Last October, I had the pleasure of meeting Marie Riccio at her solo exhibition, Still Echoes, at The Painting Center and the Small Works Invitational at First Street Gallery. Riccio’s work drew my attention for the sophistication of her compositions and subtle yet powerful use of color as tone that brings an exceptional depth and nuance to her modern still-life setups of commonplace objects, transforming them into subjects of contemplation and aesthetic significance. This ability to elevate the ordinary to something profound through the formal language of painting prompted me to ask her for an interview so that we could learn about her artistic methodology and background.

Riccio obtained her B.F.A from SUNY Purchase and her MFA from the University of Pennsylvania, where she studied with Neil Welliver. Her curatorial projects include still life group exhibits at both The Washington Studio School, DC and at VisArts Rockville, MD. She has exhibited across New York, Maryland, and the Washington DC area and is represented by First Street Gallery, NYC and TAG/The Artists Gallery, Frederick, MD.

Larry Groff: How has your approach to still-life painting evolved since your early days as an artist? Are there any pivotal moments or influences that have shaped this evolution?

Marie Riccio: Like most artists, I have always loved drawing and spent much of my childhood drawing in my room. My love of color has always been present, and I have memories of colors and how they made me feel. However, I didn’t start to paint until after I left undergrad.

As an undergrad student at SUNY Purchase, there were two classes that really made a great impression on me. One was an art history class taught by art historian Irving Sandler, author of The Triumph of American Painting, who each Wednesday took us into NYC to the galleries. He introduced us to many gallery owners and artists and made visiting galleries less intimidating. That experience opened me up to a world of art beyond what I saw in the oversized book section of my local library. The other was a class based on the book, Interaction of Color, taught by Sewell Sillman, a student of Joseph Albers, that I took as an undergrad and then again as a grad student. The class changed my understanding and awareness of color and started me on the path I am still on today. However, it was in graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania that I made the greatest change.

I arrived at Penn as an abstract painter, and Neil Welliver encouraged me to look at my surroundings and paint from life. I started with the objects in my studio. Those were my first still-life paintings. I could see colors that I could not imagine when painting abstractly. It was all very exciting.

I also started painting landscapes during that time and continue to do so, but the still life is where I feel I can explore color in the way that most interests me. I have continued to be an observational painter working in oil and sometimes gouache.

LG: How has your early experience as an abstract painter influenced your current work?

Marie Riccio: Several years ago, I started revisiting my abstract work roots within my still-life paintings. That interest has developed into evolving ideas about how light is described. My thoughts about light can be described in two different ways; the light within flat shapes of color that radiate light (from my abstract roots) and the light described by rendering value (realism).

I am inspired by painters who describe light in these different ways, especially Antonio Lopez Garcia’s exquisite ability to create form and atmosphere through value, Hans Hofmann’s abstract brush strokes and flat rectangles of color that waffle in and out of space, and Vermeer’s beautifully rendered soft, warm directional light. I also found inspiration in Joseph Albers’s Homage to the Square, where colors radiate the light of varying degrees, and bouncing color plays in the space, Fairfield Porter’s flat color shapes describing light, Euan Uglow’s color and shapes describing form, and Morandi’s exquisite, subtle color and compositions. I am fascinated by the possibility of having both approaches coexisting in my work.

LG: In your still-life paintings, you often depict commonly used still-life items such as brightly colored backgrounds using drapery and similar materials, pots, and vases, various natural forms, ribbons, and other objects that provide structure and a basis for color harmonies. Can you walk us through the process of selecting these items? Do you look for specific characteristics, or is it more of an intuitive choice?

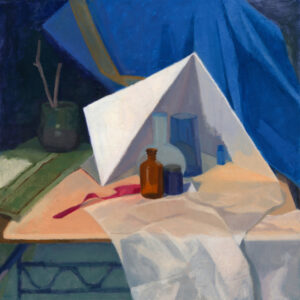

Marie Riccio: I usually begin my work with an intuitive approach. I have still-life objects scattered around my studio and will look for something that catches my eye; a color, a shape, or the curve of a bowl. I place the object on the table and start to add more objects. Slowly I begin to see a color tone develop and will add additional objects to help emphasize that color mood. I then start to visualize the composition and how I want the eye to move within the painting.

The addition of ribbons, sticks, marbles, etc reinforces these compositional decisions. I take into consideration which elements will play the dominant role in the composition, the objects that I want to steal the show. I also add patterned cloth or solid pieces of colored paper to activate the space.

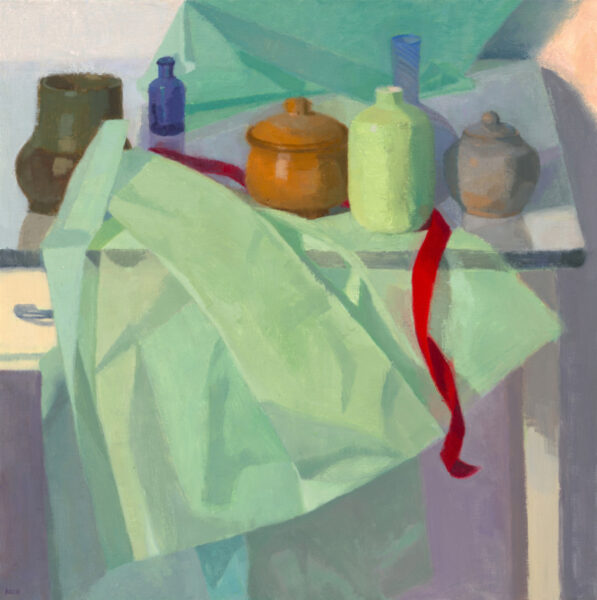

An alternate approach for me is to start from some inspiration that has formed in my thoughts. That might be a color combination I have been daydreaming about or the re-creation of a composition from a work of art that inspired me. For example, while observing Wayne Thiebaud’s San Francisco painting, Two Streets Down, I was intrigued by how he placed the horizon line towards the top of the painting, how the area above draws you back into that space, and how the area below the horizon appears flat. This composition influenced my painting Traveling Red.

LG: Are you mainly interested in a more modernist formalist approach to painting, as opposed to an expressionistic one? If so, why?

Marie Riccio: I don’t usually include objects in my paintings that would give you a sense of a particular time. For example, you probably won’t see a fashionable piece of clothing or references to pop culture. That’s not to say that they wouldn’t creep into a painting at times, though they would be used in a more modernist approach; for their shape, pattern, or color rather than to provide a direct narrative quality.

I started out as an abstract painter, and my interest in shapes of color interacting with adjacent colors has carried over into my still-life work. When I begin a painting, my touch is expressionistic and open as I draw and paint color notes on the surface with my brush and search for the placement of the elements. This expressive search begins the process of connecting to what I am looking at and eventually becomes buried as I work my way through the painting to a refinement of the main interests I am after.

LG: You’ve mentioned on your website that your still-life paintings sometimes reveal personal meanings from the process itself. Is there ever a starting narrative, or does everything evolve more organically along with the painting?

Marie Riccio: Each piece begins with a formal approach without any intent towards a particular meaning or narrative. The work changes through the process. I add things, remove objects, repaint an object a little to the left or to the right, making decisions to arrive at a painting that feels right, balanced.

This evolving process is very meditative for me. I get lost in thought and feel my way through the painting process. As I spend time with the painting, I develop a relationship with it, and the objects begin to take on personal qualities. I see the objects interacting with each other, and their environment and characters announce their presence to me. This sometimes happens through their proximity to each other, their interacting color reflections, or how an object dominates its surroundings.

When I have a sense of what the painting is about for me, I am able to name the painting, and I know I am done. I don’t expect the viewer to know what that meaning is, but I hope they get a sense that something is happening in the painting. For example, in Amongst the Turmoil, when I started this painting, I was interested in the formal idea of playing with contrast: two very dark objects that would connect as one shape and contrasted by translucent white tissue paper. During the process, the tissue paper was reshaped into a curve that leads your eye to the dark bottles. The curves of the patterned red cloth were moved to echo the opposite curve, a reflection of the tissue paper reinforcing the composition. A yellow ribbon was added to emphasize the curves in the painting, creating a sense of chaos.

During the time this painting was painted, our two children had moved home from college, and my husband was working at home due to Covid shutdowns. None of us were very happy being restricted to the house, and my husband and I had to stick together and hold down the fort during all the emotional turmoil. For me, this scenario is reflected in this painting. Many of my paintings have meaningful personal stories associated with them.

LG: What can you say about the emotional qualities of your still-life paintings, and how does this relate to your compositional choices? Are there particular arrangements of shapes that you find more conducive to expression?

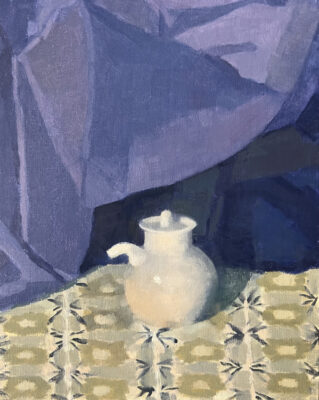

Marie Riccio: The emotional qualities of my paintings are expressed through both color and composition. Different colors and color combinations, subtle color changes, and hard and soft edges create the emotional quality of the work.

The emotional content of a composition also concerns relationships, how patterns are repeated, how connections are made, and how different forms interact. A vase may touch its neighbor or appear alone and isolated from the others. A cloth may cuddle a bowl, comforting it from other unsettling elements.

LG: In your still-life work, you’ve described a balance between the solidity of objects and the ‘chaotic side of life,’ like unraveling ribbons or crooked sticks. How do you decide on the balance between these elements in a composition? Is there a symbolic significance to this interplay in your work?

Marie Riccio: When my life feels chaotic, I seek comfort in paintings with a sense of stillness. They help ground me, and I find the quiet stillness of a painting to be calming. I am drawn to the grounded structure of things. Often, when I am painting, I feel objects from the inside out, as if I am inside them pushing outwards and working at understanding how much space they are occupying, how close they are to their neighbors, and that their feet are solid on the ground.

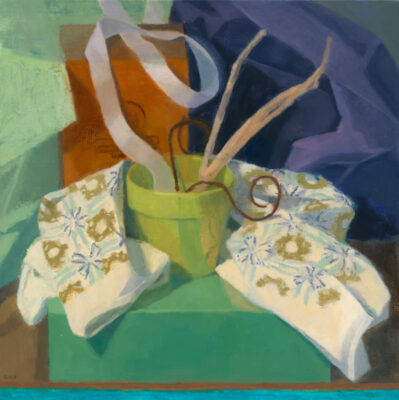

Those grounded objects are made up of ovals and straight lines. Ribbons, crooked sticks, and flowing fabric are not as easy to understand. They have the capacity to change and are unsettling. They are the spontaneity of life, the unpredictability, the fun, and I need stability to enjoy that unpredictability.

I often start by placing the stable objects first, and when I feel comfortable with their placement, I add more fluid objects to help add life to the composition and keep the image active. In my painting Crazy Times, the three centered objects were arranged first. I took care of their proximity to each other. Once established, the vines, ribbons, and flowers were added to express the whirlwind of craziness I was feeling from what was happening in the world at the time.

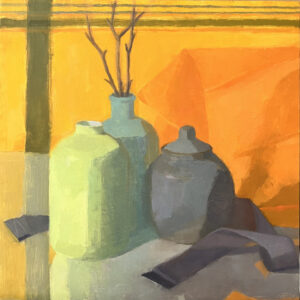

LG: Color and composition play essential roles in your paintings. Can you discuss how you use these elements to enhance the interaction between objects in your still-life setups? How do you decide on the color palette for a particular piece?

Marie Riccio: As I bring objects together, I begin to push the color mood in a direction so a dominate color family starts to emerge. In order for a strong color hue to have life I find it needs to be placed in an environment of greys or neutrals that I call “no-name colors” or “bending colors” because they have more changing power. They change their color depending on what they are next to. I find these colors exciting to paint since they involve a lot of color mixing and fine-tuning, add atmosphere to the environment, and enhance the stronger color hues. Often, they are neutral color objects, ribbons, or fabric. They can also be present in shadows or within the changing values of an element.

I frequently like to have an object or two that stands out from the crowd and the overall color tone. For me, these are the objects whose color “sings” in the painting. This can sometimes be a color that is complimentary to the overall color tone or that stands out through its value, placement, or size. For example, in the painting The Valley the orange vase towards the middle sings amongst the many no-name colors.

With composition, I am sensitive to how the objects group together, the spaces between them, and how they create connecting lines. I start to notice repeating angles, lines, and circular rhythms. I may work to emphasize aspects of the evolving structure by tweaking the composition to bring it to a stronger resolution.

LG: You’ve described your approach to still life as a process of discovery, whereas landscape painting is more reductive. Can you elaborate on the differences in your creative process between these two types of paintings?

Marie Riccio: I approach a still life as a clean slate. I get to choose the objects, the colors, the composition. I direct the process from start to finish which is very challenging but fits my personality since I enjoy problem solving.

I tend to favor a tabletop which acts as a stage for my still life. As I arrange objects, I think about how they will connect with each other as well as the space around them. I orchestrate what leads the eye into the picture plane from the wings, beginning when all the actors are on the stage. Often the characters move around and come and go until the painting is complete.

When I go outside to paint the landscape, I often see chaos in front of me that I want to calm down. So, I start by reducing what I am looking at. I group areas of value and eliminate what is not needed to create the painting I am after. This is a reductive process. In a way, I find it very freeing because the setup is there before me. This practice also helps to keep me open to new possibilities in the studio.

Both of these approaches are beneficial to my painting practice.

LG: Finding the random and unexpected in nature–through a perceptual process–can bring new life to a painting. Please share an example of a moment in your painting that unexpectedly brought new realization and power to a painting.

Marie Riccio: When I set up the still life for the painting Orange You Great, my initial intention was to play with the two colors of orange tissue paper in the background. What I didn’t expect was what the effect would be on the other elements in the painting. I saw orange everywhere. On the blue-green bottle, the tabletop, the brown ribbon. The still life was bathed in a soft orange light brought out even more by the blue/gray field under the table.

It is the process of painting that excites me; noticing the unseen, problem solving, all coupled with inner feelings. Visual language is woven into my life, and I work at painting the paintings that connect the making of art to life with the hope that the result will connect with others.

Good painting talk. Great sense of scale and proportion: both in relative sizes of objects/shapes and in relative proportions of colors.