptable. My advice to young artists is to work hard, seek out opportunities and keep your eyes and ears open. Also, try to surround yourself with friends and loved ones who will help you protect the mental space necessary to make your work. Share what you do. Submit work for open calls, apply for residencies and grants, join an arts organization, and stay active.

EH: How do you choose the subjects of your paintings?

DS: In my recent work all of my subjects and motifs are in my life in some way. I know all of the people, spaces, and objects, through direct and intimate experience. I’ve chosen to narrow my focus in part, because I need sustained contact to make my paintings over long periods of time, but also because I need to feel emotionally connected to what I’m doing. Critical distance is important, but too much leaves me cold.

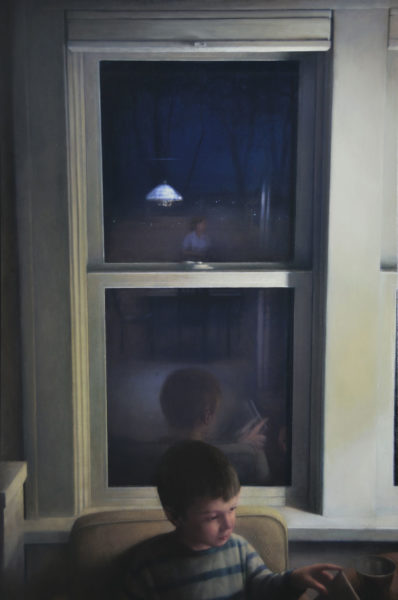

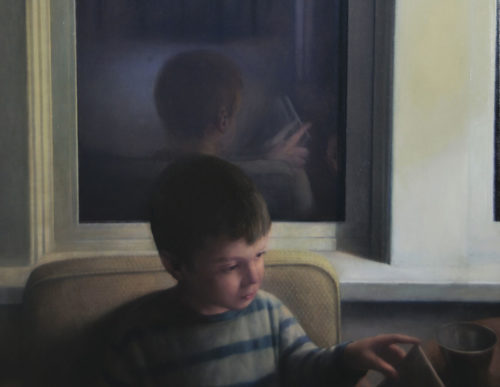

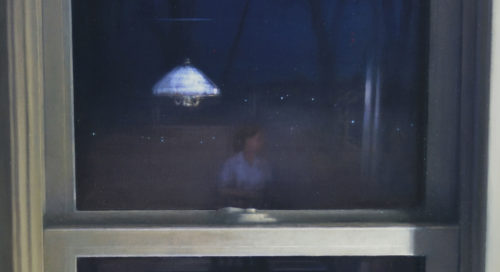

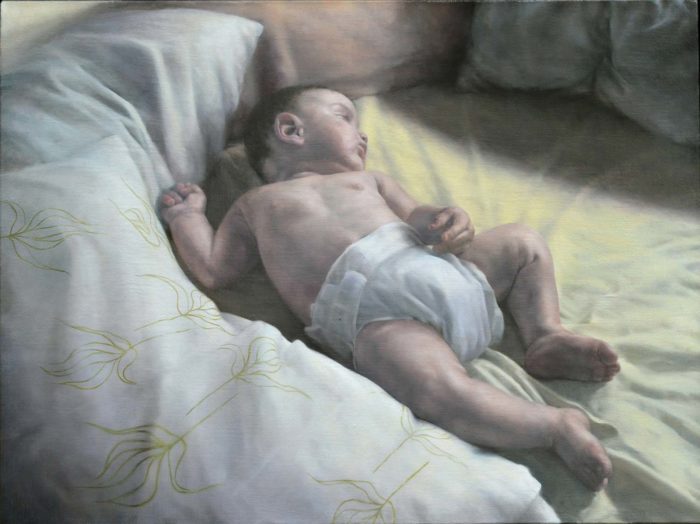

One thing connects to another and works unfold. I may have a fascination that I can’t shake or I may see something that feels like an embodiment of my state of being. It could be a pattern of light and shadow on the ground, a face in crowd, or a fragment from a story I’ve read, a melody I’ve heard. Often I find that the most intriguing ideas for paintings come from my family and friends, because I share my life with them. When my son Ravi was born I made several paintings of him sleeping and several of my wife Susheela. We were starting our new lives together and there was nothing I wanted to paint more.

Compositions develop out of their own nature and through chance encounters with light or visual juxtapositions, but I’m not so naïve as to think that my choices in pictorial content are just formal. Like all people, my choices are driven by deep-seated psychological desires and fears. I feel a sense of responsibility for what I paint, I want to know that I am engaged in something meaningful and honest.

Painting as an intellectual discipline is self-reflexive and to my mind, great paintings exist in dialog with other works around them or before them, not alone or without context. Museums are a resource, and the works they house teach and set expectations about what people are capable of. I agree with Cézanne’s dictum that “the path to Nature lies through the Louvre, and to the Louvre through Nature.”

EH: How does your teaching inform on your artwork and vice-versa?

DS: Painting and teaching are now intertwined for me, as I grow as an artist so too as a teacher. My pedagogy is a reflection of my current understanding of painting, but I am careful to not be orthodox in my approach, so as to not limit what is possible for students in the studio. I provide structure and teach observational drawing and painting techniques, but I also work hard to make a permissive environment for students to explore their own fascinations. Because my early professional and artistic life was so varied, I think I bring that curiosity about all aspects of the contemporary art world to the classroom.

Growing up in Pittsburgh, I was in exposed with wide perspectives on contemporary art through the Carnegie International exhibitions, and the expansive and far ranging exhibitions at the Mattress Factory and Warhol Museum. As a viewer, I have endless curiosity about what I see and try not to discriminate about categories of art making or discount works prematurely.

Both teaching and being a father have, in their own ways, tempered my mind. When I was a teenager and even in college, I was more volatile, excitable with my moods and work. Explorations were wide ranging, and I followed my intuition and desires. Now I find, that while I remain open as viewer, I have become more sensitive to what works I truly connect with and filter what enters into my deeper studio investigations.

One of the great challenges in life is balancing external demands on our time and energy with our private concerns and personal investigations. While I feel very inspired by my students and colleagues, I often struggle to balance my ambitions in the studio with a large to-do list. My studio is in my home and I try to work daily, in manageable chunks of time. Some days I can get 8 hours in, others only 1 or 2, and sometimes all I have energy for is looking. Summer and winter breaks are when I can really get things accomplished in the studio.

Being truly present in the studio does require constant engagement and maximum effort. I want my work to be on my mind continually and if my connection slips, I’m not really myself. This is at the heart of being an artist; it is not only a profession, but also a heightened sense of being.

EH: When asked about your creative process in an earlier interview, you answered very beautifully with the following:

My work is often born of unexpected visual encounters that fascinate and tug at me. I trust those rare moments of heightened visual perception, when I’m shaken out of my daily concerns. It is this trust in a glance that leads to sustained observation and enduring, meaningful experiences.

As a painting develops in and out of months, the surface gains a history and begins to hold a measured intensity and an increasingly complex technical narrative. Paintings carry a physical index of the painter’s accumulated decisions and are both objectiverecords and a distillation of memories.”

When you spend months on a single painting, how do you preserve the power contained in the experience of the initial glance?

DS: Life is fleeting but we try to hold onto it, embrace it. Painting is a very particular way to share our visual experiences. The process of painting slows me way down, which unto itself is significant in our modern world. It allows me to be fully present in the moment and open to experiences.

One of my favorite authors, Paul Auster wrote, “Stories happen only to those who are able to tell them, someone once said. In the same way, perhaps, experiences present themselves only to those who are able to have them.”

I don’t set out to spend months on a painting but I often need extended time to make determinations about what is most important in a given work. This often translates to countless hours putting paint to canvas, but it can also mean spending time looking and thinking, or even setting it aside for a time. At any point in this process, I give myself license to change or remove elements from the composition. Accounting for change and the readiness to make it happen is essential to painting. Learning to paint is learning to re-paint.

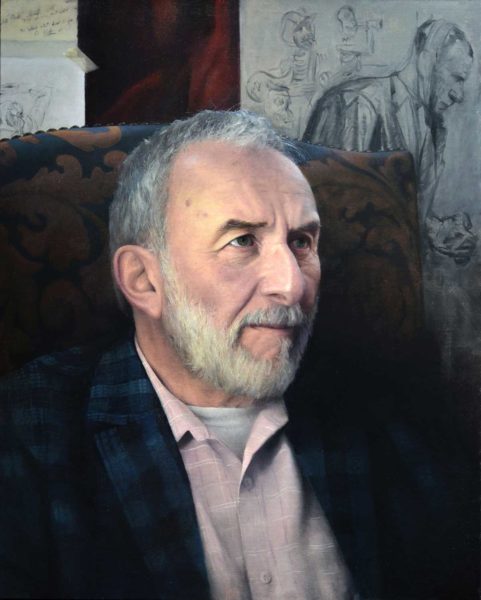

I recently completed a portrait of my friend Graham Shearing in his home, surrounded by his collection. We met most Fridays over the course of a year for three-hour sessions and then I worked on the painting at my studio in between meetings using sketches and photographs as a guide.

In addition to Graham’s likeness, the motif contains dozens of artifacts, objects, paintings and prints that he has collected over a lifetime. I must have repainted the table-scape over a dozen times, trying to understand and refine pictorial relationships. The value and color space was also endlessly adjusted with glazes and scumbles that alternately obscured and articulated each form and their interrelations. It was an extreme example of painting as adjustment.

A few years ago, I rediscovered a wonderful children’s book written by Margaret Wise Brown in 1949 called “The Important Book.” Through a series of poems, the book addresses the author’s perception of the common world and she orders her observations in poetic rhythm. For example:

The important thing about the sky is that it is always there. It is true that it is blue, and high, and full of clouds, and made of air. But the important thing about the sky is that it is always there.” – Margaret Wise Brown

In encountering the world we all have a different way of ordering our perception. When reading the book, my five-year-old son certainly had some different thoughts about what was most important. Being captivated or inspired by the visual world is not a given, you have to be open to it, responsive to it. So is true in the processes of painting.

I am interested in painting that shows us poetic insight about the motif and conventions that surround it, not painting that is just a litany of observations. Figurative painting is not simply about verisimilitude, or technical acuity, rather it is the application of techniques that serve larger insights. To my mind, mastery in the arts is not about the imposition of the artist’s will or a projection of historical styles, but about how responsive we are to the world and those around us and how we allow ourselves to be shaped by this interaction.

James Elkins in his book “The Object Stares Back” explores and articulates this idea so eloquently:

Vision, I have argued, is not the simple thing it is imagined to be. It has to do with desire and possessiveness more than mechanical navigation, and it entangles us in a skein of changing relations with objects and people. In particular, vision helps us to know what we are like: we watch versions of ourselves in people and objects, and by attending to them we adjust our sense of what we are.” – James Elkins

EH: When you use photo reference in your work, how do you manage to take the painting or drawing beyond the level of a mere copy into something that transcends the reference? I ask this because so many young painters get stuck just there.

DS: Photography in the hands of painters can be liberating, but overuse of photography is certainly a problem for painters. From a mechanical perspective the camera often leaves out much of the subtlety of human vision, and the fixed image limits our awareness of change and subtle cues about depth, form and air. As our eyes move from bright forms to shadowed areas, they are continually adapting by controlling the aperture of our pupils and centering our field of vision on our fovea. When I gather photographic references I find that multiple exposures are needed to provide the necessary information in both the shadows and lights.

Throughout history, artists have used optical devices to help reduce extraneous information or alter their perception of a motif. Mirrors, lenses, prisms and colored glass have all proven invaluable tools to help us see form and light in different ways and increase our ability to distill a pictorial idea. Of course, painters regularly use their eyelids to squint or let their eyes go out of focus to alter their visual impressions and “… find the spirit in the mass” as David Bomberg used to say.

If we draw only from a single still image, then we risk losing touch with the nature of our own perception, which is fragmented. Over use of photography in painting can limit pictorial and artistic growth.

There is a difference between sensory responses and emotional resonance. I generally feel that paintings act on me in a visceral and sensory way first, and then over time they begin to hold some sort of emotional identity. How do we name the emotions or ideas we encounter when we listen to a piece of music, a film or a painting? In a portrait, can we feel a depth of emotion and complexity of identity or is it just a superficial resemblance? I would argue that without direct, sustained engagement or intimate knowledge of a sitter, we are in danger of chasing shadows. It is so hard to make a good painting and there are so few truly great ones, why would we start out with a disadvantage, keeping the motif at arms length with a photograph? Go to the source, and build a human relationship.

EH: Can you tell us a bit about your painting heroes and what most inspires you?

DS: There is a causal chain between paintings I seek out and current problems I’m working on in the studio. Reading paintings helps me to find answers to questions I have or at least gives me the confidence to carry on. If I can witness poetry in paint first hand and know it to be real, then perhaps I can make something like that happen in my own work.

To develop as a painter, work at the canvas is primary, but it is also necessary to seek out great paintings. This holds true of other creative disciplines. To be a great writer, for instance, you can’t just go and read a dinner menu and expect to grow, you need to seek out other writers who have or are reaching for something significant and honest. I’m always looking at paintings, but over the years, I have become more sensitive to what works I truly connect with.

My view of art history is not necessarily linear and I often collapse large distances in time to preference visual connections or visual threads running through painting history. I have an affinity for the contemplative and distilled pictorial worlds of Vermeer and Hammershøi and they feel as relevant and accessible to me as Michaël Borremans or Ann Gale.

When I lived in Florence, Italy as an undergraduate, I was dumbstruck by what I was seeing, but once I got over that initial jolt, it began to feel like a true homecoming. It was a life changing experience for me on so many levels. I was drawing constantly. In particular, I was trying to internalize the marks I witnessed in drawings by Michelangelo, del Sarto and Pontormo. One morning, in the shower, I looked down at my leg and saw sanguine lines and hatches super imposed on my vision, just as Pontormo might have drawn the form. That’s when I knew it was indelibly part of me.

In recent years, I’ve been particularly interested in the contemporary painters Antonio Lopez Garcia, Vincent Desiderio and Israel Hershberg whom I have had the great pleasure of getting to know through his summer painting program in Civita Castellana, Italy. Though they are each approaching observational or realist painting from unique perspectives, they have all helped me to maintain my bearing as a painter. When Jerome Witkin introduced Antonio Lopez Garcia’s work to me years ago, it demonstrated that that desire can deepen with sustained engagement, that the mediation becomes deeper the more you look.

EH: Congratulations to you on your painting of Jerome Witkin getting selected for the BP Portrait Award at the National Portrait Gallery in London! That’s a big deal. It’s clear that the subject means so much to you as a mentor. I’d love to hear more about some of what you learned from him and also anything you would like to share with us about this painting in particular.

DS: Thank you, I am honored and proud to be part of the exhibition. The opening was thrilling and I had the opportunity to meet so many wonderful international artists in person. I had never been to London before, so this was a wonderful occasion to soak it all in. What an amazing city!

The idea to paint Jerome was percolating in my head for years until I finally worked up the courage to write him a letter. We had corresponded via letters over the years and had gotten together a couple of times, but I was unsure if he would agree to sit for me. He called a few days later and said that he would be happy to. We arranged a week in June and I traveled up with my family on a trip I won’t forget.

I hadn’t been back to Syracuse since graduation in 1998 and walking around campus brought back so many memories. The following morning was sunny and warm when I arrived at Jerome’s house. He greeted me and led me around to the back yard where his studio sits high up on stilts. Stepping into his studio I was faced with sweeping paintings on all sides, storage racks bursting with works and walls of drawings, notes, family photographs and letters, taped and tacked up. To one side is a doorway that opens into a chamber. It is here that Jerome stages models in controlled lighting, while his canvas can be viewed in daylight in the main space.

Almost all of the visible paintings were related to his family history, from tumultuous narratives of his father and mother, to somber and touching depictions of his son Andrew who passed away a few years ago at the age of 16 from an illness he struggled with throughout his life. One of the paintings depicted his wife sitting alone, at night, in their son’s bedroom holding his clothes in her hands. To her left, just beyond the room, Andrew looks longing at his mother from a cold astral plane, awash in green light. At the rear of the space was an amazing life-sized charcoal drawing of Anne Frank with hands raised to her chest and her mouth open in speech or song.

I thought to myself, “How do I begin to paint my teacher, with the psychological weight of this room around me? Pick up a brush, slow down and look.” Jerome and I talked for hours, and laughed a lot. For those who know Jerome, he has a penchant for bad/good jokes and biting humor. When we were silent, his eyes fixed on his own work in progress. That is that state in which I’ve chosen to depict him, in deep reflection. In my painting I’ve included fragments of studies on the wall behind him. Specifically a drawing for a painting of his sister, another for a cycle of works about Vincent Van Gogh and the passage of dark red is from a pastel study of George de la Tour.

Pietà, a sympathetic sorrow, this is at the core of Jerome’s work and his teaching. In his classes he talked most often about Rembrandt, Michelangelo, Kollwitz, and Gross and his belief that artists have a moral imperative to address human suffering. He instructed us to make countless master copies to internalize the works. It is clear that he was doing the same; these artists feel present in his own paintings. In his classes, drawing was never addressed as an academic exercise but as a way to express our humanity.

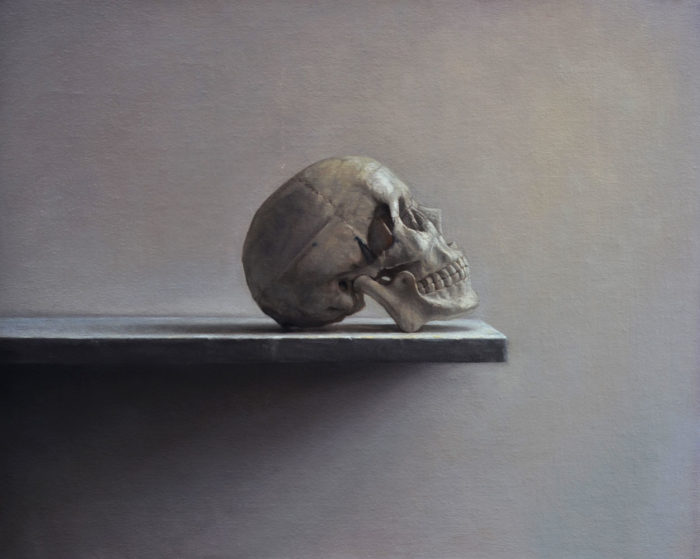

I took a semester-long course with Jerome on artistic anatomy and we all spent the semester pouring over books and diagrams, drawing from live models and trying to visualize internal structures. But what really made it palpable were the classes spent drawing from cadavers at the medical school. It was not enough to approach the subject from a critical distance; he wanted us to engage with the heavier realities of our bodies and existence.

My portrait of Jerome is about my relationship with him as a teacher and mentor, but it is also a summation of my thoughts as a painter. At its best, portraiture shows us both the sitter and the artist, a comingling of lives, fixed in paint. I hope that my efforts as a painter inspire my students as much as Jerome did for me.

EH: There’s a real community of us figurative painters out there in the world, struggling to make a mark that matters. What advice has proven to be the most helpful to you over the years that you can share with us?

DS: I was just saying to a friend the other day that from a wide historical view, figurative painting is a constant, but in modern times it’s a dark horse. The ‘return’ of figuration is already underway, with many new voices and approaches in play. I think we’re at the edge of something spectacular.

Just look at the effect that the recent Presidential portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama has had on our global awareness of portraiture. The paintings are significant in so many ways, first and foremost because they honor our first African-American President and First Lady, but also because the artists Kehinde Wilde and Amy Sherald are the first African-American painters to be chosen for this honor. They both made strong paintings unlike any Presidential portraits before them. Amy and I went to grad-school together and I am so proud of what she has accomplished! I’m sure we’ve all now seen photographs in the news of the little girl in the pink coat transfixed on the portrait of Michelle Obama, it’s wonderful and empowering. This illustrates how innately powerful figurative painting is, because it shows us ourselves and it does it through human touch.

There are a few remarks made by my professors and mentors that I’m happy to share. Sarah McCoubrey offered some parting encouragement at my senior exhibition at Syracuse, “…if the work needs to be made, trust that you will find a way to make it.” Jerome Witkin always used to ask us “How bad do you want it? How much are you willing to give to make great paintings? Do you want it as much as Michaelangelo or Rembrandt?” Grace Hartigan often talked with me about working to make sense out of the fragments of perception and how the struggle to do so is part and parcel of the human drama. Nearing graduation she would repeat the adage “Trust that if you leap a net will appear.”

One has to be driven, even ambitious to be an artist. But that doesn’t mean we can’t also be generous and supportive of others. What you give will come back to you ten fold. Kindness and generosity can be the tide that raises all ships.

Thanks for sharing. Inspiring perspective on art regardless of the genre we work in. I also had Herb Olds an instructor at CMU, he was a true educator as well as a good Artist.

I’m glad you enjoyed the interview, Samira. Herb was the first teacher that got me thinking about human anatomy and how important underlying structure is to portraiture. He was an inspiring teacher to be sure.

Thank you for sharing this interview. I was not aware of this artist, but find I share many of his concerns about painting.

Glad to hear the interview resonated with you Katie. Cheers – David

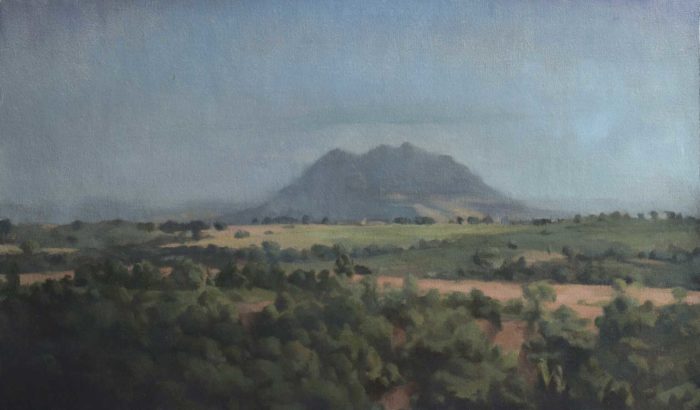

I am so glad to know about your work and sad that I am only learning about it now. Graham has several times introduced me to an artist that I like so much that I want to own their work. I am especially attracted to your landscapes.

Thank you for the kind words Ann, I appreciate it! I hope we’ll have a chance to meet at some point. Best – David