I’m pleased to post this new interview with my friend Elizabeth Higgins, whom I know from our involvement with the Prince Street Gallery in NYC. We talked over Zoom and email to get the background for this narrative-styled interview, which is a format I hope to continue on occasion. She is having a solo exhibition from November 30 through December 24 at the Prince Street Gallery, with the reception on Thursday, Dec. 1, 5-8 pm, How the Light Gets In, showing her many new paintings and monotypes. She also has a show at the George Billis Gallery in Westport, CT (Nov 15-Dec 30, 2022).

She was also recently included group show this past March – Light of Day, The Language of Landscape, Curated by Karen Wilkin, which showed at the Westbeth Gallery in NYC along with renowned artists Lois Dodd, Albert Kresch, Stanley Lewis, and several others.

Karen Wilkin stated in her catalog essay for the exhibition Light of Day, The Language of Landscape:

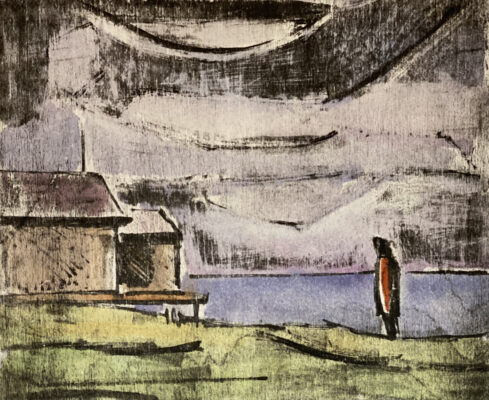

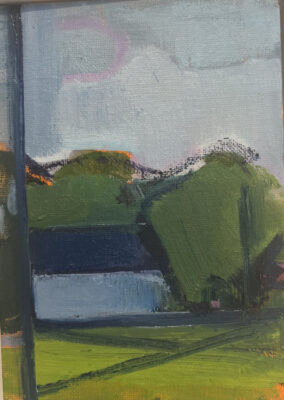

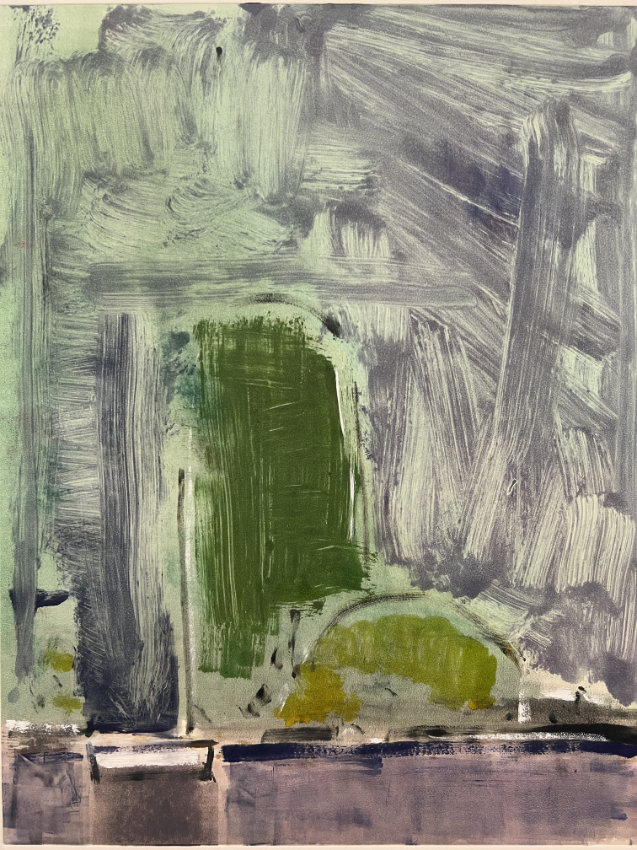

“Elizabeth Higgins distills her images from observation, often paring her images down to large elemental areas; dramatic skies or expanses of water can dominate the canvas, but also read as independent shapes. In other works, she frames more complex notations with broad planes that can be rationalized anecdotally but also functions as big abstract elements.” Karen Wilkin

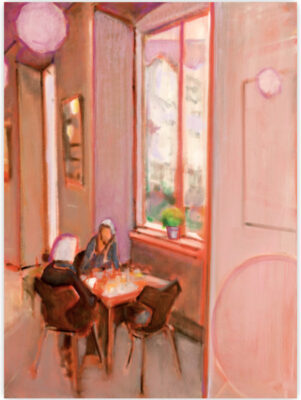

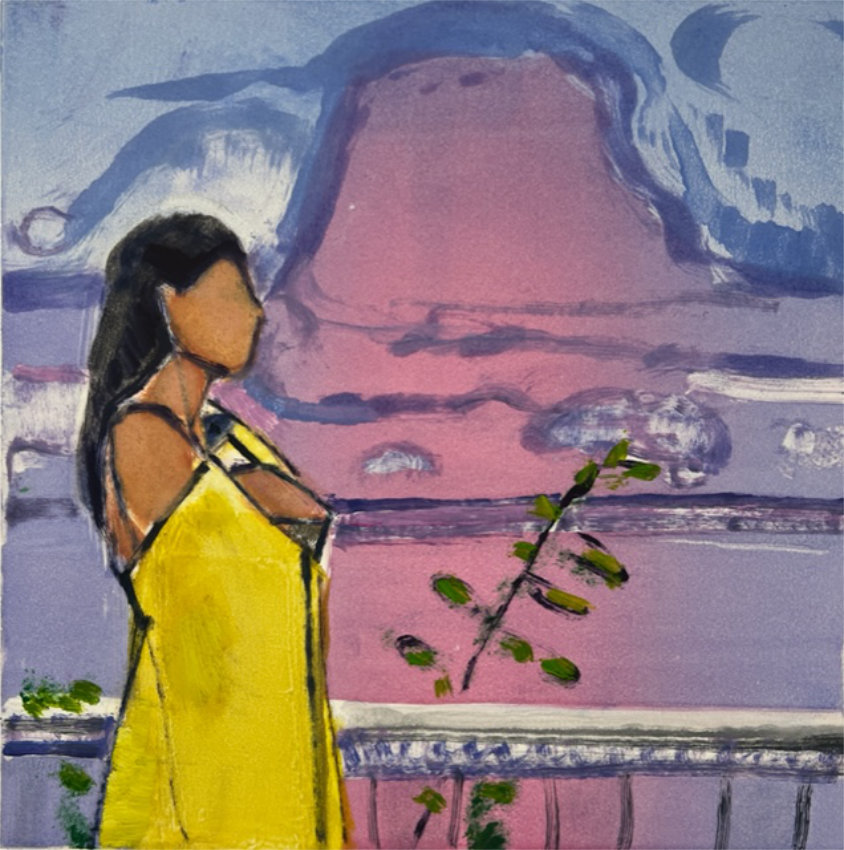

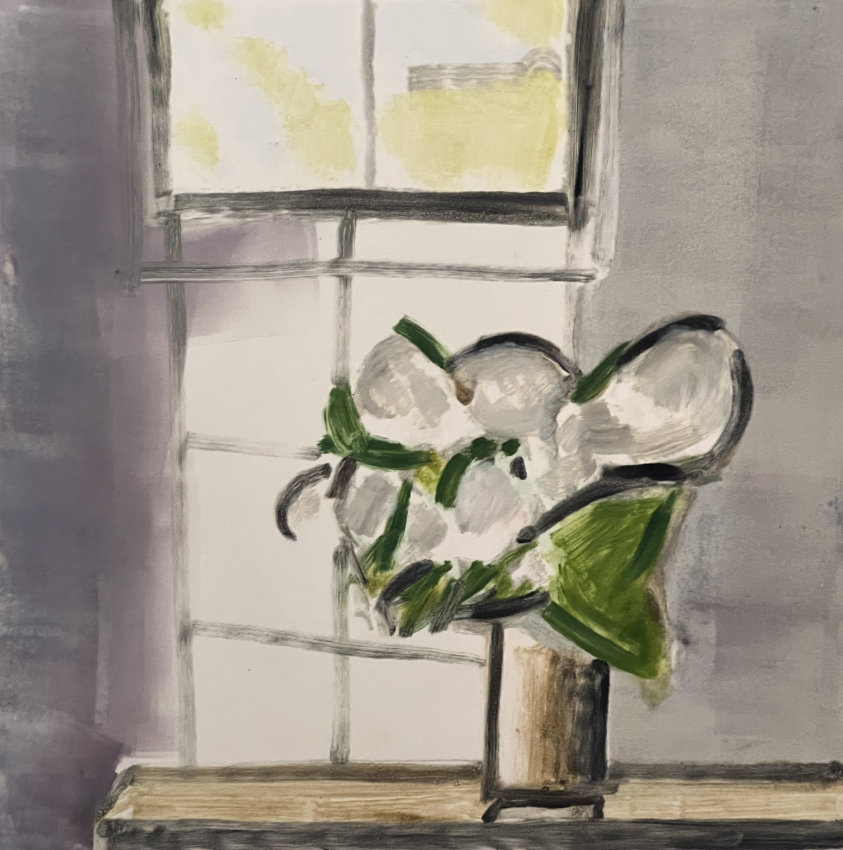

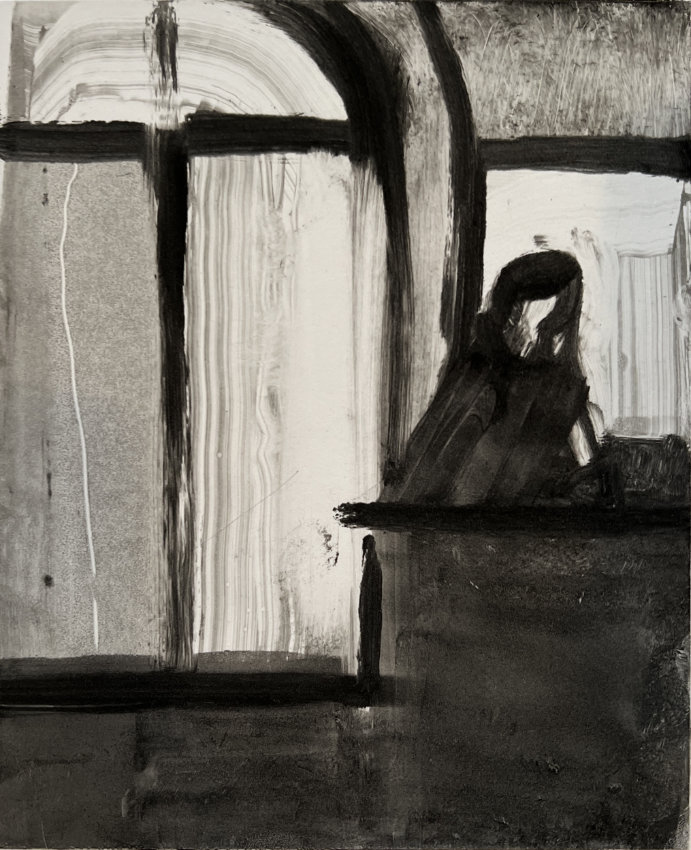

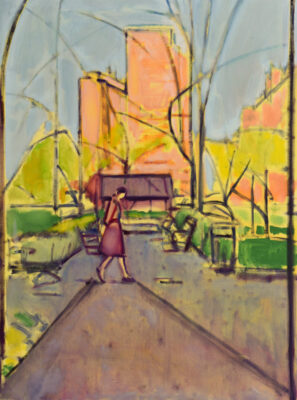

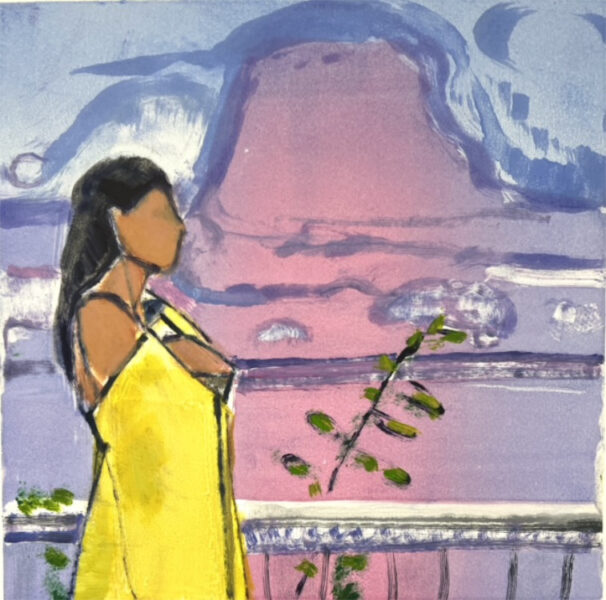

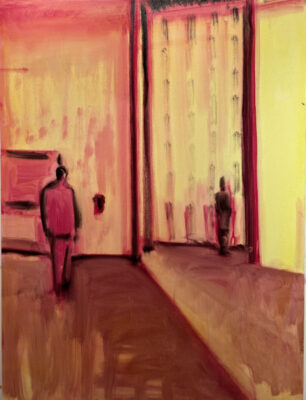

Higgins designs her paintings with vibrant color and expressive paint handling that accentuates the feeling of a radiant pictorial light that illuminates both her physical and emotional worlds. Her scenes often include relatively small simplified figures in a large interior space, turned away from us. These figures often avoid facial details, perhaps representing an idea or feeling about a family member or friend. They are often seen in contemplative poses, looking out a window, reading a book, walking along a street, or in a museum setting. There are also landscapes, sometimes of an overlooked aspect of suburban landscapes or perhaps a setting or rising sun over a pastoral, foreign setting.

Higgins’s visual investigations and color harmonies insist on the power of color, shape, and gesture to hold attention, avoid overt political or cultural commentary, and not step far beyond any expected formalist boundaries. The emotive tone and formal summations of her paintings and prints are contemplative, not confrontational.

She rejects following any dictums for what is a proper subject to paint and that it’s ok for a painting to be beautiful. She celebrates the notion from what Matisse said: “What I dream of is an art of balance, purity, and serenity… I created this work with the intentionally simple underpinning of being peaceful and restorative.”

John Goodrich wrote in his catalog essay for this show,

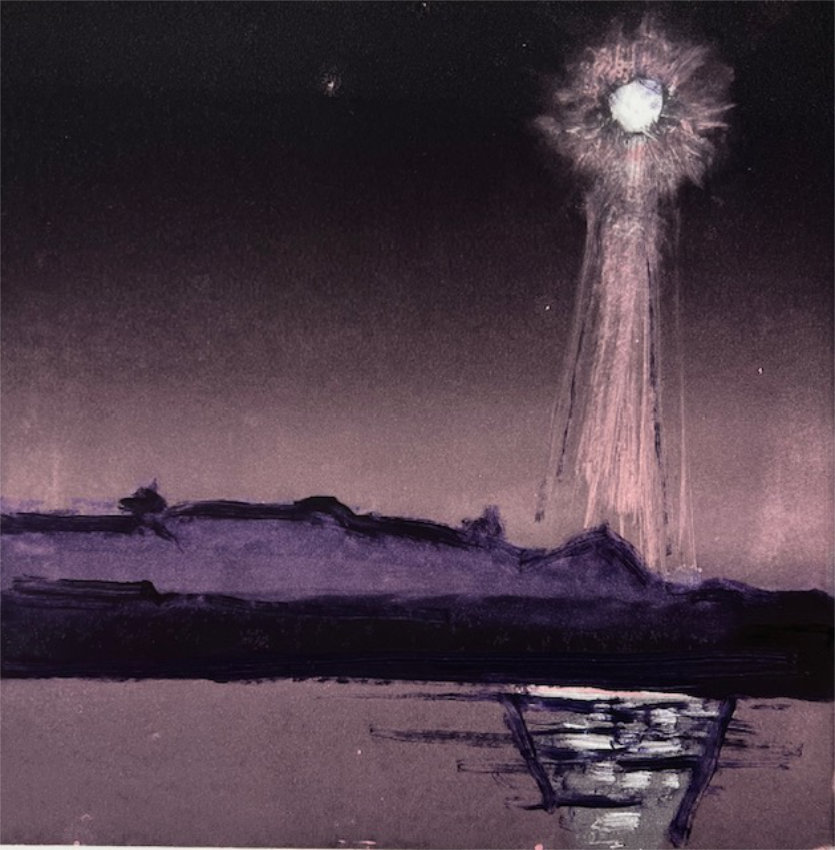

“Elizabeth Higgins is a painter clearly attuned to the workings of light. Stylistically, her paintings hit a sweet spot midway between abstraction and realism; her broadly limned forms seek a clarifying order, while her colors appeal to our deeply internalized expectations of light, lending tangible openness to expanses of air and water, and vitality to textures and contrasting details.”

Her motifs are found in the world surrounding her, and she is fortunate that it often involves scenes with radiant beauty, but light requires darkness to exist. The works in her How The Light Gets In were made during our bleak pandemic as well as the tragic sudden death of her son. For her, art-making became one of the few cracks in the darkness that eventually started to let the light in.

The title of her show is from the famous line in Canadian songwriter Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem” song…

“There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in”

Her late son, William, encouraged her during moments of doubt by saying, “What would the world be like without art and artists, Mom? It would be a wasteland.”

Elizabeth was born and raised in Toronto, Canada. Drawing was a considerable part of her early experience, a way to find refuge from the commotion of her eight siblings and attract attention from her father, a physician and medical professor, and her mother. Her parents did little to encourage her to become an artist and felt art-making might be a distracting indulgence that would discourage her from following the same academic path her brothers took to become leading medical doctors eventually.

Elizabeth told me,

“You could find me drawing at the kitchen table, the basement, in my father’s den, in my room under the eaves on the third floor – anywhere I could find a quiet place in a house filled with my eight siblings. Looking back now, this may have been a way for me to get my parents’ attention which was a hard thing to do in a family of nine…. In fact, as a fourteen-year-old, I remember copying Feruzzi’s’ “La Madonnina, 1897” for my mother, offering it up as an apology for having upset her. It stood framed on her bedside table for the rest of her life.

My parents didn’t discuss art or music with me or my three brothers or five sisters. Weekly piano and ballet lessons were my only exposure to art. My first formal art education was in my senior year of high school, where I was mentored by a teacher who encouraged me to audit her studio art class. I loved every minute of being in that classroom with the classical music playing and all the girls busy, concentrating on whatever piece they were working on. The teacher encouraged me to go and look at all the great work in the Art Gallery of Ontario, which owned Fra Angelico, Raphael, Tintoretto, the Canadian Group of Seven, Jack Bush, and Henry Moore. A new visual world opened up to me.”

She then studied art, music, and literature at Queens University in Ontario, earning her BFA. She also studied Printmaking, apprenticed under Canadian printmaker JC Heywood, and studied painting with British painters David Andrew and Ralph Allen from The Slade School.

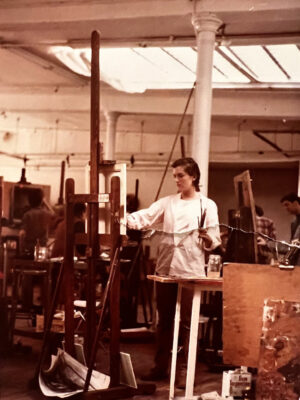

After graduating from Queens University, she moved to NYC after being accepted into the Parsons MFA program in Painting 1983-1985 and received a Helena Rubinstein Scholarship Award. She often proudly talks about her life-changing studies there with Leland Bell, Paul Resika, John Heliker, Stanley Lewis, and Robert DeNiro, Sr. I asked her who most led her in the direction of her current paintings and prints, and she said it would most likely be Robert de Niro Sr. and Leland Bell.

She told me that the one important lesson she learned was “to be committed to your process of making art and the art itself. I saw firsthand my teachers’ dedication to their work and how they led by example. But I’ve also since learned how to silence those artists’ voices and doctrines to better hear my own.”What Higgins says here reminds me of Philip Guston’s famous quote about the Studio Ghosts: “When you’re in the studio painting, there are a lot of people in there with you – your teachers, friends, painters from history, critics… and one by one if you’re really painting, they walk out. And if you’re really painting YOU walk out.”

Higgins goes on to speak about her experience studying with Leland Bell;

“He was a very supportive teacher. I would say he was a father-like figure to many of us. He was determined that we all “learned how to see” before we graduated; like a musician, he would say: you have to learn the notes before you can play. He taught us ways of seeing tone and value through color and that to make a “good picture,” and that as a painter, you had to learn how to paint the big sweeps of planes, color, form, and light. He stressed the importance of avoiding details until we got all these larger concerns right. Also, he emphasized that one should not try to “copy” nature but imply it. For instance, he would explain that Courbet would paint the large, essential shape of a tree that might visually suggest, but not actually paint, every leaf on the tree.”

Leland was an intense and analytical teacher. He taught us that painting is a continual process and that the artist’s desire to create a sense of balance and counterbalance through color, line, volume, rhythm, and light is difficult to achieve.

His admiration for his most loved painters was contagious; students would be captivated by his enthusiasm while listening to him lecturing about Mondrian, Derain, or Balthus. We would learn not only about a great work of art but how we, too, might go about making a great painting.

He was always humming music, talking about “Bird” (Charlie Parker) and other jazz giants. He once asked me about the great jazz pianist from Toronto, Oscar Peterson, where I was from, asking me if I had ever heard him play. He used to call me “Sweet Betsy from Pike,” saying that I was like “Betsy” from the ballad because I traveled far from Canada to a foreign land to make a new life, which is precisely what I did. He taught me many things and is still very much with me.”

I asked Elizabeth how her work departs from certain aspects of her teacher’s manner of working. Elizabeth said,

“I differ from Leland in that I don’t “obsessively rework” my paintings, as Leland was known to do. I must trust my voice when it says a painting is finished. Sometimes a work of art can seem effortless, which is ok too. I’ve learned that you don’t always have to struggle and labor over a piece for it to be a “good” painting. This can be seen in the work of Leland’s wife, artist Louisa Mattiasdottir, and his daughter Temma. and Lois Dodd, all of whom have an innate ability to beautifully simplify and glean the essentials of a landscape.

When I asked her about her painting process and how observation informed her work, she talked about how she avoids a set formula for making her paintings, telling me, “I’ll paint from memory, and sometimes, I paint directly from life. I don’t use a formula. I don’t necessarily search for a motif. I often come upon a familiar scene or motif I’ve seen for years that suddenly strikes me in a new way, often from how the changing light reveals some exciting new possibility.”

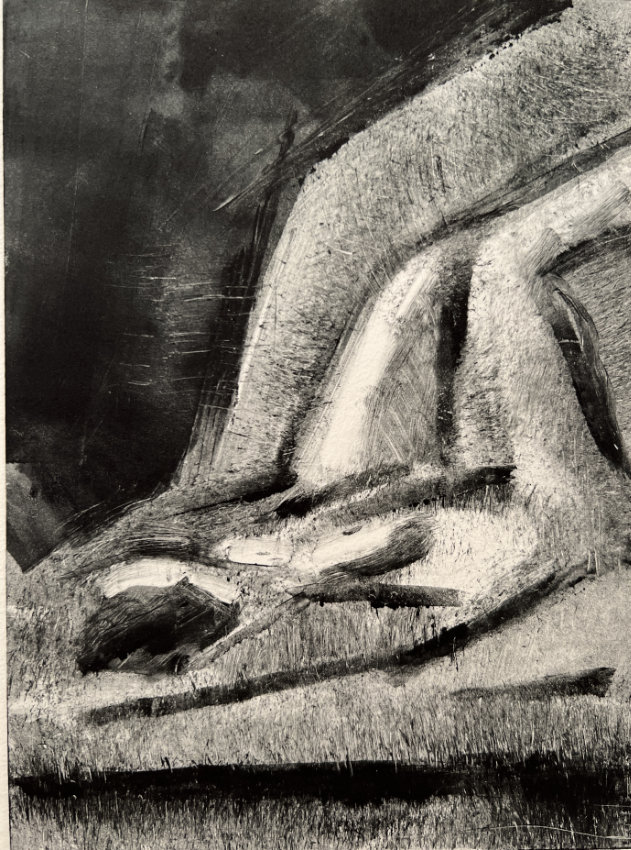

There is a close relationship between Higgins’s paintings and monotypes. The clarity and simplicity of the design and color, as well as the drawing with paint.

I asked Christopher Shore, Staff Master Printer at the Center for Contemporary Printmaking in Norwalk, CT. to say a few words about Elizabeth Higgins’ printmaking.

I asked Elizabeth to speak about her process and how she decides what to paint. Here are a few of her thoughts on this.“Watching the artist Elizabeth Higgins in the printmaking studio is such an insightful experience. Most times, the artist is alone in the painting studio, but in printmaking, working with a collaborative master printer, one gains special access into an artist’s process. Seeing Elizabeth work quickly and spontaneously, with rollers and brushes, mixing the inks and applying them to the plexiglass matrix, you can feel the engagement with, and the exploration of the composition, as it develops over a short period of time. Reworking the plate and refining the image while creating multiple print variations from the ink on the palette and the residual ink on the plate, you truly feel her process of investigation. Monotype printmaking is a relatively fast and spontaneous method of working and I am always excited to see Elizabeth grapple with the process, whetherin simple black ink or with a full range of luminous color. The results are a varied array of impressions, some complex and refined, while others loose and raw. Together they communicate a closeness to these deeply felt places that are described in her work. Elizabeth’s prints fully employ the dynamic monotype process and exemplify her commitment to the enterprise of her visual expression.” – Christopher Shore, Staff Master Printer

“Sometimes, I approach a blank canvas with only a vague idea of how I will approach my subject matter. My process begins in different ways. Sometimes I’ll spend time in my studio just reading and looking at the work of various artists, and other times I’ll find an image in the real world that inspires me to begin a painting. Everything is a potential source for an idea for a painting subject; photographs I’ve taken or magazine photos, as well as sketches directly from nature. I work reactively, working on one area and seeing how that relates to another area of the canvas and how it needs to work as a whole, in terms, of rhythm, form, and color.”

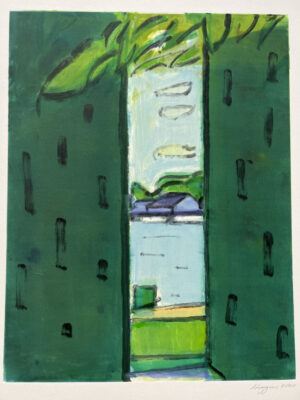

“The window is a motif that I often use to frame both interior and exterior spaces, as well as “how the light gets in.” I have no preconceived notion of how a painting should be; I have no ultimate plan. It’s the challenge and sense of surprise that interests me…otherwise, I would be bored. The process would become too formulaic. “

“I’m trying to get to the “essence” of things in my work. I prefer to avoid everything being literally spelled out for the viewer. I want the viewer to be brought to my attention and moved by my work.”

“I am a messy painter; I don’t have a clean, organized studio or palette. I work in a very reactive, intuitive way. I start by making marks of thinned-out oil paint on the canvas. Sometimes with a colored ground and other times work directly on a white canvas – it depends.”

“Working on a new canvas is always exciting to me –and then almost immediately, I think, OK, what am I doing, and how do I resolve this? How do I achieve the sense of light, space, mood, and poetry I’m after? Sometimes it comes easily, sometimes, it doesn’t, and sometimes if it’s not working, I put the painting aside and try not to get dejected. It’s a love/hate thing for me. Sometimes I’ll come back to it, and sometimes, I can resolve it. I’ve learned that often I will eventually, but not always, be able to make it work. So in that sense, making a good painting is a process, a practice, something you work at. I’ve realized that I can’t just go into my studio and expect to create a great painting every time.”

“On the contrary, sometimes these paintings only resolve after putting in a lot of time, energy, and struggle. Often I have to pull it apart, wipe it down and start over, losing all the good parts with the bad. However, when I do get into that very focused Zen-like state of concentration where everything seems to be working – it’s a great feeling. Would I call this “obsessive”? I’m not “obsessing” over resolving the painting I made. Instead, I continue to explore new and different ways to finish, which may turn out to be a very different painting than it started out to be.”

I asked Elizabeth what artists or paintings have been most influential to her.

She admitted this was difficult to answer as there are so many artists and reasons why they might be important to her. Braque, Gaugin, Degas, Balthus and Morandi but more than anything, the post-impressionists, such as Bonnard, Vuillard, and the painter with the most lasting and essential influence, were Matisse and his approach to simplification and his use of color who said:

“I have always tried to hide my own efforts and wanted my work to have the lightness and joyousness of a springtime which never anyone suspect the labors has cost me.”

She also noted that Matisse said:

“A young painter who cannot liberate himself from the influence of past generations is digging his own grave.”

“I’ve been attracted to Matisse’s color for a long time. I remember seeing the 2010 show at MoMA: “Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913-1917. I particularly loved his paintings “Interior With A Goldfish Bowl”, “Goldfish and Palette” and “The Piano Lesson .” I admire many aspects, but what particularly strikes me is his sophistication in using dark blacks and greys to frame areas of flattened planes of color. The vibrance of his color harmonies and use of the window as a motif to reflect both the interior and exterior worlds are all things I get excited about.”

Hans Hofmann’s teaching about color was formative in many of Higgins’s teachers, especially Robert de Niro, Sr., who was another important influence on her. This aesthetic is apparent in her work.

Hofmann said, “Whether you use it in a decorative sense or in the sense of a grand symphonic poem, the import thing always to be remembered is that the chief function of color is to create light.” “In nature, light creates the color; in the picture, color creates light.” A great book to read on Hofmann’s teaching is the 2011 book; Color Creates Light: Studies with Hans Hofmann by Tina Dickey. She talks at length about his teachings, especially how he taught that pictorial light mainly comes from the degrees of color contrast, such as light against dark or warm against cool. Hofmann suggests that color as light doesn’t come from naturalistic tonal gradations; instead, it’s the pure, unbroken color planes reacting to adjacent colors and their degrees of contrast. The painter’s choices on how one color shape sits next to another evoke more of the sensation of light.

In response to my asking to hear more about her approach to painting her motifs, she replied,

“I try to avoid drowning out the beauty of the natural order of things.. I want to be respectful of nature’s narrative and express my emotional response to what I see around me by emphasizing the recurring elements of light, shapes, and colors, which tell a compelling story and celebrate the real world.”

“As far as the subject matter is concerned, my art has broadened to include my children in my figurative work. Besides bringing light into my life, my children, I know, have found a way into my art.

For many years, I didn’t have the time to focus on my art while raising four young children, and when they reached high school, my role as a mother became more demanding. Being committed to both my art and my young family wasn’t possible for me. To be a good mother, something had to give. It was my art. As my children have grown up, I now have more time to dedicate to my art. I wouldn’t have done it any other way.”

“In the later stages of my life, marriage, motherhood, and the loss of my son, my work has continued to be impacted and changed by a whole new set of experiences and challenges that I could never have imagined as a college or graduate student.”

“The impact of my cumulative experiences over years of marriage, motherhood, and tragedy shapes my art today. I would say that my art today is a mixture of the expressionism of my early work, the formal training of my MFA, and the everyday involvement in all aspects of family life.”

I asked Elizabeth if her paintings ever had a spiritual component, and she answered by saying,

“No, not intentionally. But all art is, in a way, spiritual.

Gerhard Richter once said, “Art is the highest form of hope.” His words certainly ring true for many who have suffered a loss. I believe in the power of art and how the experience of simply looking at art, listening to music, and reading a book, gives one a feeling of joy, comfort, a sense of solace, and hope.

Milton Glaser also said, “the urge to make things, to make art is probably a survival device; the urge to create beauty is something else.“

Glaser’s words resonate with me, having lost my only son. I didn’t know how to move forward at first, but after a point, I returned to my studio and eventually started making paintings and prints again. It was my way to survive. The simple act of making art, because it requires your full attention, was, in the Buddhist sense, a way for me to be fully present in this new world without my son.

Because the act of looking at art requires your full attention, in that way, it is spiritual. A friend of mine who is not an artist describes my work as being soulful – I asked her what she meant by that, and she said that it “moved” her and had gravitas. Does that mean it is also spiritual? Maybe.”

All proceeds from sales during her upcoming Prince Street Gallery exhibition will be donated to www.shatterproof.org in memory of her son, William Jones (1991 -2018).

Link to interview on the Zeuxis website Artisthood & Parenthood, an interview with Elizabeth Higgins & Clara Shen by Neil Plotkin

Elizabeth Higgins Website: elizabethhigginsartist.com

Elizabeth Higgins Instagram: @elizabethhigginsart

Love these paintings and so pleased to be introduced to the work of this brilliant artist. Thank you, Larry!